CS302 计算机操作系统

Lec01. Intro

Before this course (about)

- Have basic concept about Computer Organization

- Be familiar to at least one programming language (better be

C / C++) - We use

Rustas example code in this course- Learning Rust : https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/book

- Search for OSTD

libandmod: https://docs.rs/ostd/latest/ostd/

Definitions of OS

What is a computer ?

How does a modern computer work ?

What is operating systems ?

- Structure of a Computer System (4 parts)

- Hardware

- Provides basic computing resources

- CPU, memory, I/O devices

- Operating system

- Controls and coordinates use of hardware among various applications and users

- Application programs

- Define the ways in which the system resources are used to solve the computing problems of the users

- Word processors, compilers, web browsers, database systems, video games

- Users

- People, machines, other computers

- Hardware

Def. OS is a group of software that makes the computer operate correctly and efficiently in an easy-to-use manner.

- Execute user programs and make solving user problems easier

- Make the computer system convenient to use

- Use the computer hardware in an efficient manner (hardware abstraction)

ask again: what is an OS ?

- It includes a software program called kernel

- manages all the physical devices (e.g., CPU, RAM and hard disk)

- exposes some functions such as system calls for others to configure the kernel or build software (e.g., C library) on top

- It includes other “helper” programs

- Such as a shell, which renders a simple command-line user interface with a full set of commands

- Such as a GUI (graphic user interface), which renders a user friendly interface with icons representing files and folders

- Such as a Browser, which helps the user to visit websites

ask again and again: what is an OS ?

- An OS is a resource manager

- Managing CPUs, memory, disks, I/O devices (keyboards, USB drive, sensors, …)

- Arbitrator of conflicting requests for efficient and fair resource use

- An OS is a control program

- Controls execution of programs to prevent errors and improper use of the computer

SHORT SUMMARY

There is no exact definition about Operating System. It can have so many functions and computer depends on it so much.

It’s like a bridge between users and hardware, between applications and hardware. All of the modern computer cannot live without Operating Systems.But what an OS actually do ?

What does an Operating Systems do ?

- Virtualization (虚拟化)

- Virtualize CPU: Run multiple programs on a single CPU (as if there are many CPUs)

- Virtualize memory: Give each process (or programs if you will) the illusion of running in its own memory address space

- Concurrency (并发性)

- Run multi-threaded programs and make sure they execute correctly

- Persistence (持久性)

- Write data (from volatile SRAM/DRAM) into persistent storage

- Performance, crash-resilience

- etc.

Organzied by the functionalities of OS (three easy pieces)

- Virtualization (Process, scheduling, memory address space, swapping)

- Concurrency (Threads, locks, semaphores)

- Persistence (I/O, storage, file systems)

OS Concepts

Process (进程)

Def. A process is a program in execution. (Program is a passive entity and process is an active entity.)

Properties

- Process needs resources to accomplish its task

- CPU, memory, I/O, files

- Process termination requires reclaim of any reusable resources

- Process executes instructions sequentially, one at a time, until completion

- Single-threaded process has one program counter specifying location of next instruction to execute

- Multi-threaded process has one program counter per thread

- Typically, system has many processes, some user, some operating system running concurrently on one or more CPUs

- Concurrency by multiplexing the CPUs among the processes / threads

Process Management

- Creating and deleting both user and system processes

- Suspending and resuming processes

- Providing mechanisms for process synchronization

- Providing mechanisms for process communication

- Providing mechanisms for deadlock handling

Memory

- DRAM (Dynamic Random Access Memory) is the main memory used for all desktop, laptops, servers, and mobile devices

- CPU only directly interacts with the main memory during execution

- All data in memory before and after processing

- All instructions in memory in order to execute

- OS manages the main memory for kernel and processes

- OS dictates which process can access which memory regio

Memory Management

- Memory management determines what is in memory when

- Optimizing CPU utilization and computer response to users

- Memory management activities

- Keeping track of which parts of memory are currently being used and by whom

- Deciding which processes (or parts thereof) and data to move into and out of memory

- Allocating and deallocating memory space as needed

File System & I/O

- File-System management

- Files usually organized into directories

- Access control on most systems to determine who can access what

- OS activities include

- Creating and deleting files and directories

- Primitives to manipulate files and dirs

- Mapping files onto secondary storage

- Backup files onto stable (non-volatile) storage media

- I/O Subsystem

- One purpose of OS is to hide peculiarities of hardware devices from the user

- I/O subsystem responsible for

- Memory management of I/O including

- buffering (storing data temporarily while it is being transferred)

- caching (storing parts of data in faster storage for performance)

- General device-driver interface

- Drivers for specific hardware devices

- Memory management of I/O including

Protection and Security

- Protection 👉 any mechanism for controlling access of processes or users to resources defined by the OS

- Security 👉 defense of the system against internal and external attacks

- Huge range, including denial-of-service (DoS), worms (蠕虫), viruses, identity theft, theft of service

Lec02. OS Basics

Outline

- Dual-mode operations

- Kernel structure

- Operating system services

Dual-Mode Operations

Overview

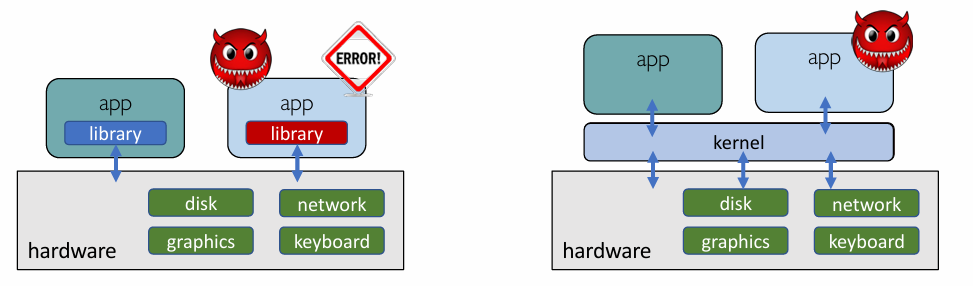

- Evolution of OS

- A library to handle low-level I/O

- Issue: Fault and security isolation

- Kernel: A bigger “library” to handle low-level I/O

- Kernel needs to be protected from faulty/malicious apps

- A library to handle low-level I/O

- Application code runs in User mode

- Kernel code runs in Kernel mode

- Dual-mode operation allows OS to protect itself and other system components (attack from app can be handle by kernel)

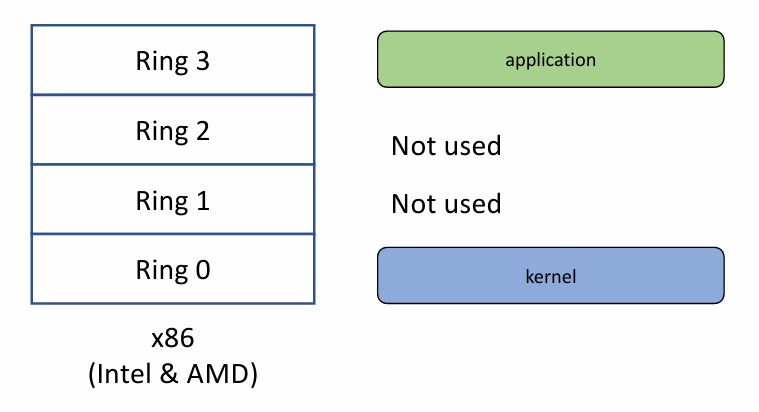

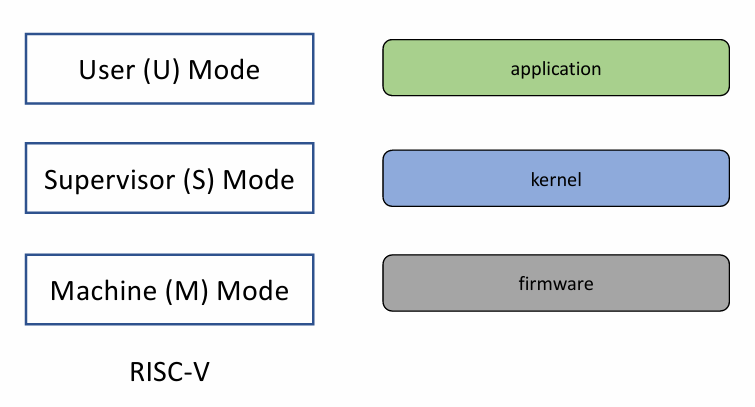

- Question: What is needed in the hardware to support “dual mode” operation?

- A bit for representing current mode (user/kernel mode bit)

- Certain operations / actions only permitted in kernel mode (in user mode they fail or trap)

- { User 👉 Kernel } transition sets kernel mode AND saves the user PC

- Operating system code carefully puts aside user state then performs the necessary operations

- { Kernel 👉 User } transition clears kernel mode AND restores appropriate user PC

Mode bits on different architectures 👇

|

|

Mode Transitions

Three types :

- System call

- Process requests a system service, e.g.,

exit - Like a function call, but

“outside” the process - Does not have the address of the system function to call

- Marshall (排序?) the syscall id and args in registers and exec syscall

- Process requests a system service, e.g.,

- Interrupt

- External asynchronous event triggers context switch

- e. g., Timer, I/O device

- Independent of user process

- Trap or Exception

- Internal synchronous event in process triggers context switch

- e.g., Protection violation (segmentation fault), Divide by zero, …

System Calls

Def. Programming interface to the services provided by the OS, typically written in a high-level language (C or C++).

中文解释:系统调用是一个用高级程序语言定义的,调用操作系统提供的服务的程序接口。

Implementation

- Typically, a number associated with each system call

- System-call interface maintains a table indexed according to these numbers

- The system call interface invokes intended system call in OS kernel and returns status of the system call and any return values (a basic example below)

- The caller needs to know nothing about how the system call is implemented

- Just needs to obey calling convention and understand what OS will do

- Most details of OS interface hidden from programmer by library API

- Managed by run-time support library (set of functions built into libraries included with compiler)

1 |

|

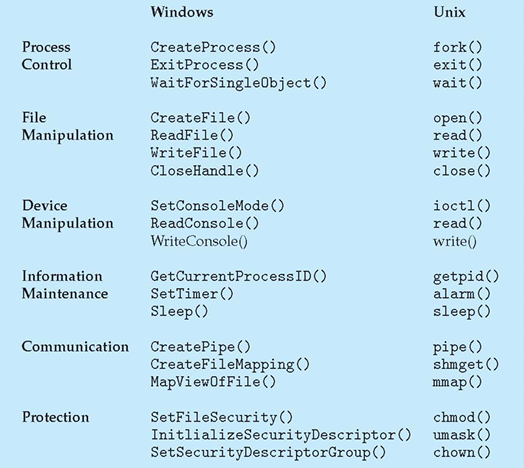

- Types of Syscalls

Exception and Interrupt

- Exceptions (synchronous) react to an abnormal condition

- E.g., Map the swapped-out page back to memory

- Divide by zero

- Illegal memory accesses

- Interrupts (asynchronous) preempt normal execution

- Notification from device (e.g., new packets, disk I/O completed)

- Preemptive scheduling (e.g., timer ticks)

- Notification from another CPU (i.e., Inter-processor Interrupts)

- More about (in the same procedure)

- Stop execution of the current program

- Start execution of a handler

- Processor accesses the handler through an entry in the

Interrupt Descriptor Table (IDT) - Each interrupt is defined by a number

Kernel Structure

Intro

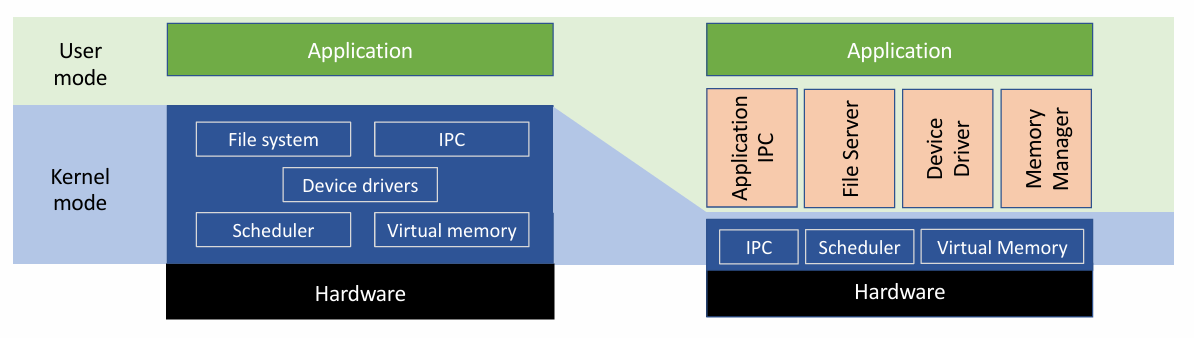

I. Monolithic Kernel

- A monolithic kernel is an operating system software framework that holds all privileges to access I/O devices, memory, hardware interrupts and the CPU stack.

- Monolithic kernels contain many components, such as memory subsystems and I/O subsystems, and are usually very large.

- Including filesystems, device drivers, etc.

- Monolithic kernel is the basis for Linux, Unix, MS-DOS.

II. Micro Kernel

- Microkernels outsource the traditional operating system functionality to ordinary user processes for better flexibility, security, and fault tolerance.

- OS functionalities are pushed to user-level servers (e.g., user-level memory manager)

- User-level servers are trusted by the kernel (often run as root)

- Protection mechanisms stay in kernel while resource management policies go to the user-level servers

- Representative micro-kernel OS

- Mach, 1980s at CMU

- seL4, the first formally verified micro-kernel, more on http://sel4.systems

Pros and Cons

- Pros

- Kernel is more responsive (kernel functions in preemptible user-level processes)

- Better stability and security (less code in kernel)

- Better support of concurrency and distributed OS (later……)

- Cons

- More IPC needed and thus more context switches (slower)

III. Hybrid Kernel

- A combination of a monolithic kernel and a micro kernel

- Example: Windows OS

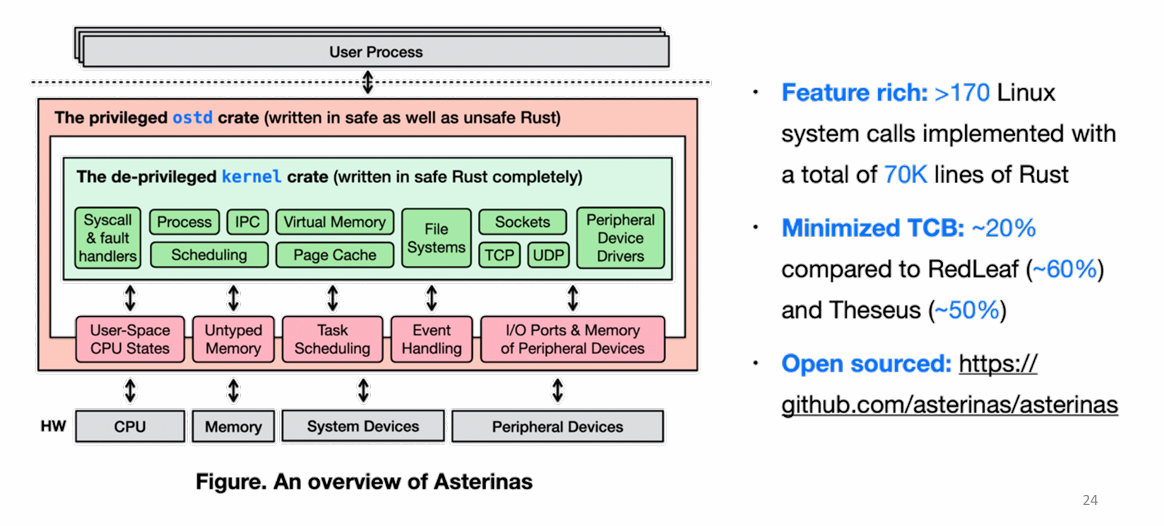

IV. FrameKernel: Asterinas

OS Design Principles

- Internal structure of different Operating Systems can vary widely

- Start by defining goals and specifications

- Affected by choice of hardware, type of system

- User goals and System goals

- User goals 👉 operating system should be convenient to use, easy to learn, reliable, safe, and fast

- System goals 👉 operating system should be easy to design, implement, and maintain, as well as flexible, reliable, error-free, and efficient

- OS separates policies and mechanisms

- Policy: which software could access which resource at what time

- E.g., if two processes access the same device at the same time, which one goes first

- E.g., if a process hopes to read from keyboard

- Mechanism: How is the policy enforced

- E.g., request queues for devices, running queues for CPUs

- E.g., access control list for files, devices, etc.

- The separation of policy from mechanism is a very important principle, it allows maximum flexibility if policy decisions are to be changed later

- Policy: which software could access which resource at what time

Operating System Services

I. User-helpful OS services

- User interface - Almost all operating systems have a user interface (UI)

- Varies between Command-Line (CLI), Graphics User Interface (GUI), Batch

- Program execution - The system must be able to load a program into memory and to run that program, end execution, either normally or abnormally (indicating error)

- I/O operations - A running program may require I/O, which may involve a file or an I/O device

- File-system manipulation - The file system is of particular interest. Obviously, programs need to read and write files and directories, create and delete them, search them, list file Information, permission management

- Communications – Processes may exchange information, on the same computer or between computers over a network

- Communications may be via shared memory or through message passing (packets moved by the OS)

- Error detection – OS needs to be constantly aware of possible errors

- May occur in the CPU and memory hardware, in I/O devices, in user program

- For each type of error, OS should take the appropriate action to ensure correct and consistent computing

- Debugging facilities can greatly enhance the user’s and programmer’s abilities to efficiently use the system

II. User Operating System Interface

- Command Line Interface (CLI) or command interpreter allows direct command entry

- User-friendly desktop metaphor interface

- e.g. mouse, keyboard and monitor. Icons of app.

- Many systems now include both CLI and GUI interfaces

III. System Programs

- Provide a convenient environment for program development and execution

- Most users’ view of the operation system is defined by system programs

- File management

- Status Info

- Programming-language support 👉 Compilers, assemblers, debuggers and interpreters sometimes provided

- Program loading and execution

- Communications 👉 Provide the mechanism for creating virtual connections among processes, users, and computer systems

Lec03. Process

Outline

- Process and system calls

- Process creation

- Kernel view of processes

- Kernel view of

fork(),exec(), andwait() - More about processes

Process and System Calls

What’s a process ?

- Process is a program in execution

- A program is a file on the disk

- Code and static data

- A process is loaded by the OS

- Code and static data are loaded from the program

- Heap and stack are created by the OS

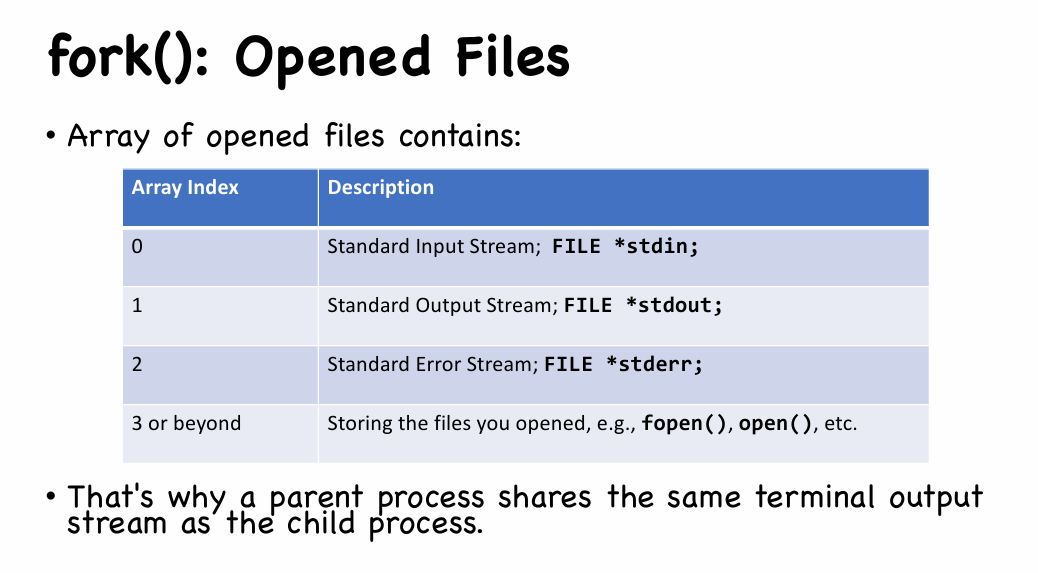

- A process is an abstraction of machine states

- Memory: address space

- Register:

- Program Counter (PC) or Instruction Pointer

- Stack pointer

- frame pointer

- I/O: all files opened by the process

Seems that definitions of process are multiple, there is only one way to get unique process.

1 | int main(void) { |

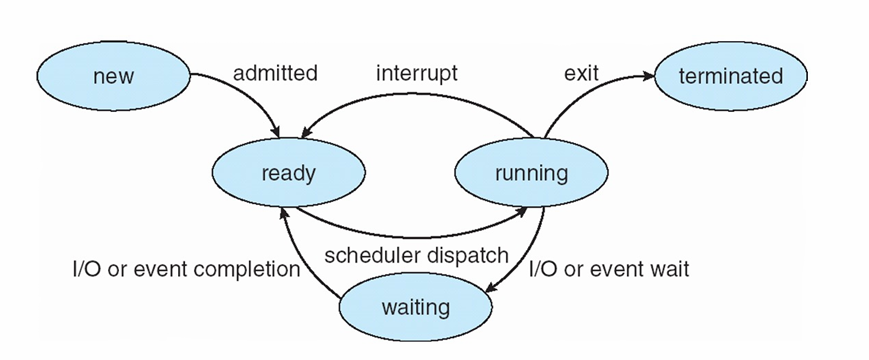

Process Life Cycle

What’s System calls ?

- System call is a function call.

- exposed by the kernel.

- abstraction of kernel operations.

- System call is a call by number

- System call sometimes need extra parameter. Three ways to pass param.

- Registers: pass the parameters in registers

- In some cases, may be more parameters than registers

x86andrisc-vtake this approach

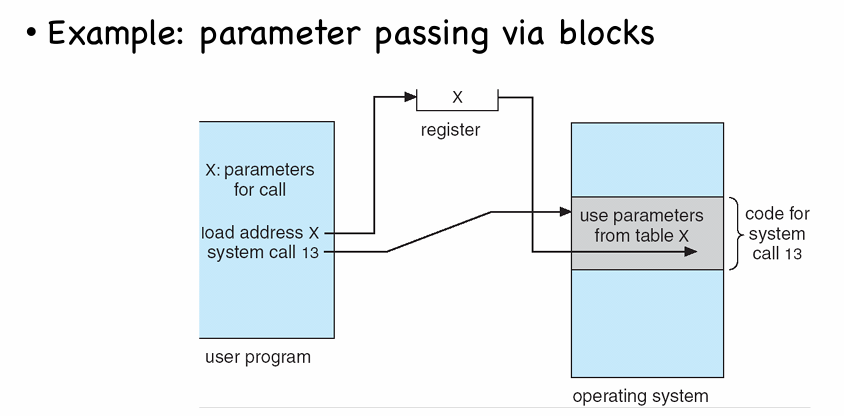

- Blocks: Parameters stored in a memory block and address of the block passed as a parameter in a register (e.g. pic below)

- Stack: Parameters placed, or pushed, onto the stack by the program and popped off the stack by the operating system

- Block and stack methods do not limit the number or length of parameters being passed

- Registers: pass the parameters in registers

System Call v.s. Library API Call

Test:

| Name | System call ? |

|---|---|

printf() & scanf() |

No |

malloc() & free() |

NO |

fopen() & fclose() |

No |

mkdir() & rmdir() |

Yes |

chown() & chmod() |

Yes |

- E.g.

fopen()fopen()invokes the system callopen().open()is too primitive and is not programmer-friendly!

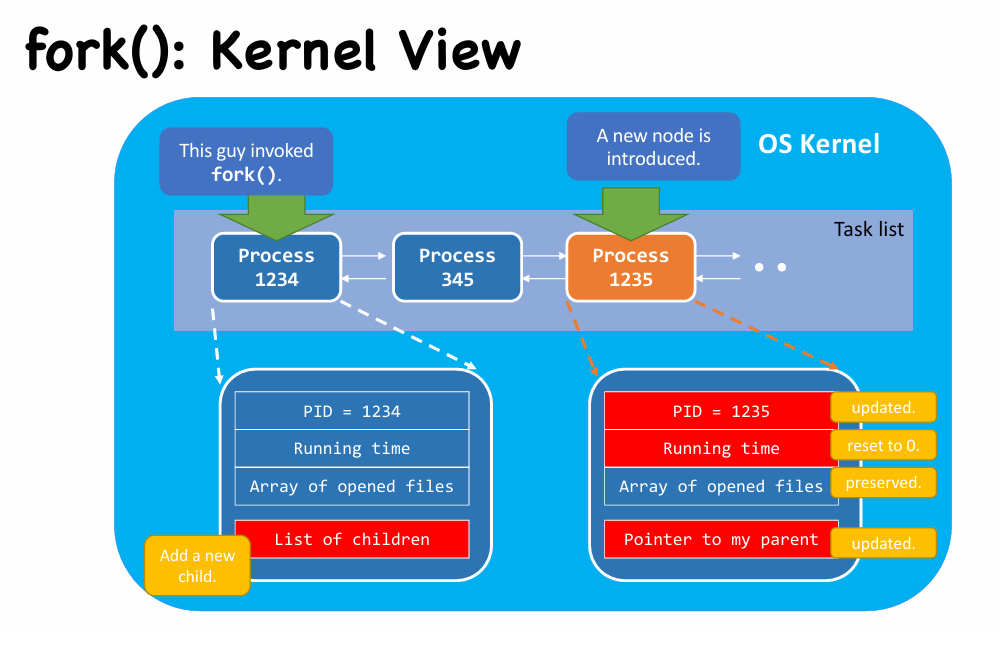

Process Creation

fork()

- Parent process create children processes. (form tree structure)

- use

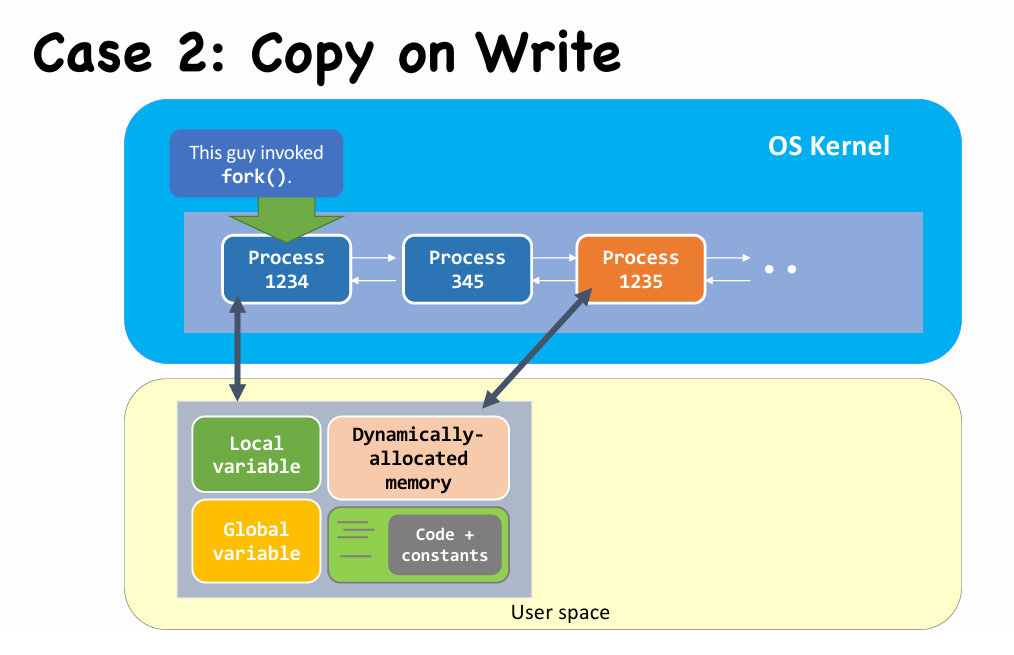

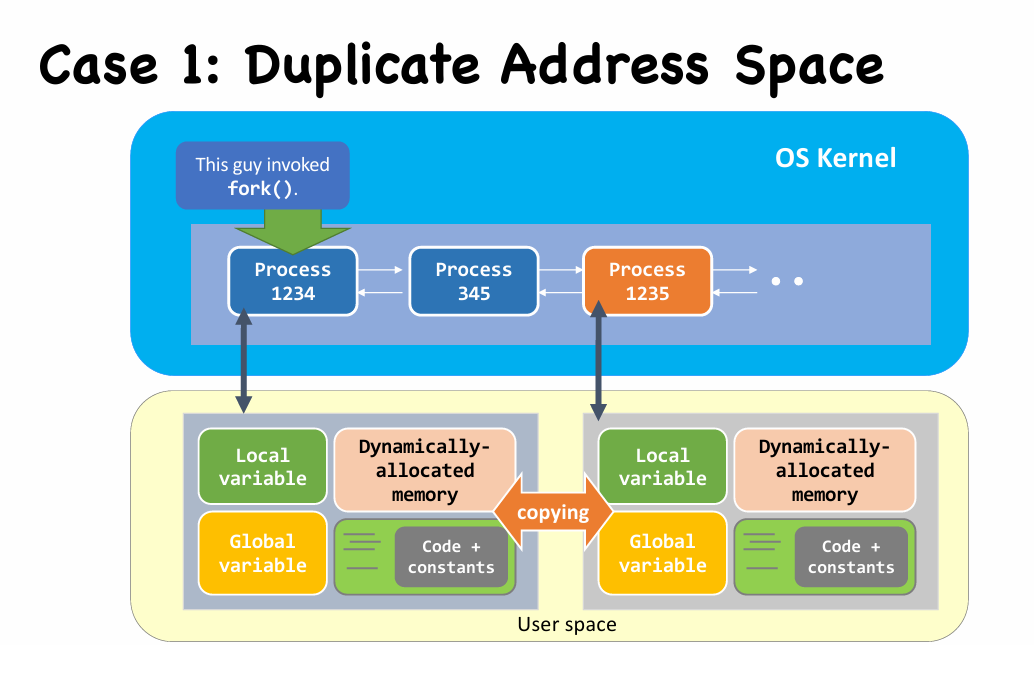

pidto identify a process - Address space

- Child duplicate of parent

- Child has a program loaded into it

- UNIX examples

fork()system call creates new processexec()system call used after a fork to replace the process’ memory space with a new program

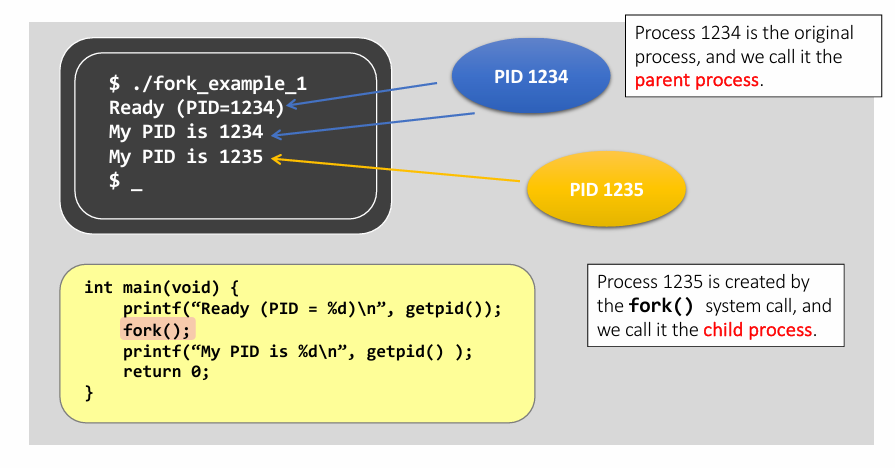

- View on example : 👆

- Both the parent and the child execute the same program.

- The child process starts its execution at the location that

fork()is returned, not from the beginning of the program.

- Another example below :

1 | int main(void) { |

- Suppose parent’s pid is 1234. Then the

fork()create a child process with pid 1235. fork()returns value for both parent and child process. See how they differ in value.- CPU decides which process run first.

1 | # if child run first: |

fork()behaves like “cell division”.- It creates the child process by cloning from the parent process, including all user-space data

| Cloned items | Description |

|---|---|

| Program counter [CPU register] |

That’s why they both execute from the same line of code after fork() returns. |

| Program code [File & Memory] |

They are sharing the same piece of code. |

| Memory | Including local variables, global variables, and dynamically allocated memory. |

| Opened files [Kernel’s internal] |

If the parent has opened a file “fd”, then the child will also have file “fd” opened automatically. |

-

- also something distinct:

| Distinct items | Parent | Child |

|---|---|---|

Return value of fork() |

PID of child | 0 |

| PID | unchanged | new pid(not necessarily parent’s +1) |

| Parent process | unchanged | Parent. |

| Running time | Cumulated | Just created, should be 0 |

| [Advanced]File locks | unchanged | None |

exec()

If a process can only duplicate itself and always runs the same program, it’s not meaningful. How can we execute other programs ?

Answer: using

exec()system call !

1 | int main(void) { |

1 | # Output |

- Detail about

exec() - Run the command

/bin/ls

| Argument Order | Value in example | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “/bin/ls” | The file that the programmer wants to execute. |

| 2 | “/bin/ls” | When the process switches to “/bin/ls”, this string is the program argument[0]. |

| 3 | NULL | This states the end of the program argument list. |

- E.g. run the command

/bin/ls -l- C code:

execl("/bin/ls", "/bin/ls", "-l", NULL);

- C code:

Q: Why the origin program ends ? (No “after execl…” printed)

A: The program in the address space has been changed.

解释:

exec_example程序调用execl()系统调用后,该进程的地址空间存储代码的部分会切换成execl中参数指定的程序,而该程序运行结束后不会切换回原来的程序代码,所以进程结束。

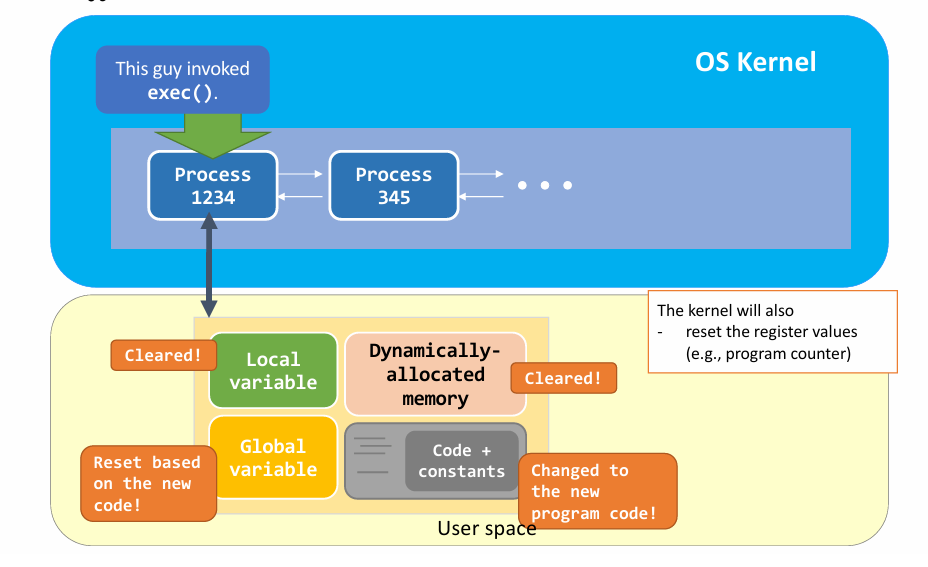

Summary

- The process is changing the code that is executing and never returns to the original code.

- The last two lines of codes are therefore not executed.

- The process that calls an

execsystem call will replace user space info, e.g.,- Program Code

- Memory: local variables, global variables, and dynamically allocated memory;

- Register value: e.g., the program counter;

- But, the kernel-space info of that process is preserved, including:

- PID;

- Process relationship;

- etc.

wait()

Recall: previous exmaple with syscall

wait().

1 | int main(void) { |

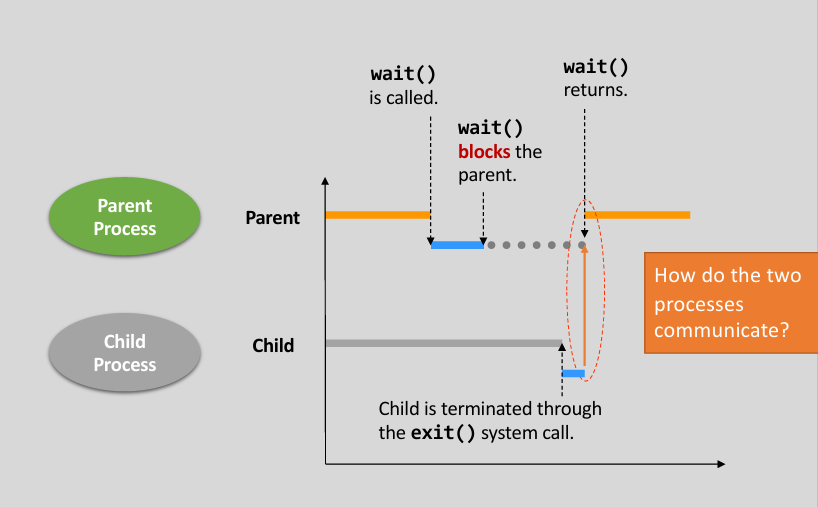

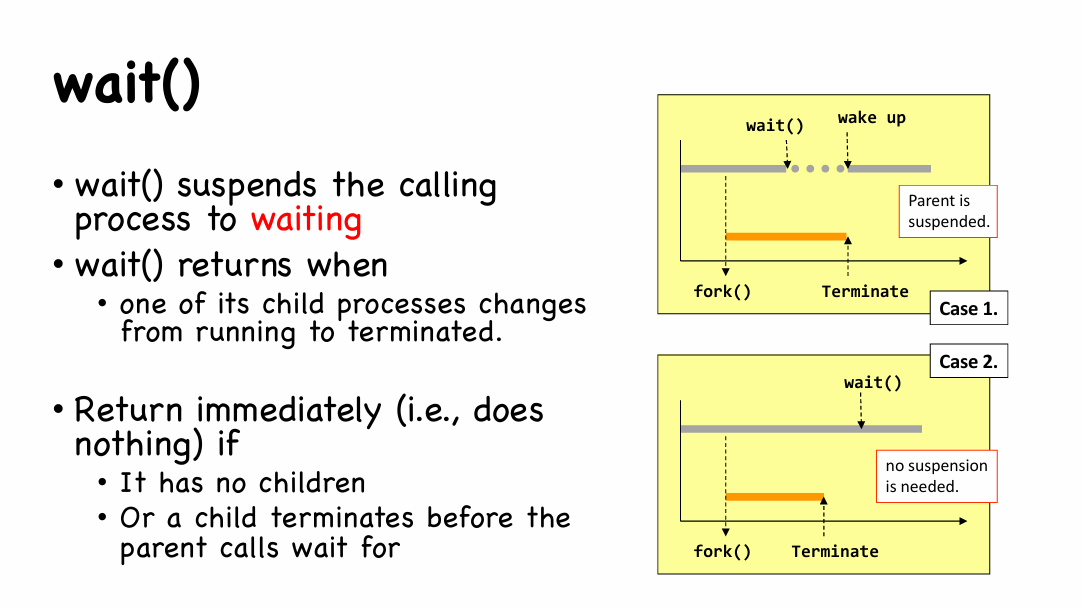

wait()called at parent process 👉 if the CPU schedules parent process to run first, then it will wait until child process finished.(like this 👇)

1 | $ ./fork_example |

wait()vs.waitpid()wait()- Wait for any one of the child processes

- Detect child termination only

waitpid()- Depending on the parameters, waitpid() will wait for a particular child only

- Depending on the parameters, waitpid() can detect different status changes of the child (resume/stop by a signal)

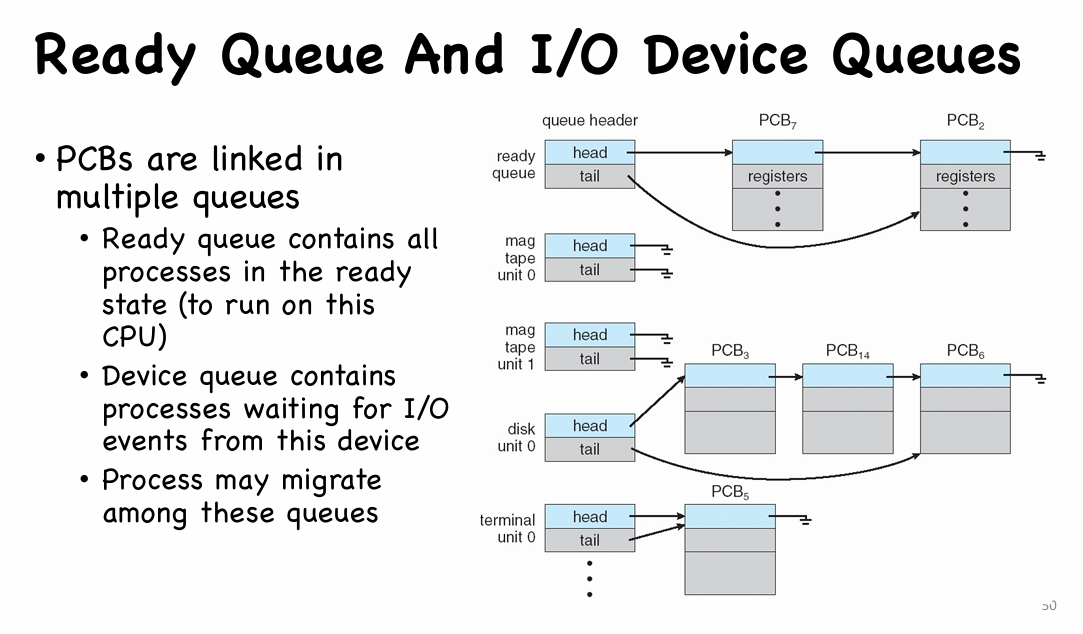

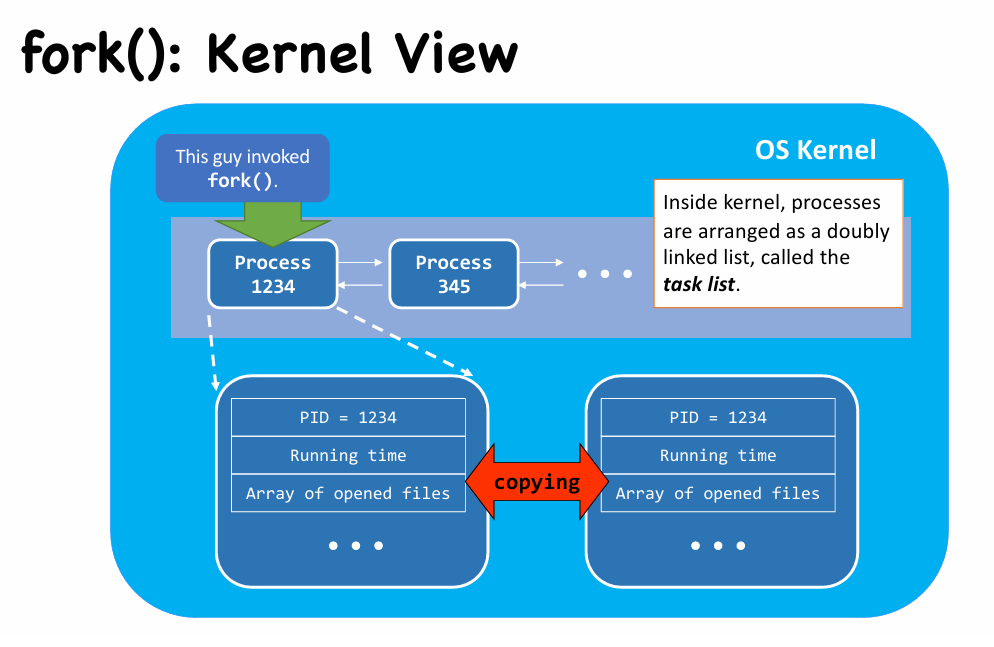

Kernel view of processes

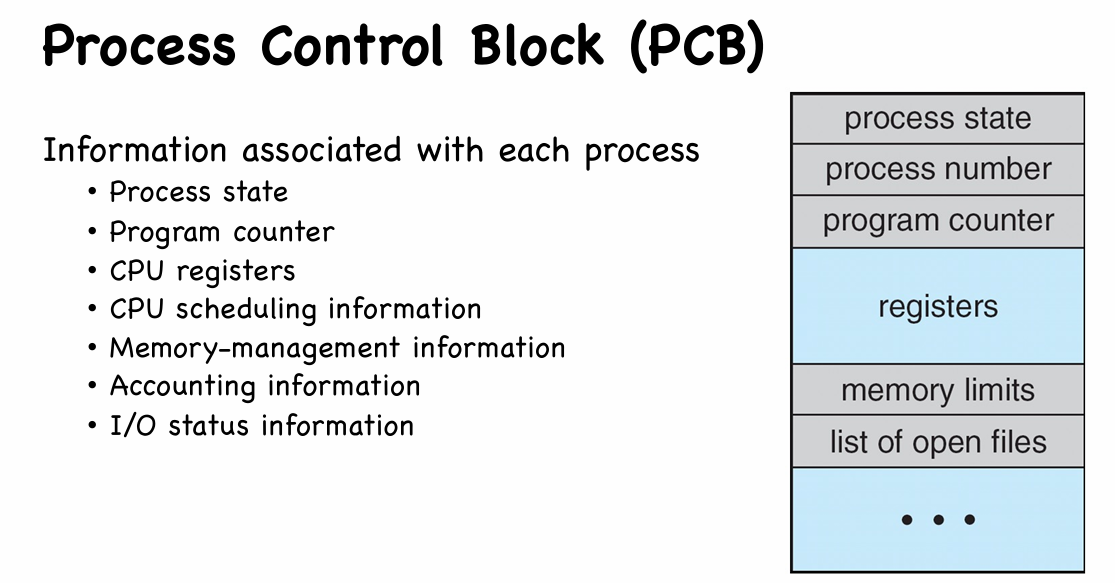

PCB

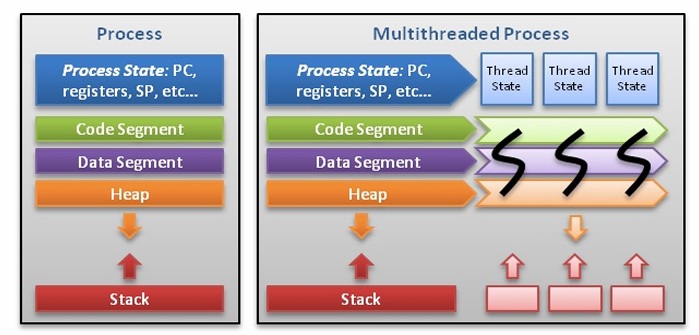

Process and Thread

- One process may have more than one threads (一个进程对多个线程)

- A single-threaded process performs a single thread of execution

- A multi-threaded process performs multiple threads of execution “concurrently”, thus allowing short response time to user’s input even when the main thread is busy

- PCB is extended to include information about each thread

单线程进程 vs. 多线程进程 👇

Context Switch

- Once a process runs on a CPU, it only gives back the control of a CPU

- when it makes a system call

- when it raises an exception

- when an interrupt occurs

- What if none of these would happen for a long time?

- Coorperative scheduling: OS will have to wait

- Early Macintosh OS, old Alto system

- Non-coorperative scheduling: timer interrupts

- Modern operating systems

- Coorperative scheduling: OS will have to wait

- When OS kernel regains the control of CPU

- It first completes the task

- Serve system call, or

- Handle interrupt/exception

- It then decides which process to run next

- by asking its CPU scheduler (in later chapter)

- It performs a context switch if the soon-to-be-executing process is different from the previous one

- It first completes the task

About context switch

- During context switch, the system must save the state of the old process and load the saved state for the new process

- Context of a process is represented in the PCB

- The time used to do context switch is an overhead of the system; the system does no useful work while switching

- Time of context switch depends on hardware support

- Context switch cannot be too frequent

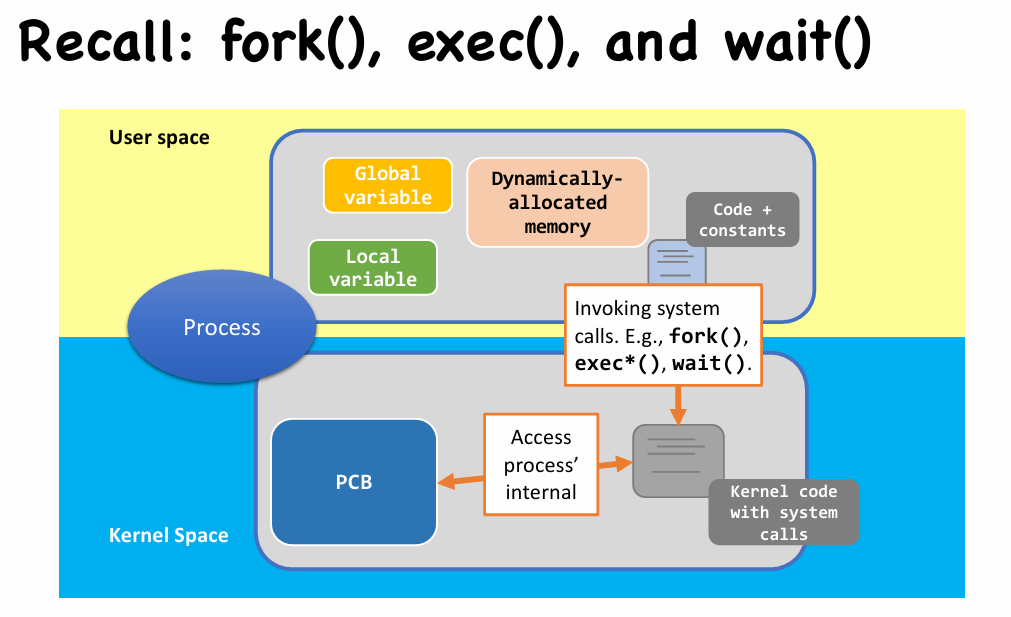

Kernel view of fork(), exec(), and wait() (❗Important)

Overview

fork(): Kernel View

|

|

|

|

- More inside

fork()(in kernel view) - After creating the child process(PCB) and allocating user space(Dup’ or CoW), CPU take control to decide which one run first

- Both processes store their return value in PCB, ready to return from

fork()

What if two processes, sharing the same opened file, write to that file together?

exec(): Kernel View

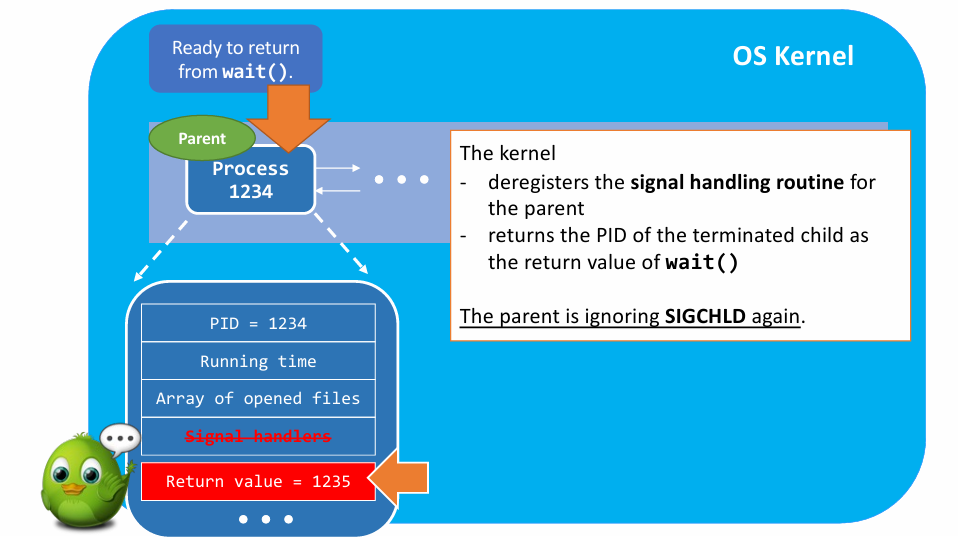

wait() and exit(): Kernel View

In user’s view :

exit()in kernel view :

|

|

|

|

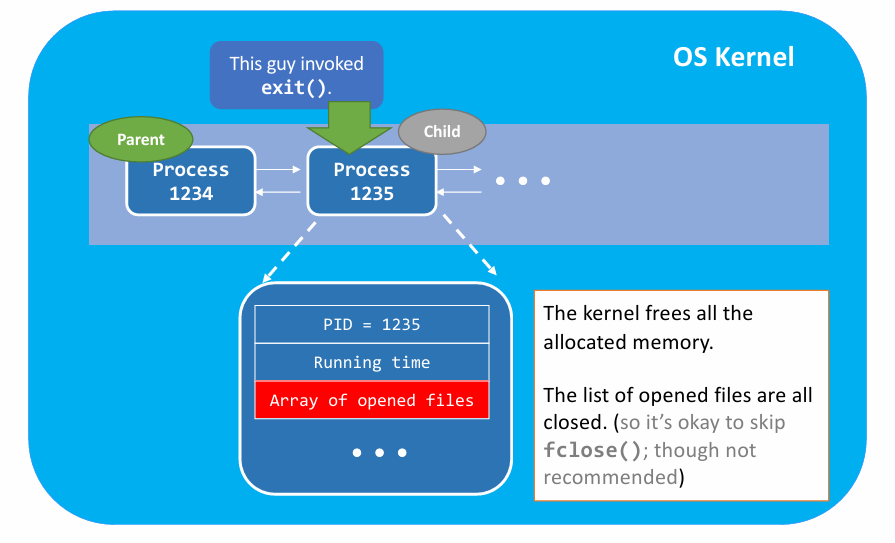

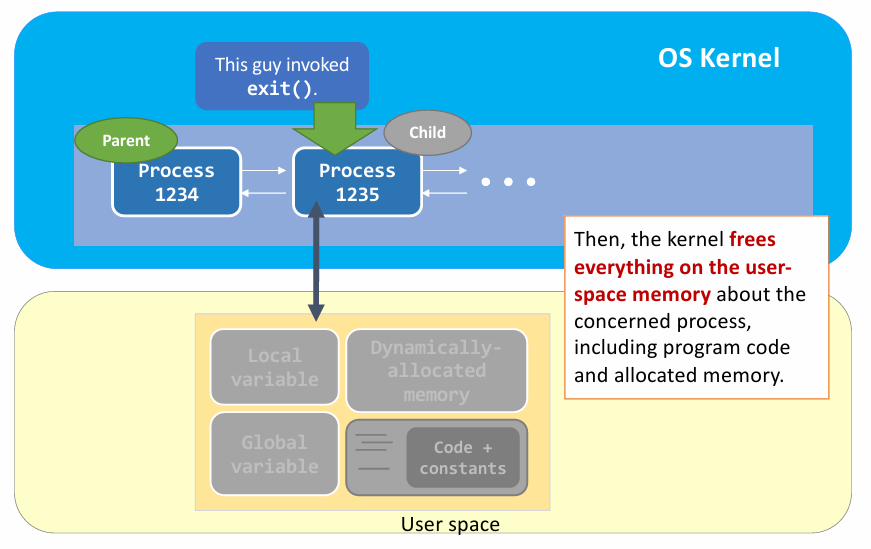

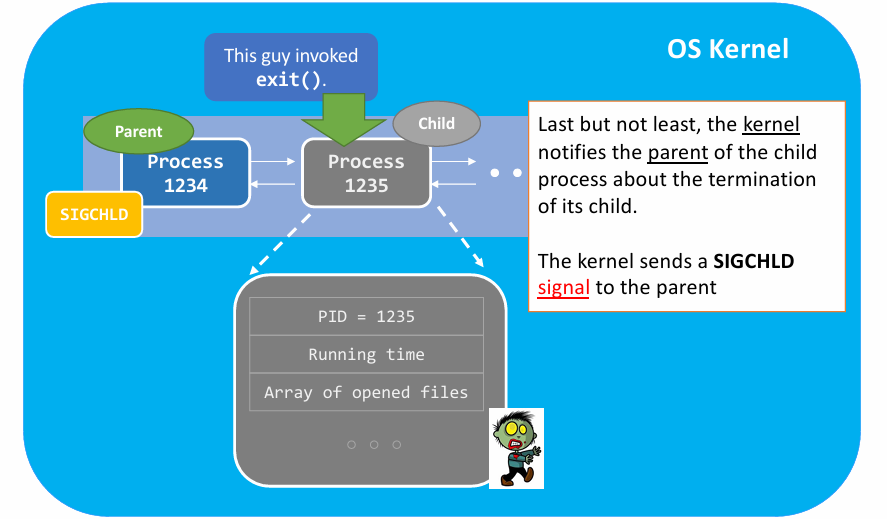

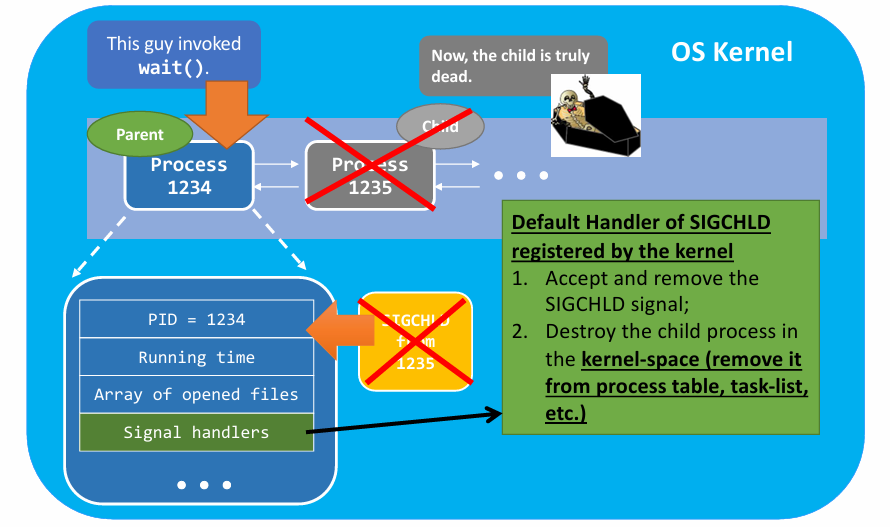

- Summary of

exit() - (1) Clean up most of the allocated kernel-space memory

- (2) Clean up the exit process’s user-space memory.

- (3) Notify the parent with

SIGCHLD.

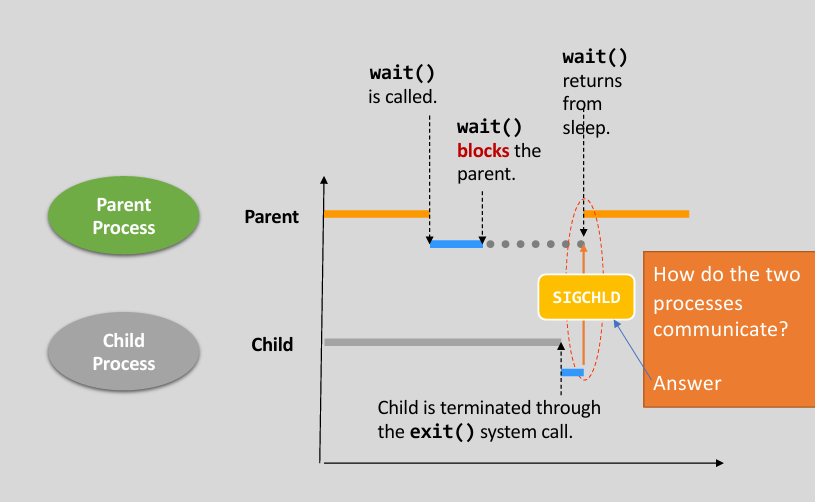

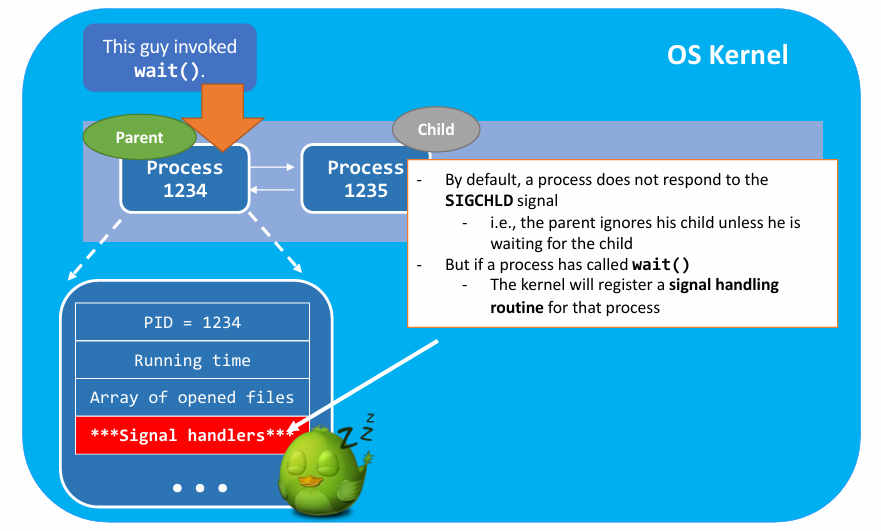

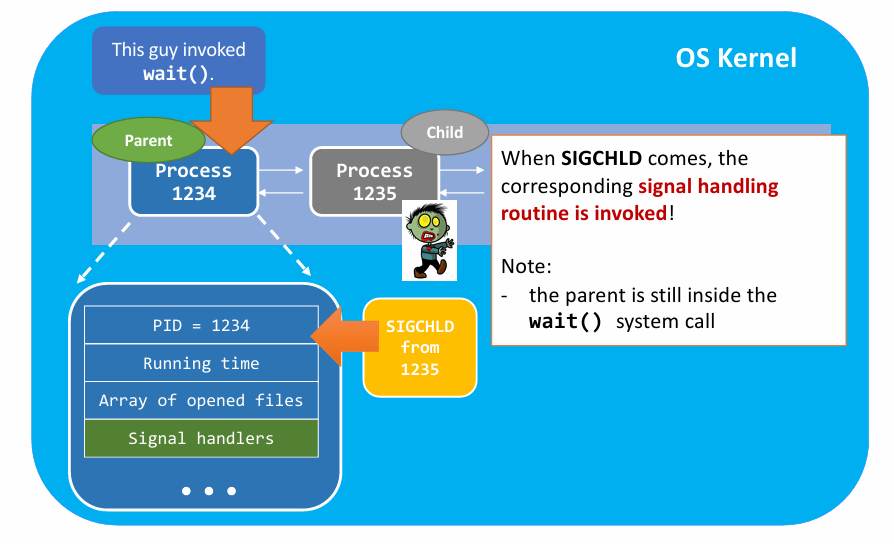

One problem: How do the two process communicate ? 👉 How does parent receive the signal ?

- Brief view on

wait()

|

|

|

|

(笔记不全)

-

Case Analysis

-

I. Normal case

- Parent call

wait(), and then child exit and sentSIGCHLD

- Parent call

-

II. Parent’s wait() after Child’s exit()

- This case is okay but the zombie wanders around until

wait()is called

- This case is okay but the zombie wanders around until

-

Using

wait()for Resource Management -

It is not only about process execution / suspension …

-

It is about system resource management.

- A zombie takes up a PID;

- The total number of PIDs are limited;

- Read the limit:

cat /proc/sys/kernel/pid_max - It is 32,768.

- Read the limit:

- What will happen if we don’t clean up the zombies? (maybe the computer cannot run any program.)

More about processes

The First Process

- We now focus on the process-related events.

- The kernel, while it is booting up, creates the first process –

init.

- The kernel, while it is booting up, creates the first process –

- The

initprocess:- has

PID = 1, and - is running the program code

/sbin/init.

- has

- Its first task is to create more processes …

- Using

fork()andexec().

- Using

A Tree of Process

- You can view the tree with the command:

pstree; orpstree –Afor ASCII-character-only display.

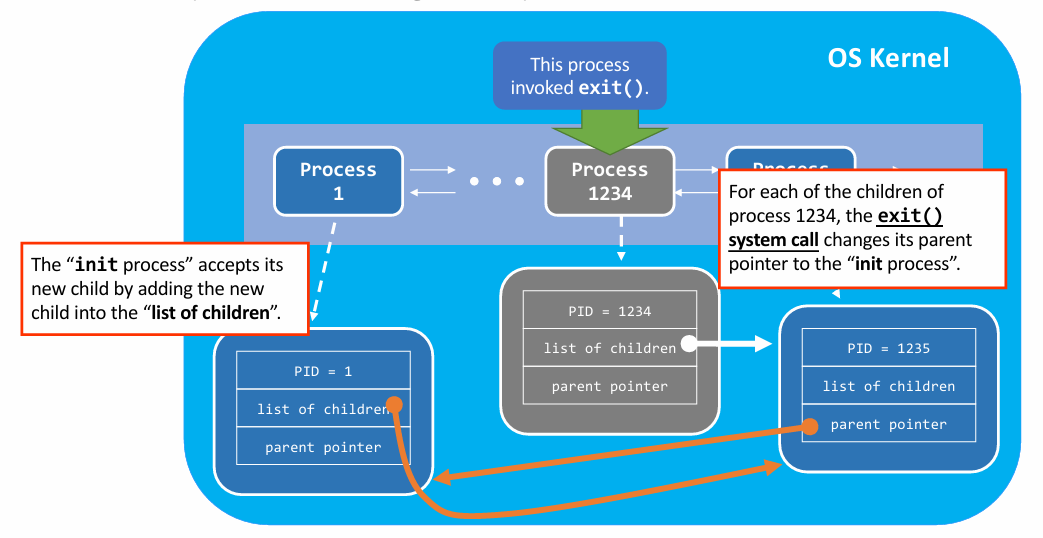

- Problem: What if a parent process (in the process tree) terminates before its children ?

- Answer: Using Re-parent

- In Linux

- The

initprocess will become the step-mother of all orphans - It’s called re-parenting

- The

- In Windows

- It maintains a forest-like process hierarchy

- Re-parent Explanation

- exitting parent change all the children’s parent pointer to init process

- Background Jobs

- The re-parenting operation enables something called background jobs in Linux

- It allows a process runs without a parent terminal/shell

Measure Process Time

Two aspect: User Time vs. System Time

Def. Real time: whole time to execute the program.

Def. User time: time to run a user’s code.

Def. System time: time to run a system’s code.

- The user time and the sys time together define the performance of an application.

- When writing a program, you must consider both the user time and the sys time.

- E.g., the output of the following two programs are exactly the same. But, their running time is not. (Pro 1 spend much more time to system call)

- When writing a program, you must consider both the user time and the sys time.

1 | // Pro 1 |

1 | // Pro 2 |

Lec04. CPU Scheduler

Outline

- Scheduler Concept

- Different Scheduling Algorithm

- Optimization

Scheduler Concept

- Scheduling is important when multiple processes wish to run on a single CPU

- CPU scheduler decides which process to run next

- Two types of processes

- CPU bound and I/O bound

| CPU bound | I/O bound | |

|---|---|---|

| Def | Spends most of its running time on the CPU, i.e., user-time -> sys-time |

Spends most of its running time on I/O, i.e., sys-time -> user-time |

| E.g. | AI course assignments. | /bin/ls, networking programs |

- CPU scheduler selects one of the processes that are ready to execute and allocates the CPU to it

- CPU scheduling decisions may take place when a process:

- Switches from running to waiting state

- Switches from running to ready state

- Switches from waiting to ready

- Terminates

Scheduling Algorithm Optimization Criteria

- Given a set of processes, with

- Arrival time: the time they arrive in the CPU ready queue (from waiting state or from new state)

- CPU requirement: their expected CPU burst time

- Minimize average turnaround time

- Turnaround time: The time between the arrival of the task and the time it is blocked or terminated.

- Minimize average waiting time

- Waiting time: The accumulated time that a task has waited in the ready queue.

- Reduce the number of context switches

Different Algorithm

Shortest Job First (SJF)

定义:字面意思

Type

- Non-preemptive

- Preemptive

- Non-preemptive SJF

- when new process arrive ready queue, the scheduler won’t step in immediately (until the current process blocked or terminated)

- when scheduler steps in, it selects next task based on remaining CPU requirement

- Preemptive SJF

- whenever a new process arrive ready queue, the scheduler steps in and selects the next task based on remaining CPU requirement

Round-robin (RR)

- Preemptive

- Every process given a quantum (the amount of time allowed to execute)

- when a process’s quantum used up, the process is preempted, placed at the end of the queue, with its quantum recharge

- then, the scheduler step in and choose the next process

- New process add to the tail of ready queue

- but won’t trigger a new selection decision

一个调度是否抢占,在 RR 中看的是触发调度时正在运行的进程是否已经执行完毕。

Priority scheduling

-

A priority number (integer) is associated with each process

-

The CPU is allocated to the process with the highest priority (smallest integer $equiv$ highest priority)

- Nonpreemptive: newly arrived process simply put into the queue

- Preemptive: if the priority of the newly arrived process is higher than priority of the currently running process, preempt the CPU

-

Static priority and dynamic priority

- static priority: fixed priority throughout its lifetime

- dynamic priority: priority changes over time

-

SJF is a priority scheduling where priority is the next CPU burst time

-

Problem: Starvation —— low priority process may never execute

-

Solution: Aging —— as time progresses increase the priority of the process

- 在等待队列待得越久,优先级越高,后续越容易被调度运行

Optimization: Completely Fair Scheduler

- Scheduling class

- Standard Linux kernel implements two scheduling classes

- (1) Default scheduling class: CFS

- (2) Real-time scheduling class

- Varying length scheduling quantum

- Traditional UNIX scheduling uses 90ms fixed scheduling quantum

- CFS assigns a proposition of CPU processing time to each task

- Nice value

- $-20$ to $+19$, default nice is 0

- Lower nice value indicates a higher relative priority

- Higher value is “being nice” (“够好了,不用这么多时间运行了”)

- Task with lower nice value receives higher proportion of CPU time

- Virtual run time

- Each task has a per-task variable vruntime

- Decay factor

- Lower priority has higher rate of decay

- nice = 0 virtual run time is identical to actual physical run time

- A task with nice $> 0$ runs for 200 milliseconds, its vruntime will be higher than 200 milliseconds

- A task with nice $\lt 0$ runs for 200 milliseconds, its vruntime will be lower than 200 milliseconds

- Lower virtual run time, higher priority

- To decide which task to run next, scheduler chooses the task that has the smallest vruntime value

- Higher priority can preempt lower priority

Example

- Example: Two tasks have the same nice value

- One task is I/O bound and the other is CPU bound

- vruntime of I/O bound will be shorter than vruntime of CPU bound

- I/O bound task will eventually have higher priority and preempt CPU-bound tasks whenever it is ready to run

Lec05. Synchronization

Outline

- Process Communications: Race Condition and Mutual Exclusion

- Solution Implementation: Critical Section

- Spin-based Lock

- Sleep-based Lock

Process Communications

- Threads of the same process share the same address space

- Global variables are shared by multiple threads

- Communication between threads made easy

- Process may also need to communicate with each other

- Information sharing:

- e.g., sharing between Android apps

- Computation speedup:

- e.g., Message Passing Interface (MPI)

- Modularity and isolation:

- e.g., Chrome’s multi-process architecture

- Information sharing:

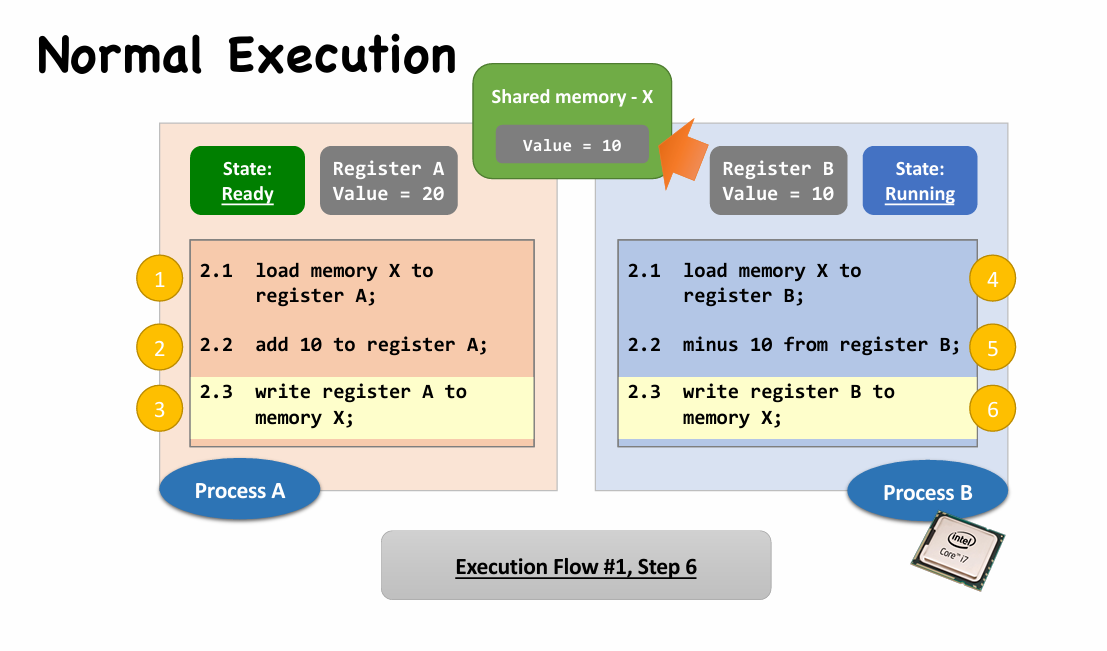

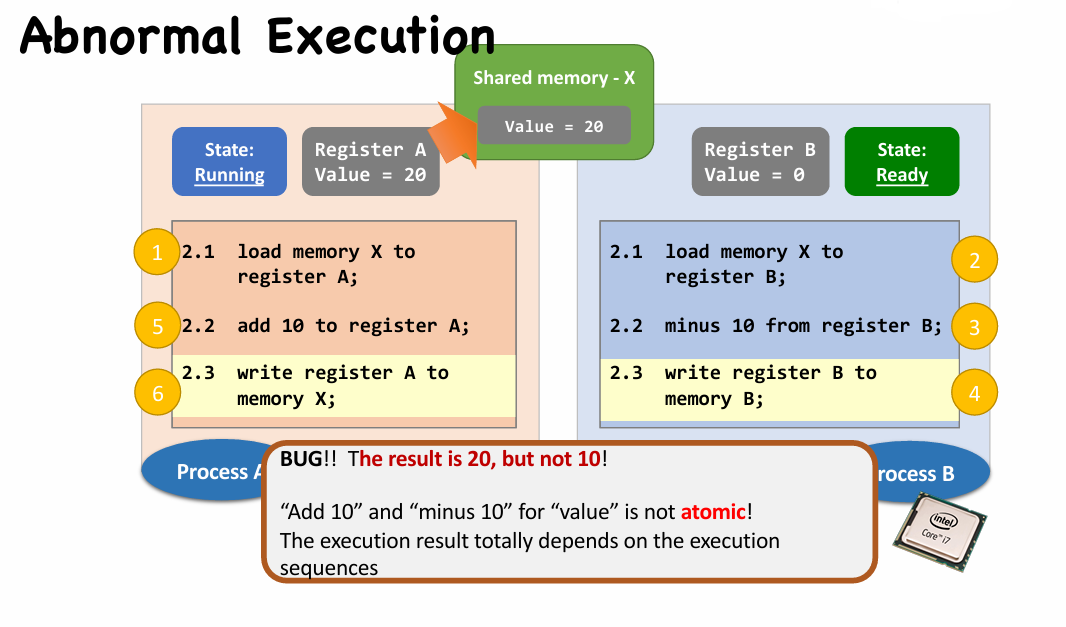

Problems: Synchronization of Threads/Processes

A Joke: A programmer had a problem. He thought to himself, “I know, I’ll solve it with threads!”. has Now problems. two he

Race Condition

|

|

- The above scenario is called the race condition.

- May happen whenever “shared object” + “multiple processes/threads” + “concurrently”

- A race condition means

- The outcome of an execution depends on a particular order in which the shared resource is accessed.

- Remember: race condition is always a bad thing and debugging race condition is a nightmare!

Solution: Critical Section

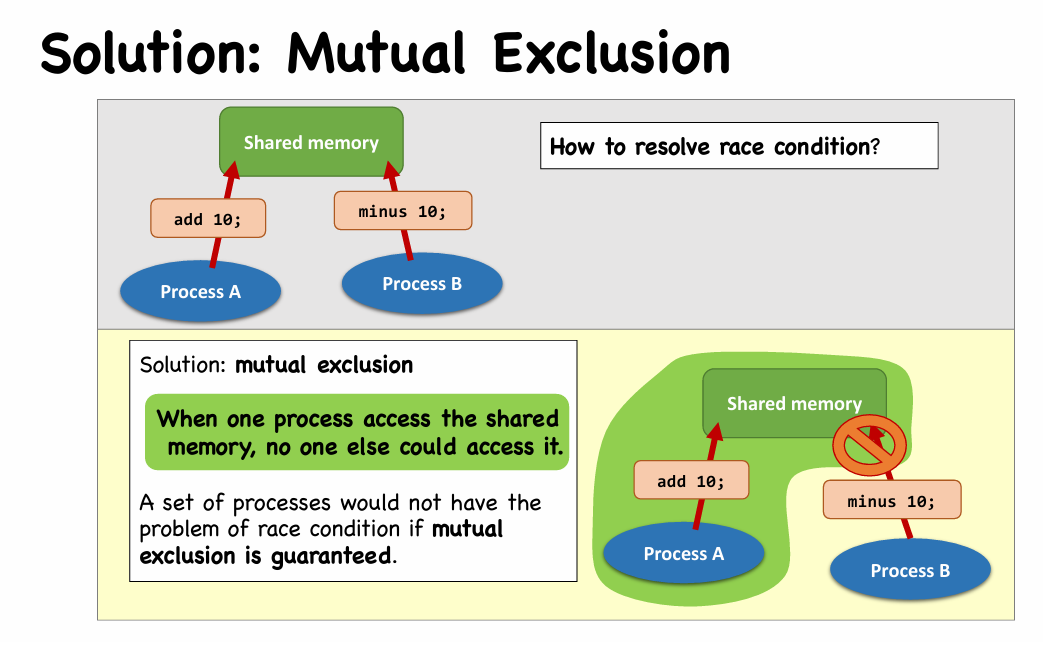

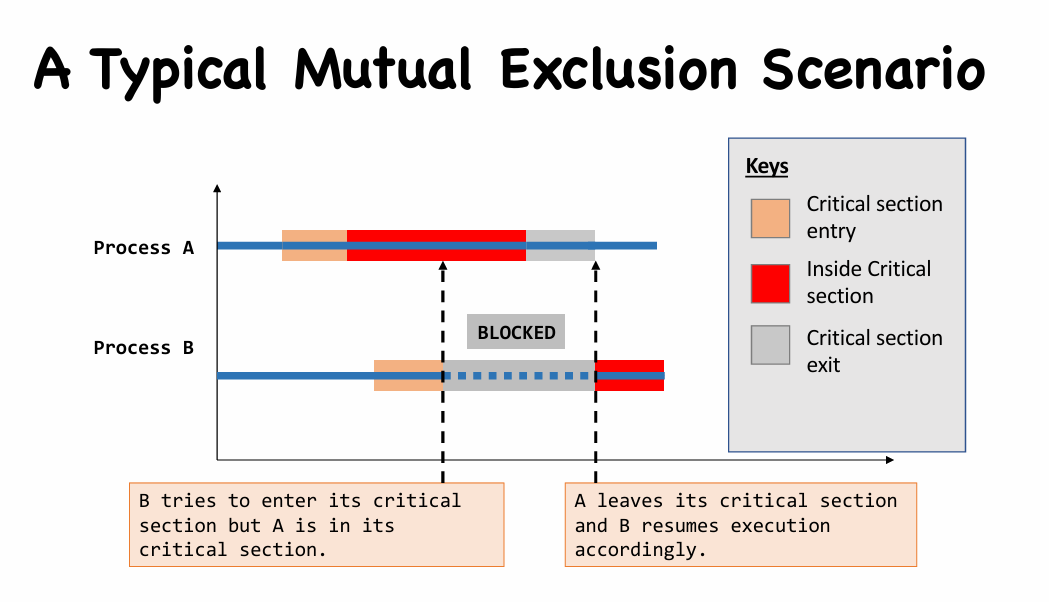

Def. Mutual Exclusion is when one process access the shared memory, no one else could access it.

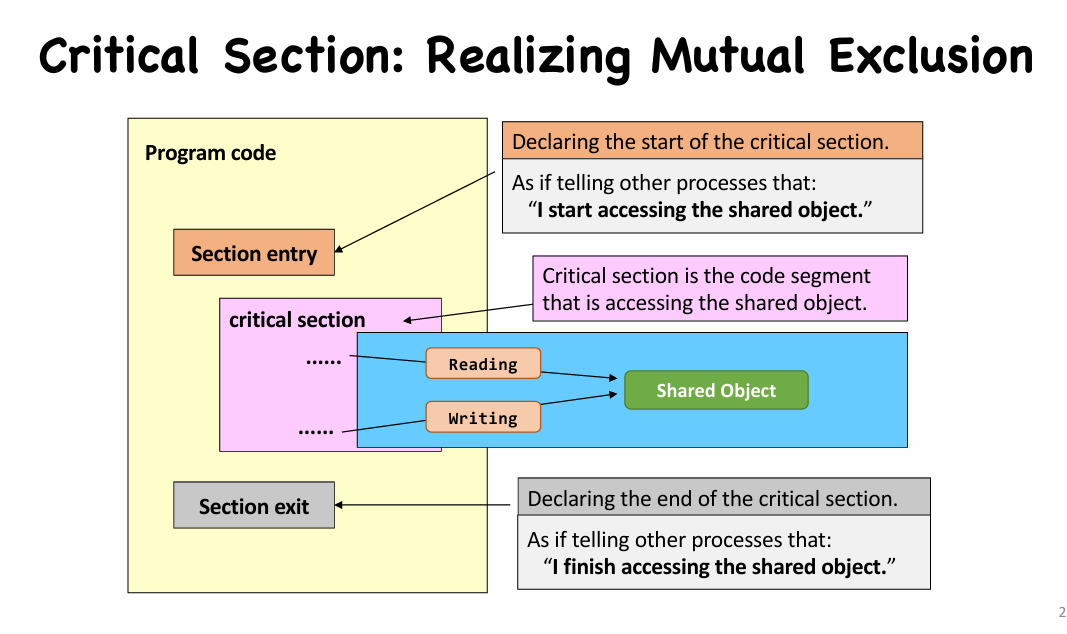

Implementation: Critical Section

|

|

- A critical section is the code segment that access shared objects.

- Critical section should be as tight as possible.

- Well, you can set the entire code of a program to be a big critical section.

- But, the program will have a very high chance to block other processes or to be blocked by other processes.

- Note that one critical section can be designed for accessing more than one shared objects.

- Critical section should be as tight as possible.

- Critical Section Implementation

- Requirement #1. Mutual Exclusion

- No two processes could be simultaneously go inside their own critical sections.

- Requirement #2. Bounded Waiting

- Once a process starts trying to enter its critical section, there is a bound on the number of times other processes can enter theirs.

- Requirement #3. Progress

- Say no process currently in critical section.

- One of the processes trying to enter will eventually get in

- Requirement #1. Mutual Exclusion

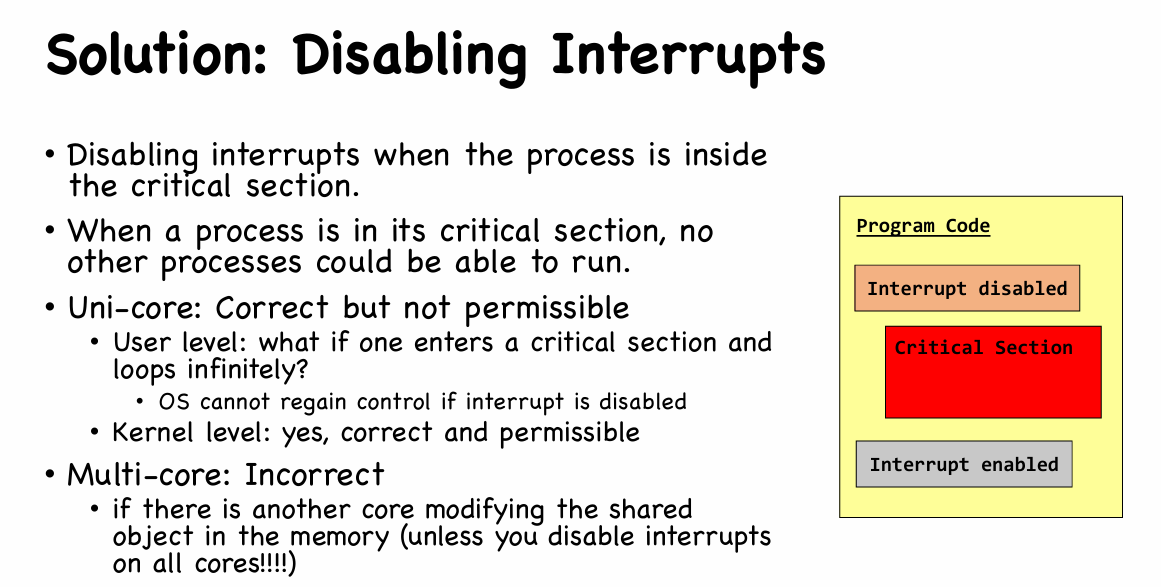

Solution: Disabling Interrupts

Solution: Spin-based Locks

Overview about Locks

- Use yet another shared objects: locks

- What about race condition on lock?

- Atomic instructions: instructions that cannot be “interrupted”, not even by instructions running on another core

- Spin-based locks

- Process synchronization

- Basic spinning using 1 shared variable

- Peterson’s solution: Spin using 2 shared variables

- Thread synchronization: pthread_spin_lock

- Process synchronization

- Sleep-based locks

- Process synchronization: POSIX semaphore

- Thread synchronization: pthread_mutex_lock

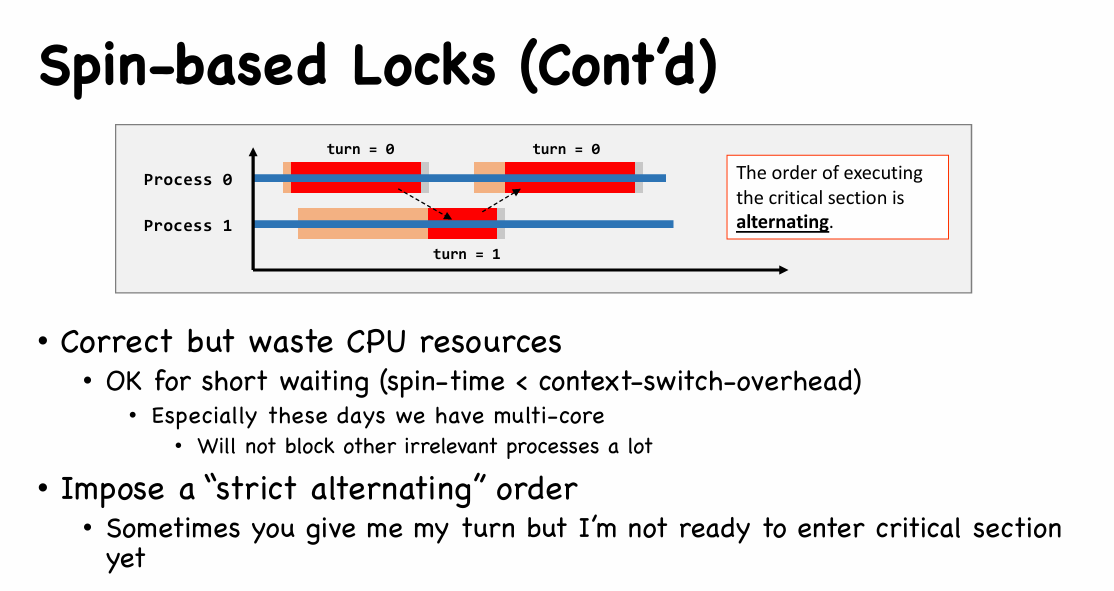

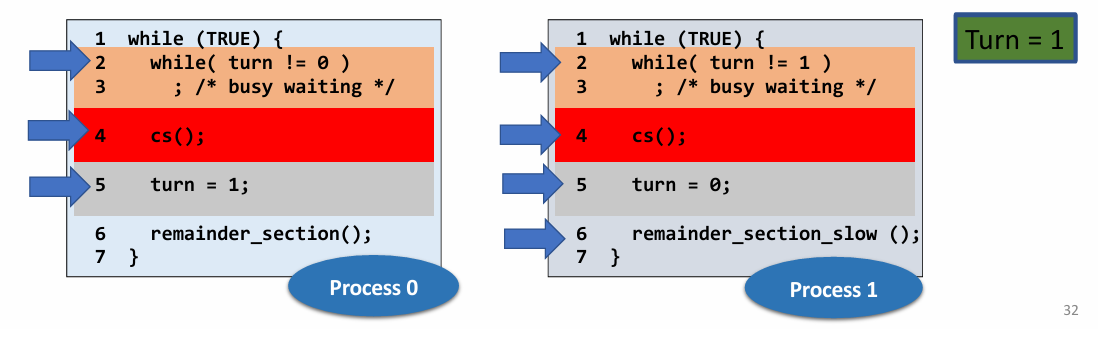

Spin-based lock

- Consider the following sequence:

- Process0 leaves

cs(), setturn=1 - Process1 enters

cs(), leavescs(), setturn=0, work on remainder_section_slow - Process0 loops back and enters

cs()again, leavescs(), setturn=1 - Process0 finishes its

remainder_section(), go back to top of the loop- It can’t enter its

cs()(as turn = 1) - That is, process0 gets blocked, but Process1 is outside its

cs(), it is at itsremainder_section_slow()

- It can’t enter its

- Process0 leaves

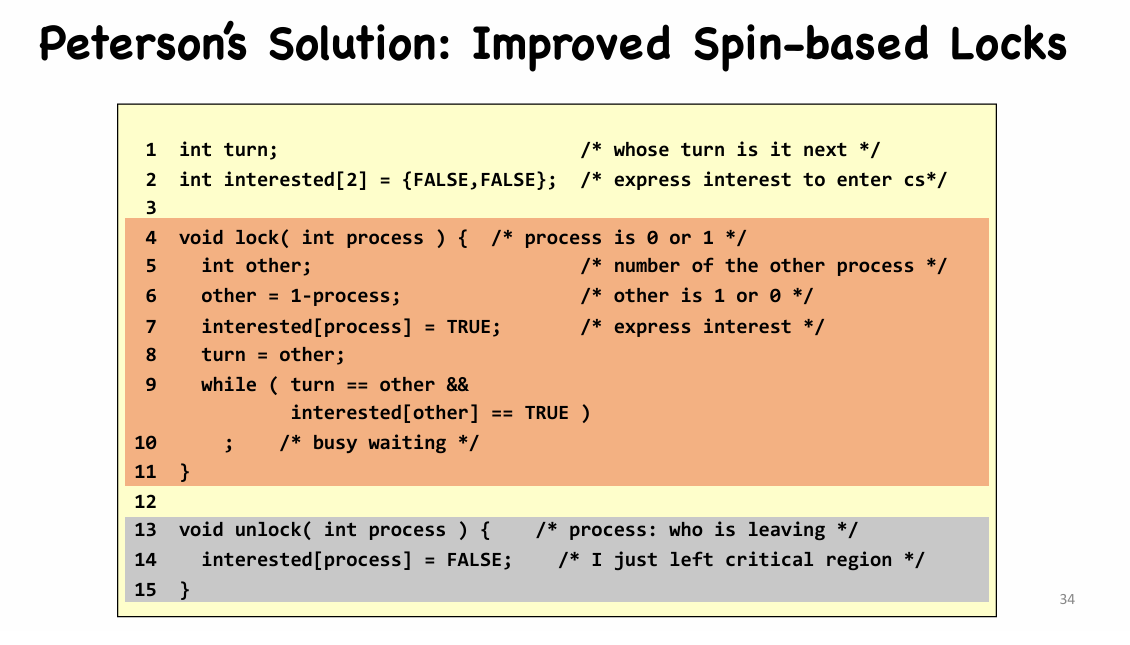

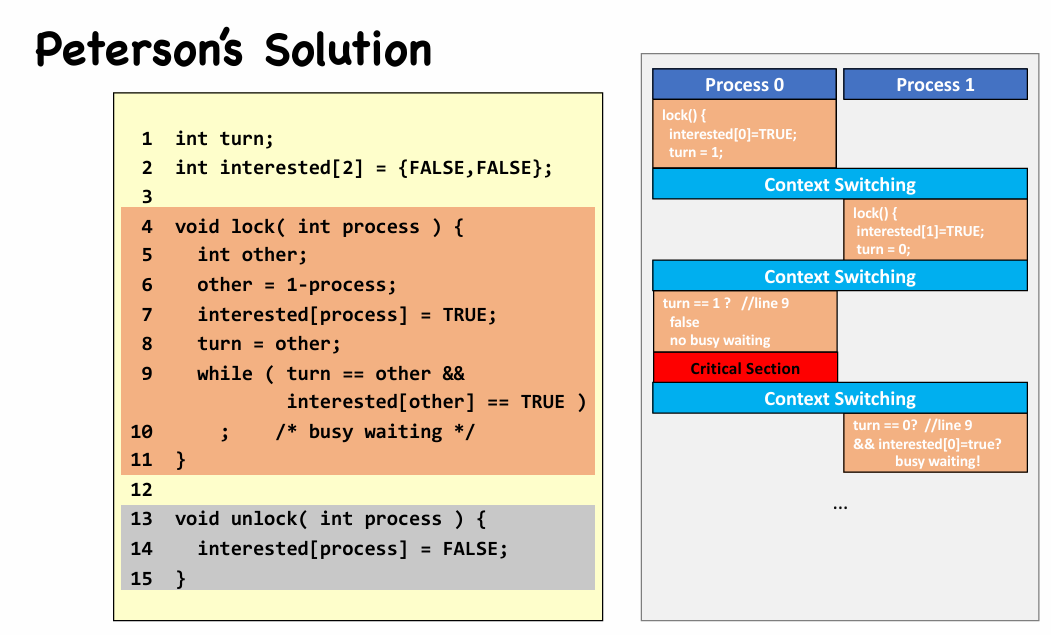

Improvement: Peterson’s Solution

引入了一个“兴趣”机制

|

|

- Mutual exclusion

interested[0] == interested[1] == trueturn == 0orturn == 1, not both

- Progress

- If only $P_0$ to enter critical section

interested[1] == false, thus $P_0$ enters critical section

- If both $P_0$ and $P_1$ to enter critical section

interested[0] == interested[1] == trueand (turn == 0orturn == 1)- One of $P_0$ and $P_1$ will be selected

- If only $P_0$ to enter critical section

- Bounded-waiting

- If both $P_0$ and $P_1$ to enter critical section, and $P_0$ selected first

- When $P_0$ exit,

interested[0] = false- If $P_1$ runs fast:

interested[0] == false, $P_1$ enters critical section - If $P_0$ runs fast:

interested[0] = true, butturn = 0, $P_1$ enters critical section.

- If $P_1$ runs fast:

Multi-Process Mutual Exclusion

- 初始化一个 waiting array 表示 n 个进程,

lock == TRUE- 当一个进程(e.g. process

i)离开 critical section 时,它会从i+1开始遍历整个 waiting array- 第一个被扫描到

waiting[j] == TRUE的进程将会进入critical section- 实现 Bounded-waiting:所有进程最多经过 $n-1$ 次即可进入 critical section

- 当不再有进程进入 critical section 时,

lock == FALSE

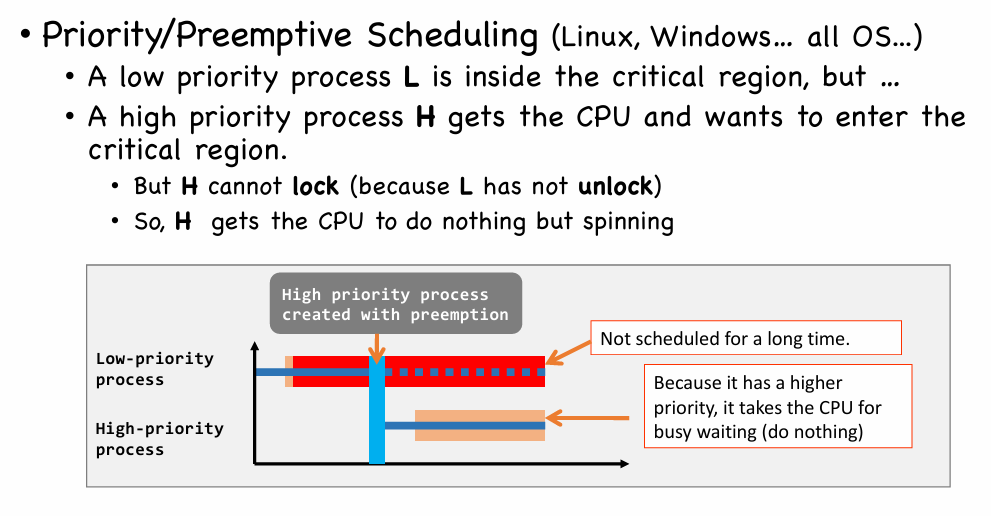

Priority Inversion

Solution: Sleep-based Locks

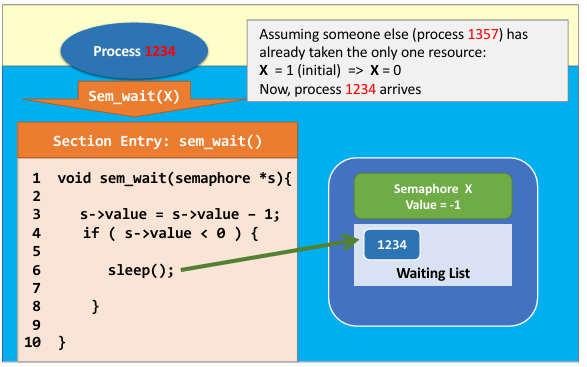

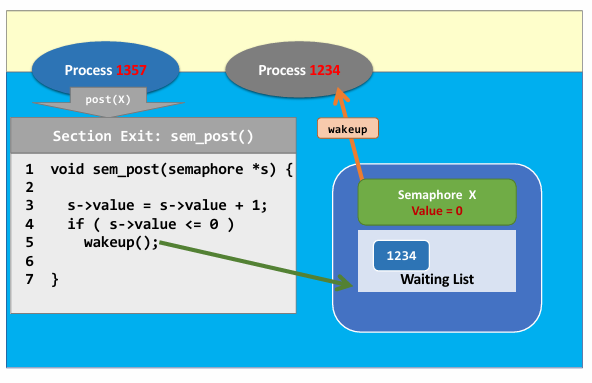

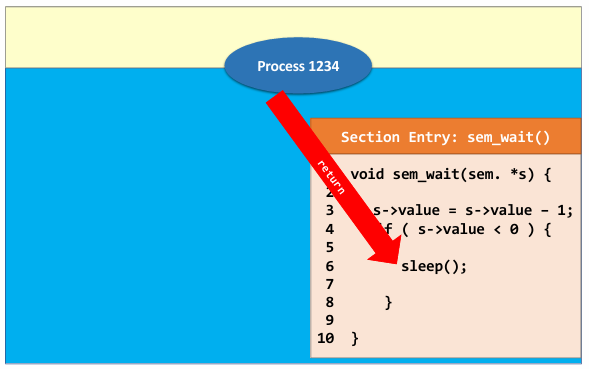

- Semaphore is just a struct, which includes

- an integer that counts the # of resources available

- Can do more than solving mutual exclusion

- a wait-list

- an integer that counts the # of resources available

- The trick is still the section entry/exit function implementation

- Must involve kernel (for sleep)

- Implement uninterruptable section entry/exit

- Disable interrupts (on single core)

- Atomic instructions (on multiple cores)

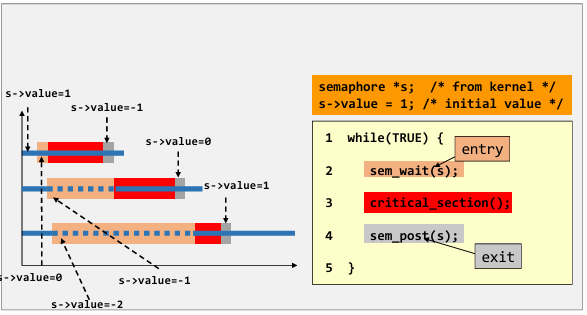

1 | // definition of sema' |

1 | // example of sema' |

- See an example 👇

|

|

|

|

- Origin value of semaphore represent the capacity of preemptive processes (

init=1, allowing at most $1$ process to take the resource) - Now process 1357 is running and take the resource (locked)

- when process 1234 arrives, value of semaphore became $-1$, so process 1234 sleep and wait.

- Process 1357 exit critical section and return the resource, calling wakeup to set value of semaphore to $0$, so that process 1234 can take the resource.

Problems solved by semaphore

- Producer-Consumer Problem

- Two types of processes: producer

- At least one producer and one consumer.

- Two types of processes: producer

- Dining Philosopher Problem

- Only one type of process

- At least two processes.

- Only one type of process

- Reader Writer Problem

- Multiple readers, one write

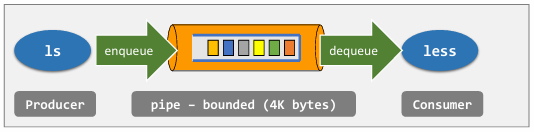

Producer-Consumer Problem

- Requirement #1: Producer wants to put a new item in the buffer, but the buffer is already full

- The producer should wait

- The consumer should notify the producer after it has dequeued an item

- Requirement #2: Consumer wants to consume an item from the buffer, but the buffer is empty

- Then consumer should wait

- The producer should notify the consumer after it has enqueued an item

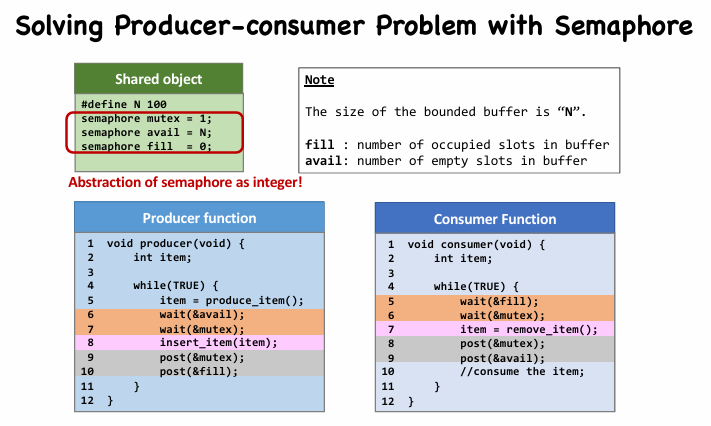

How to implement (solve) ?

- The problem can be divided into two sub-problems.

- Mutual exclusion with one binary semaphore

- The buffer is a shared object.

- Synchronization with two counting semaphores

- Notify the producer to stop producing when the buffer is full

- In other words, notify the producer to produce when the buffer is NOT full

- Notify the consumer to stop eating when the buffer is empty

- In other words, notify the consumer to consume when the buffer is NOT empty

- Notify the producer to stop producing when the buffer is full

- Mutual exclusion with one binary semaphore

- Q1: Can we only use

availand removefill?- producer

avail--by wait - consumer

avail++by post

- producer

- A1: No. If consumer get CPU first, it removes item from NULL [Error!].

- Q2: Can we switch line 6 and 7 in producer ? (wait for

mutexfirst) - A2: Consider such a case:

- The buffer is full.

- Producer wait at line 7 (wait for consumer to remove items)

- Context switch.

- Consumer pass line 5 but wait at line 6 (wait for producer to post &mutex)

- Now both producer and consumer wait for each other

- This scenario is called a deadlock

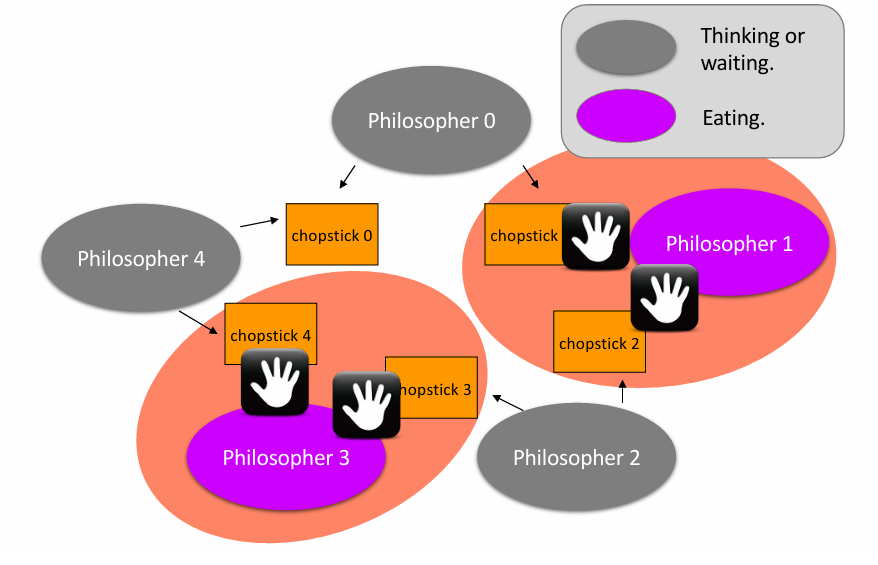

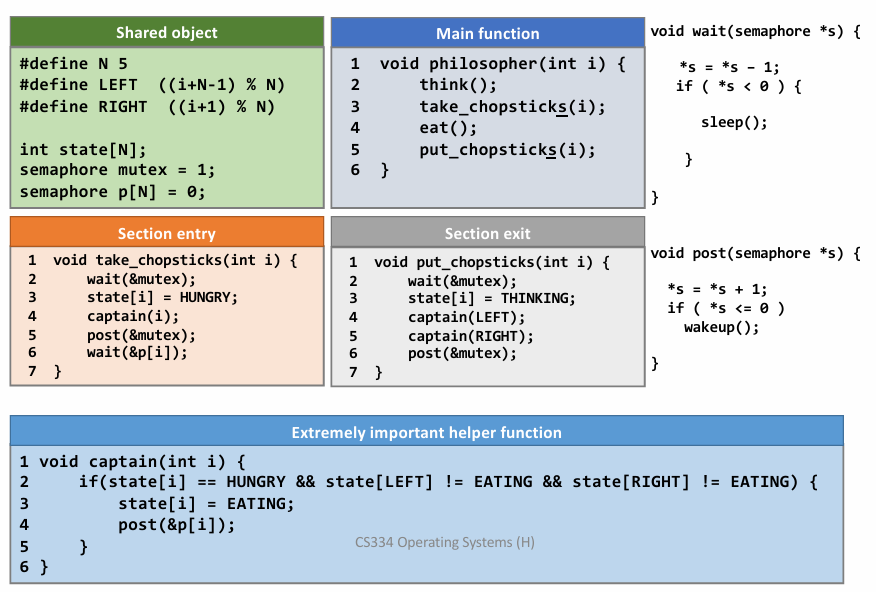

Dining Philosopher Problem

两个要求:

- 不能偷筷子,且两人不能同时用一根筷子(mutual exclusion)

- 必须避免死锁(每个人都拿了一根筷子,都吃不了东西)

初步实现:

- 一个人拿起一根筷子,如果另一根无法拿起(被占),则放下全部筷子并休息(sleep),被唤醒后再尝试

问题:可能导致全部人都重复这个操作,最后还是谁都吃不了东西

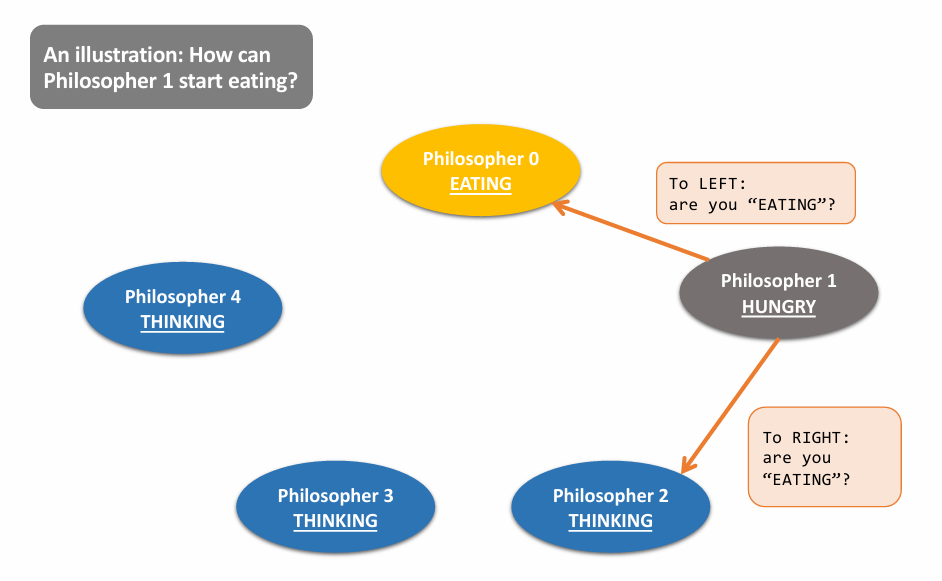

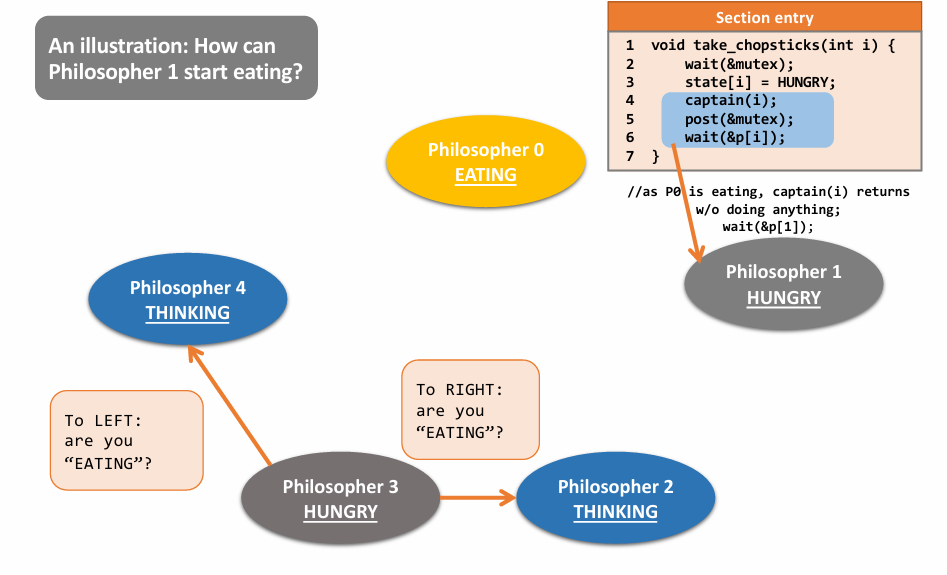

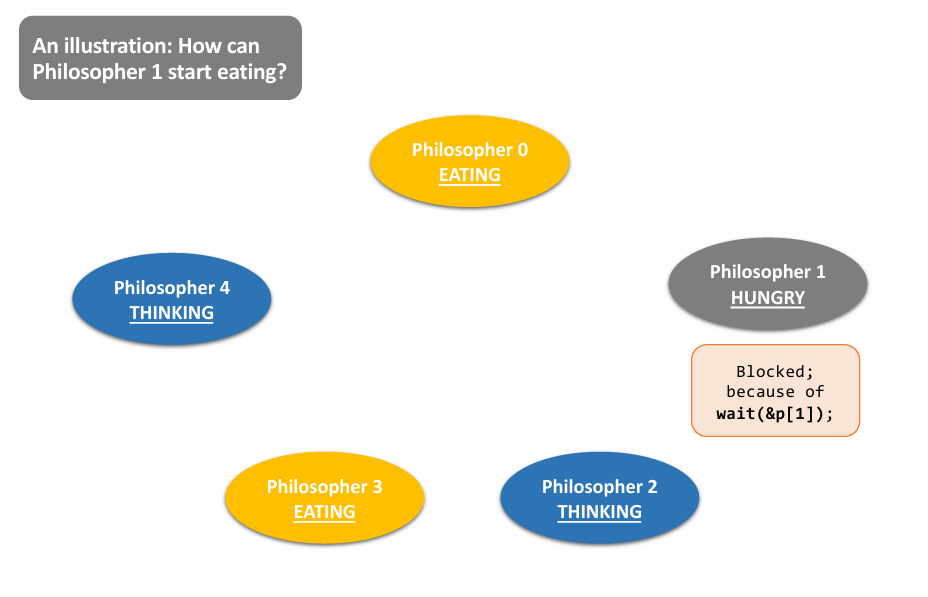

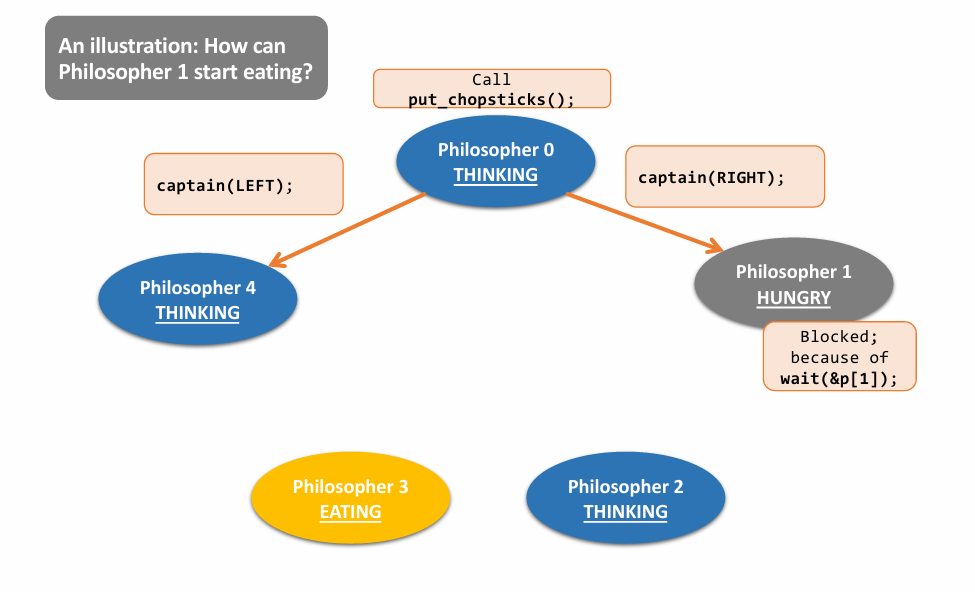

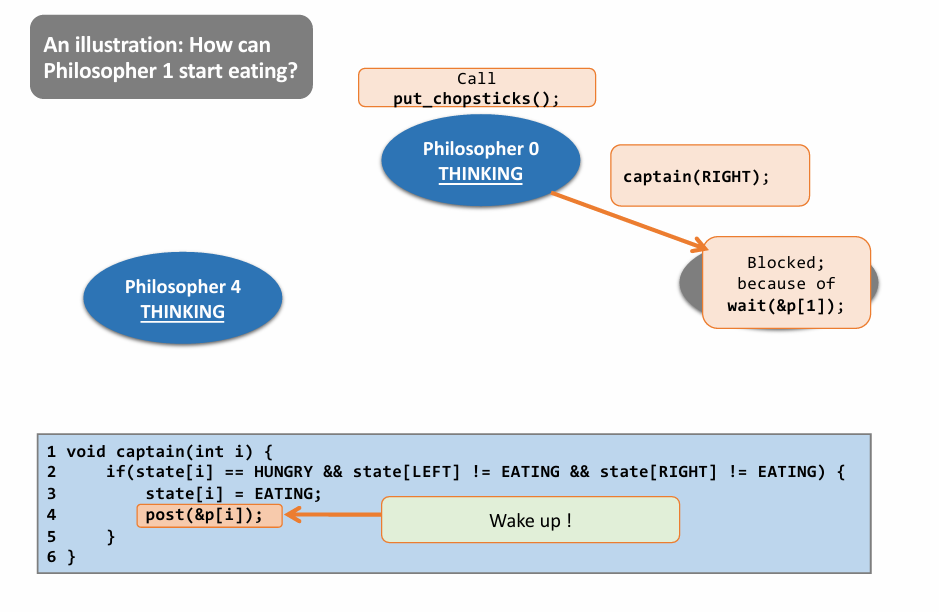

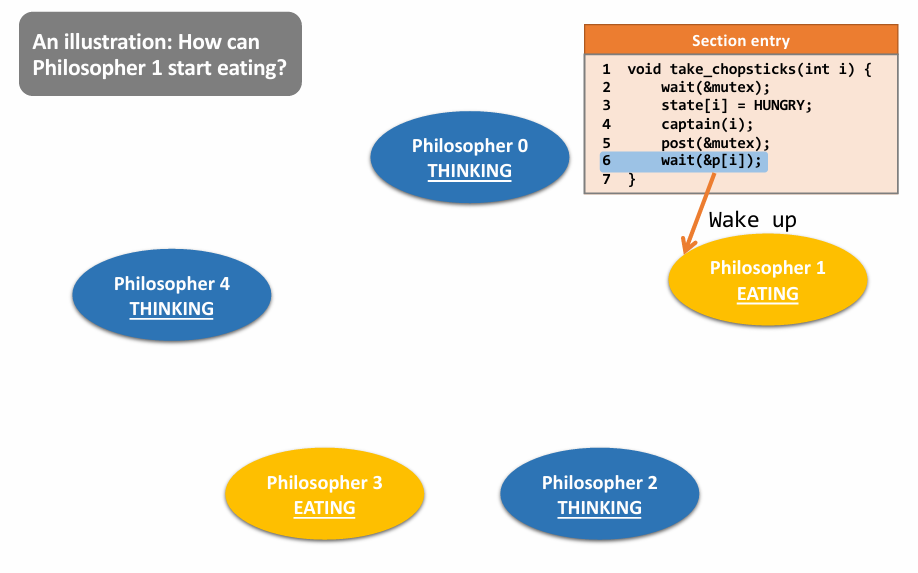

Final Solution: 👇

a case:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lec06. Address Translation

Outline

- Memory Virtualization

- Base & Bounds

- Segmentation

- Memory Allocation

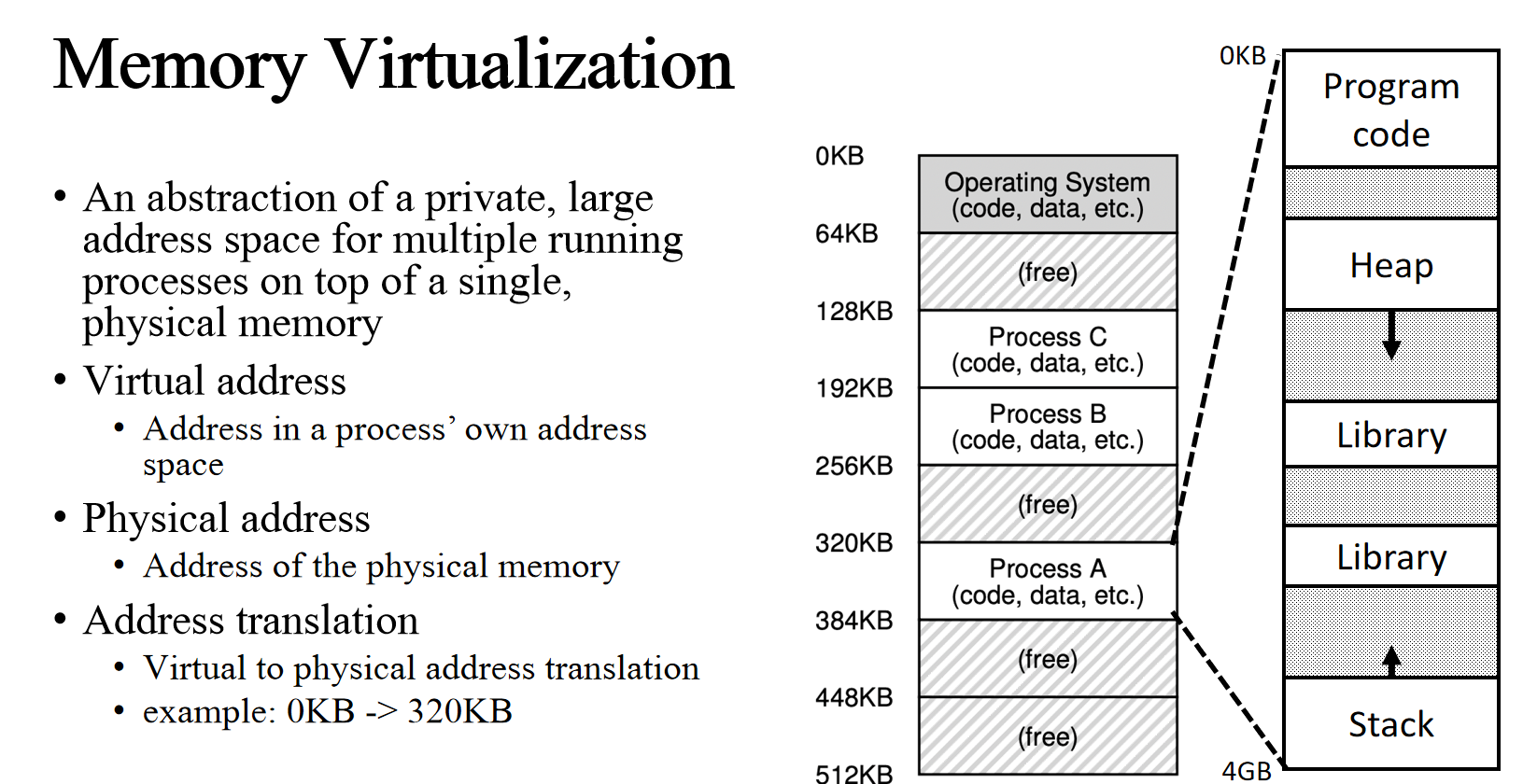

Memory Virtualization

Multiprogramming with Memory Partition brings problems to physical memory

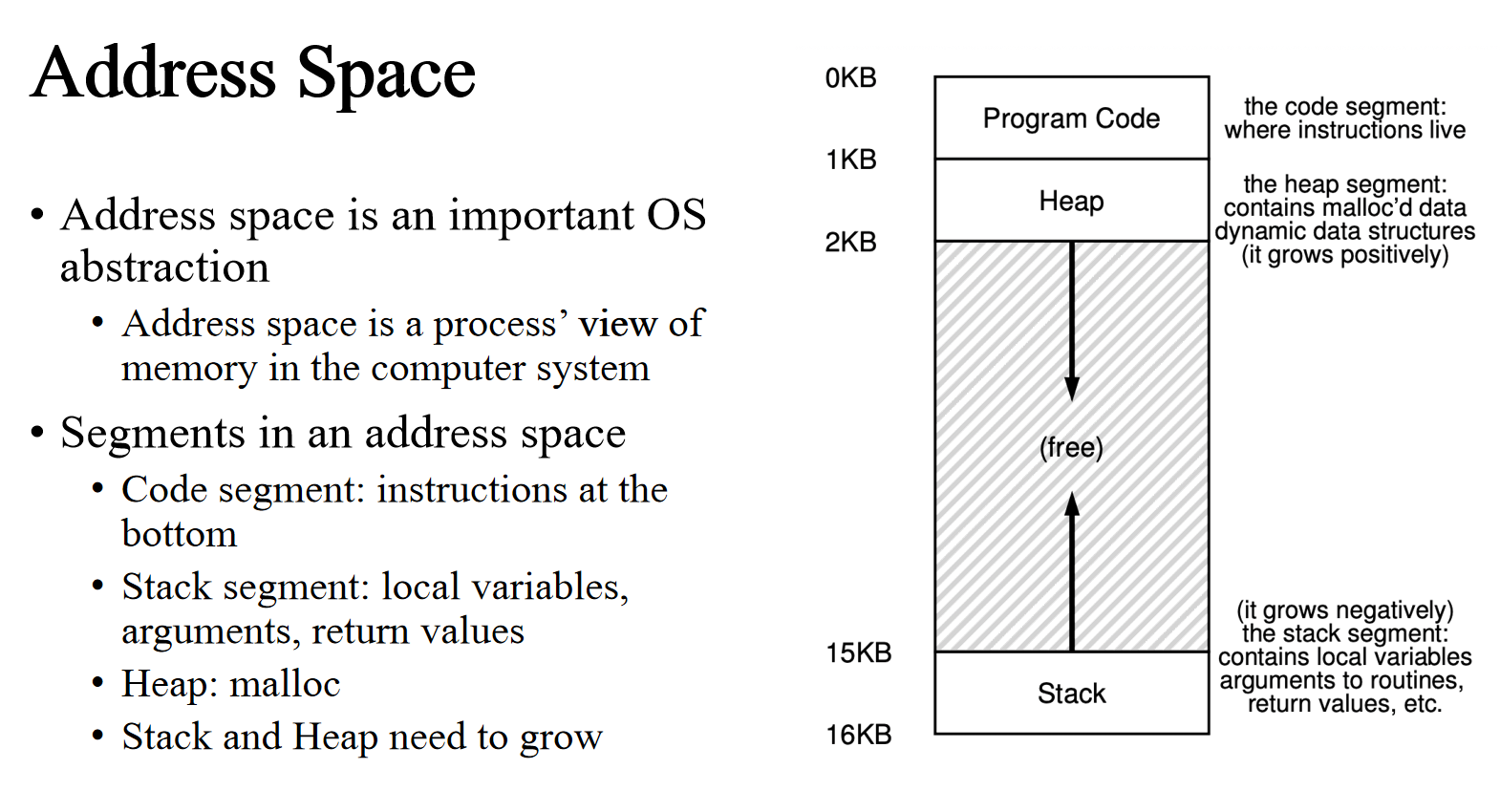

Address Space

- A mechanism that virtualize memory should

- Be transparent

- Memory virtualization should be invisible to processes

- Processes run as if on a single private memory

- Be efficient

- Time: translation is fast

- Space: not too space consuming

- Provide protection

- Enable memory isolation

- One process may not access memory of another process or the OS kernel

- Isolation is a key principle in building reliable systems

- Be transparent

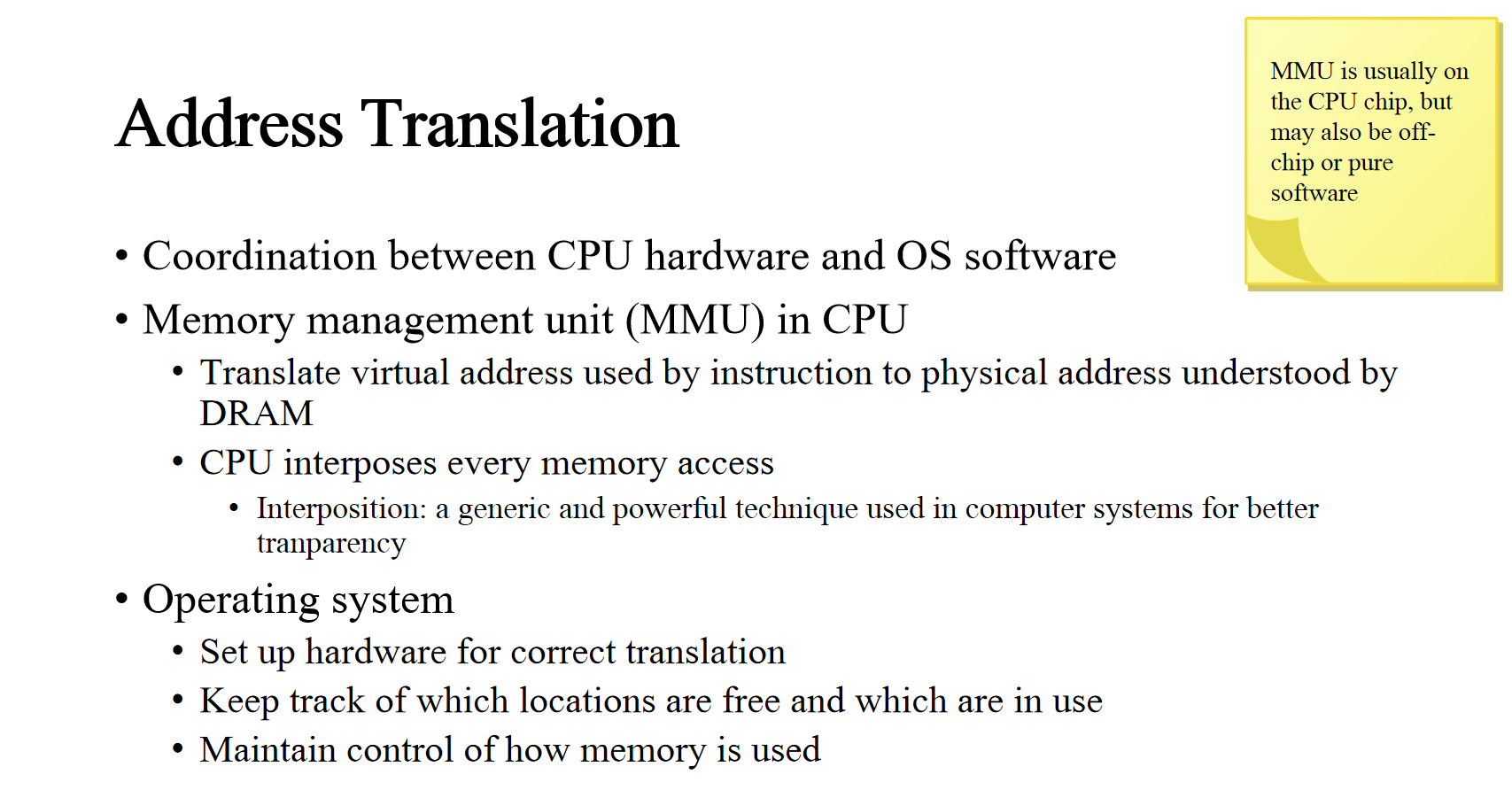

Address Translation

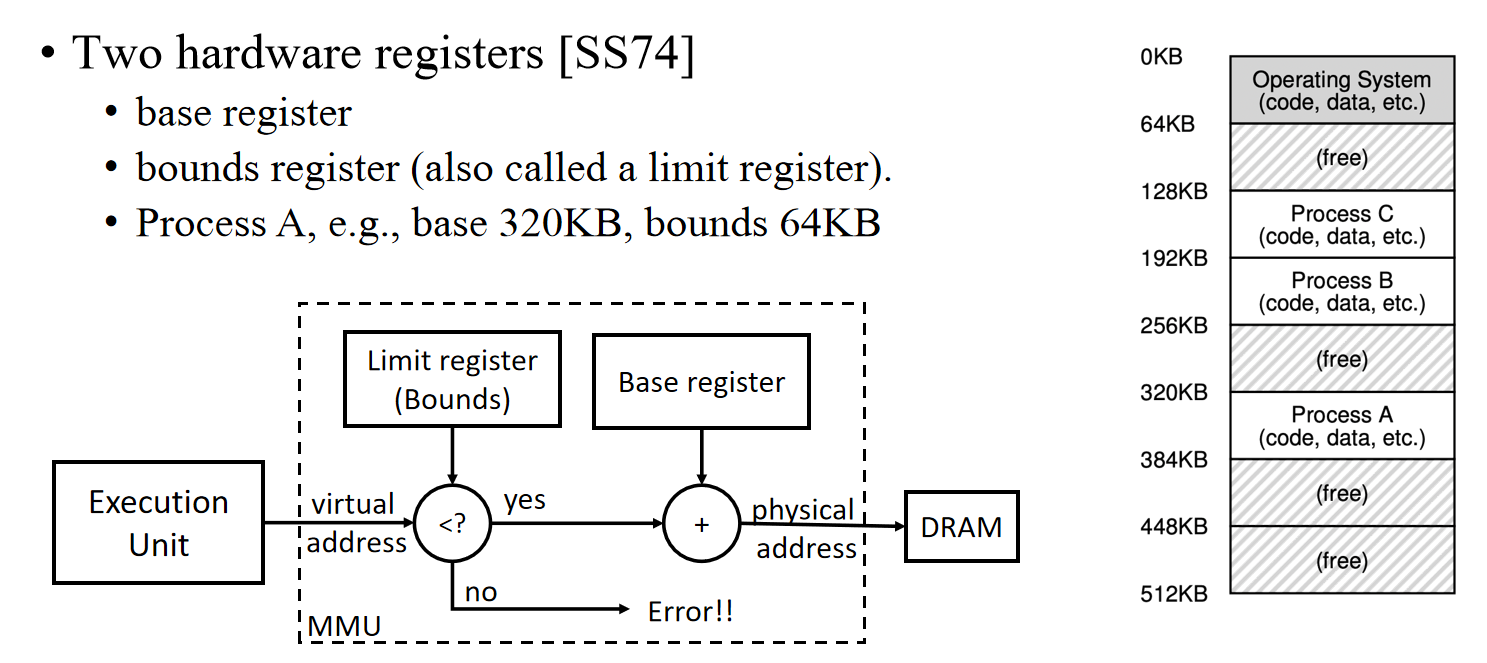

Base & Bound

| Hardware Support | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Privileged mode to update base/bounds | Needed to prevent user-mode processes from executing privileged operations to update base/bounds |

| Base/bounds registers | Need pair of registers per CPU to support address translation and bounds checks |

| Privileged instruction(s) to register exception handlers | Need to allow OS, but not the processes, to tell hardware what exception handlers code to run if exception occurs |

| OS Support | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Memory management | Need to allocate memory for new processes; Reclaim memory from terminated processes; manage memory via free list |

| Base/bounds management | Must set base/bounds properly upon context switch |

| Exception handling | Code to run when exceptions arise; likely action is to terminate offending process |

Limitation

- Internal fragmentation .

- wasted memory between heap and stack

- Cannot support larger address space .

- Address space equals the allocated slot in memory

- E.g. Process C’s address space is at most 64KB .

- Hard to do inter-process sharing .

- Want to share code segments when possible

- Want to share memory between processes

- E.g. Process A & C cannot share memory .

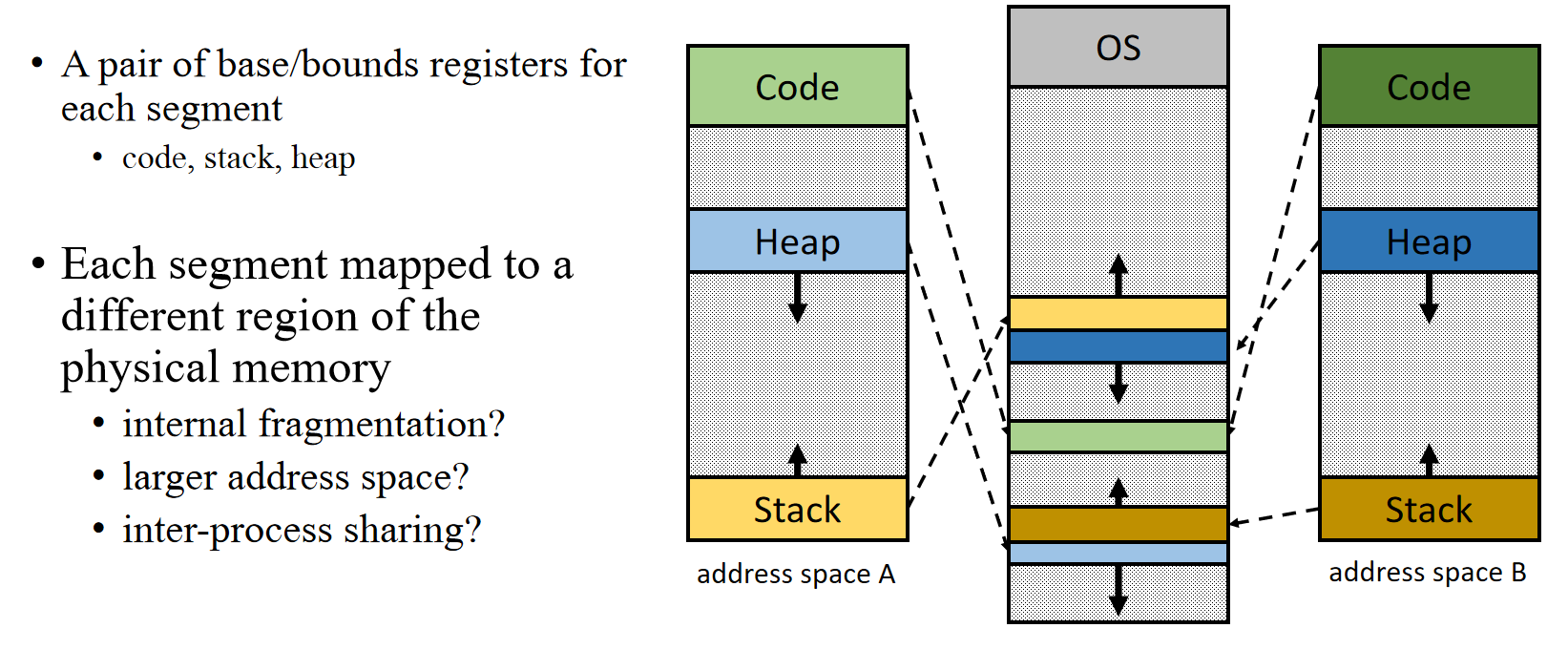

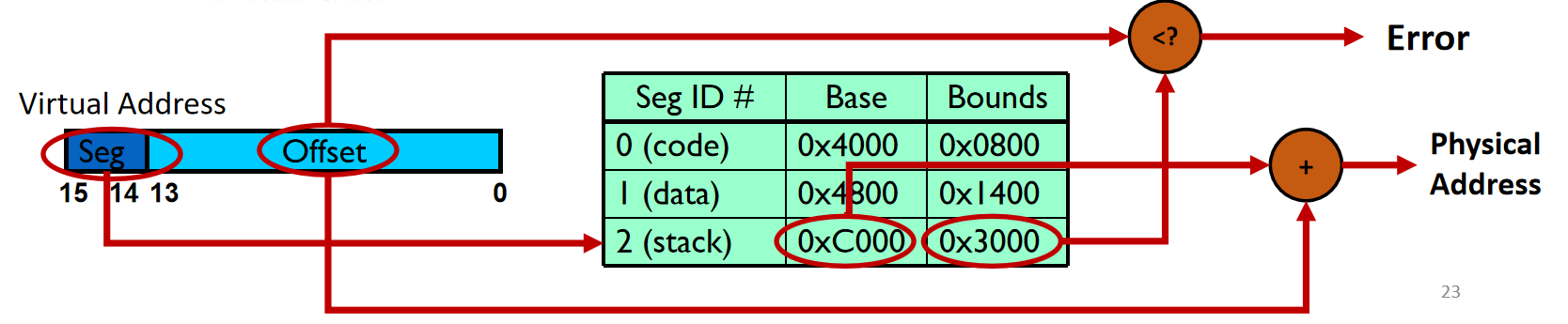

Segmentation: Generalized Base/Bounds

Implementation

- Base/bounds registers organized as a table

- Segment ID used to index the base/bounds pair

- Base added to offset (of virtual address) to generate physical address

- Error check catches offset (of virtual address) out of range

- Use segments explicitly

- Segment addressed by top bits of virtual address

- Use segments implicitly

- e.g., code segment used for code fetching

- Memory sharing with segmentation

- Code sharing on modern OS is very common

- If multiple processes use the same program code or library code

- Their address space may overlap in the physical memory

- The cooresponding segments have the same base/bounds

- Memory sharing needs memory protection

- Memory protection with segmentation

- Extend base/bounds register pair

- Read/Write/Execute permission

Problems with Segmentation

- OS context switch must also save and restore all pairs of segment registers

- A segment may grow, which may or may not be possible

- Management of free spaces of physical memory with variable sized segments

- External fragmentation: gaps between allocated segments

- Segmentation may also have internal fragmentation if more space allocated than needed. (一个 seg 内的 heap 和 stack 之间存在内部碎片,浪费了过多分配的空间)

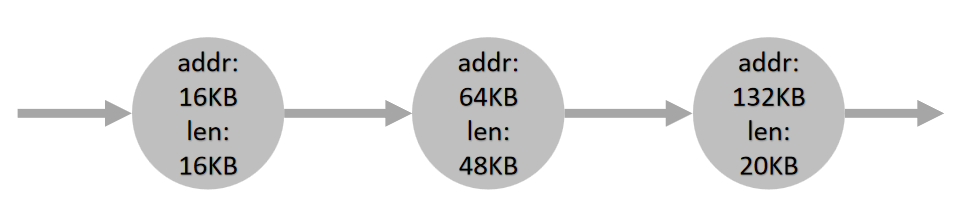

Memory Allocation

- OS needs to manage all free physical memory regions

- A basic solution is to maintain a linked list of free slots

- An ideal allocation algorithm is both fast and minimizes fragmentation. (sometimes need trade-off)

Some Strategies

| Strategy | Idea | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best fit |

|

Satisfy the request with minimal external fragmentation | exhaustive search is slow |

| Worst fit |

|

Leaves larger “holes” in physical memory |

|

| First fit | find the first block that is big enough and returns the requested size | Fast | pollutes the beginning of the free list with small chunks |

Lec07. Paging

Outline

- Introduction to paging

- Multi-level page tables

- Other page table structures

- Real-world paging schemes

- Translation lookaside buffer (TLB)

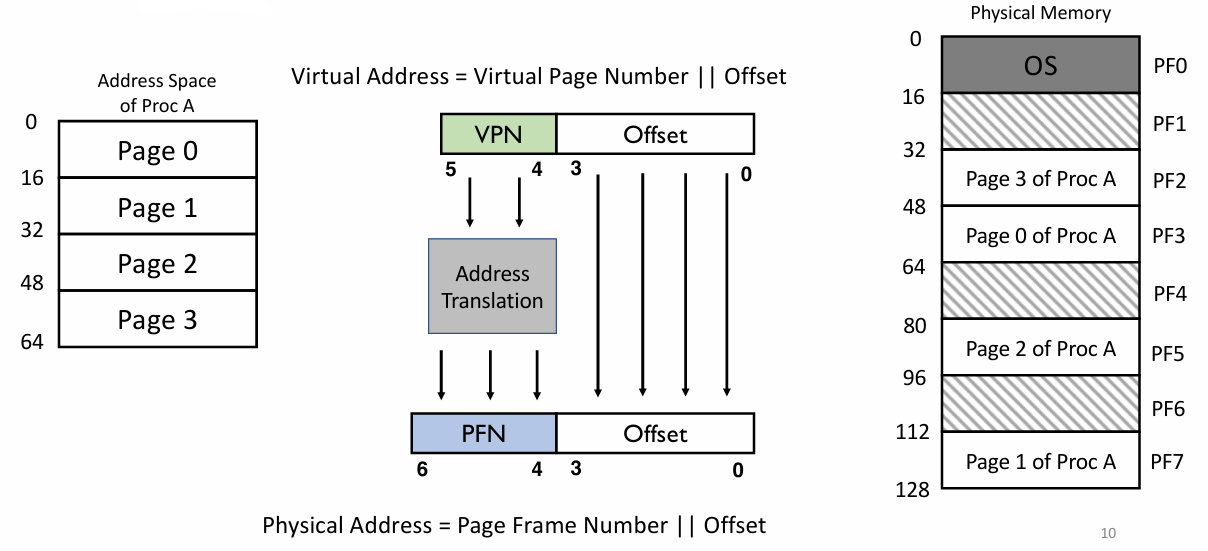

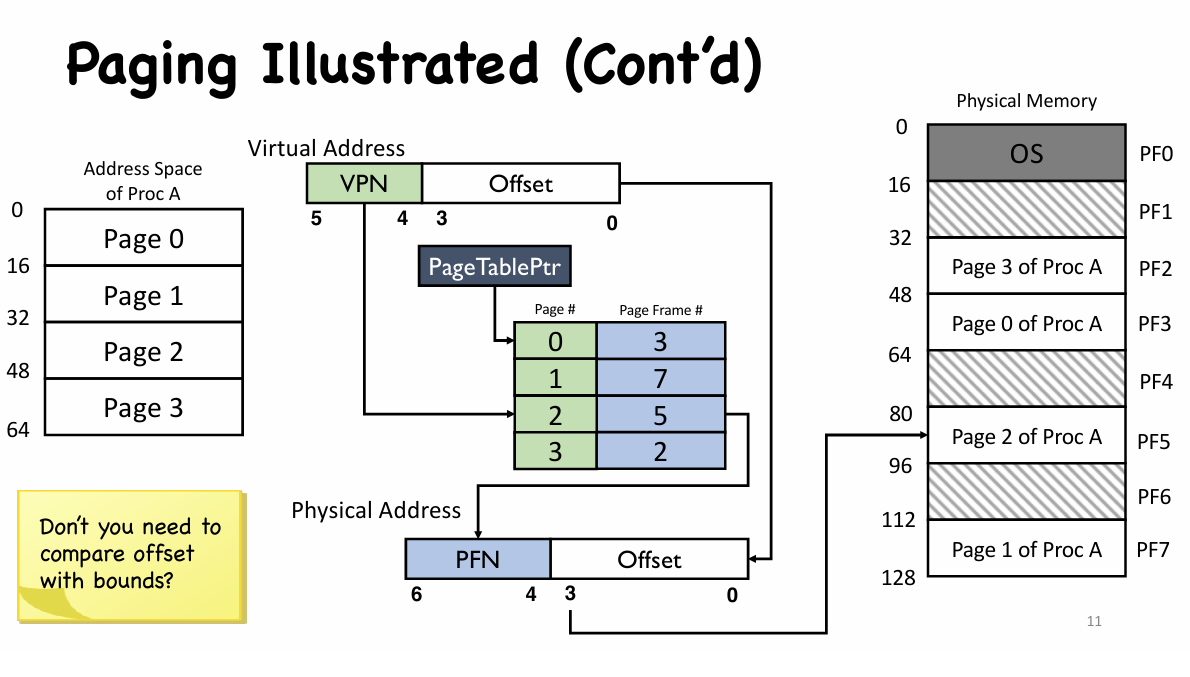

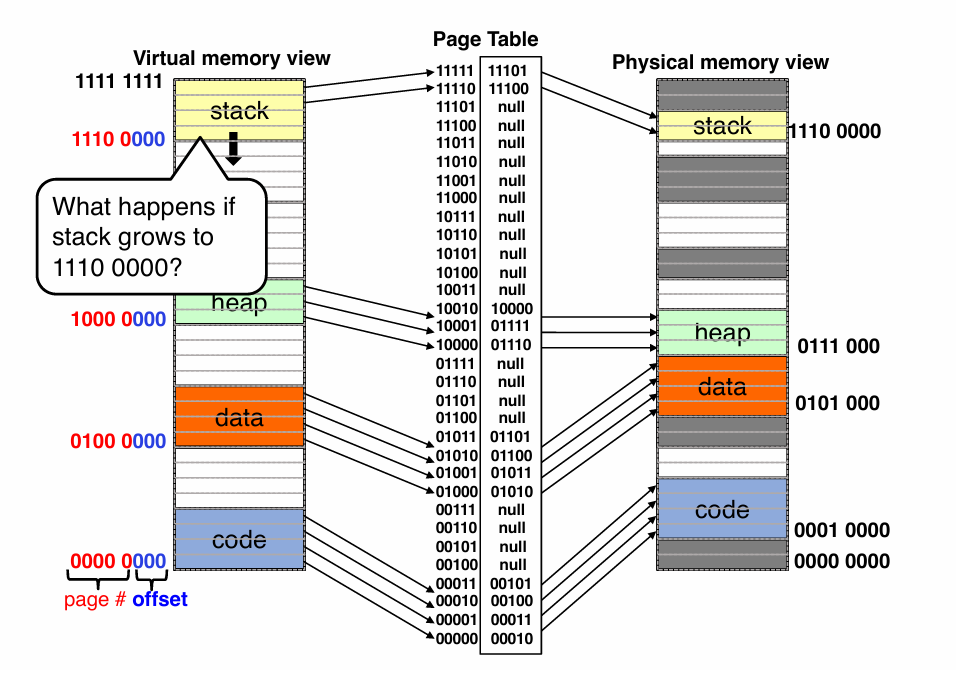

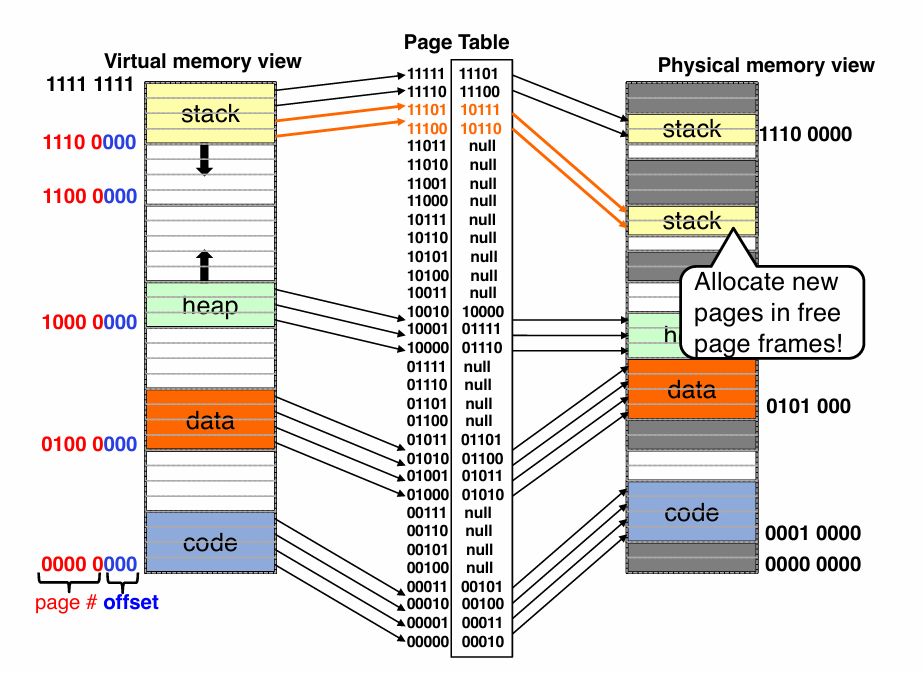

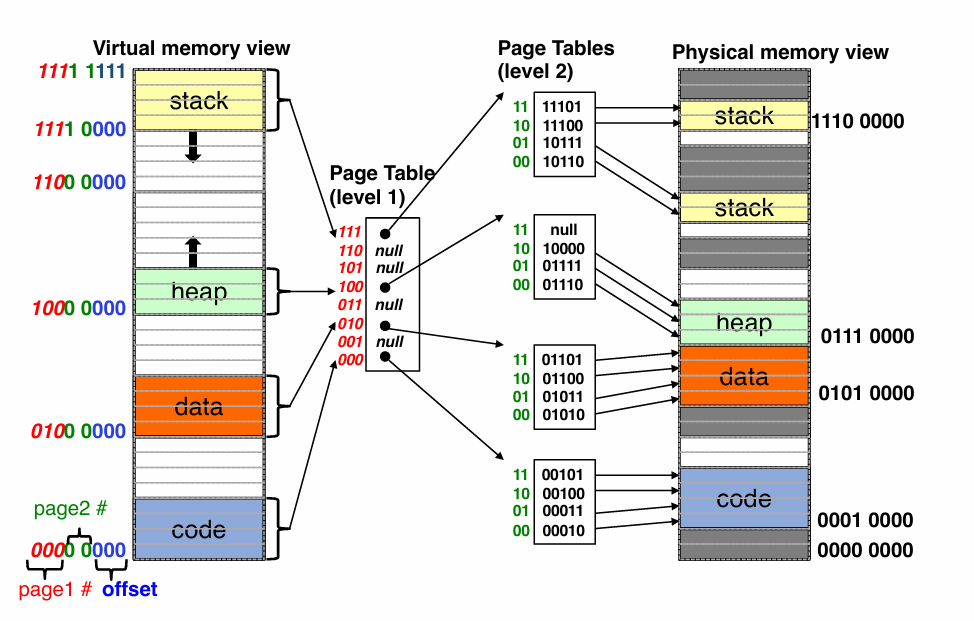

Intro to Paging

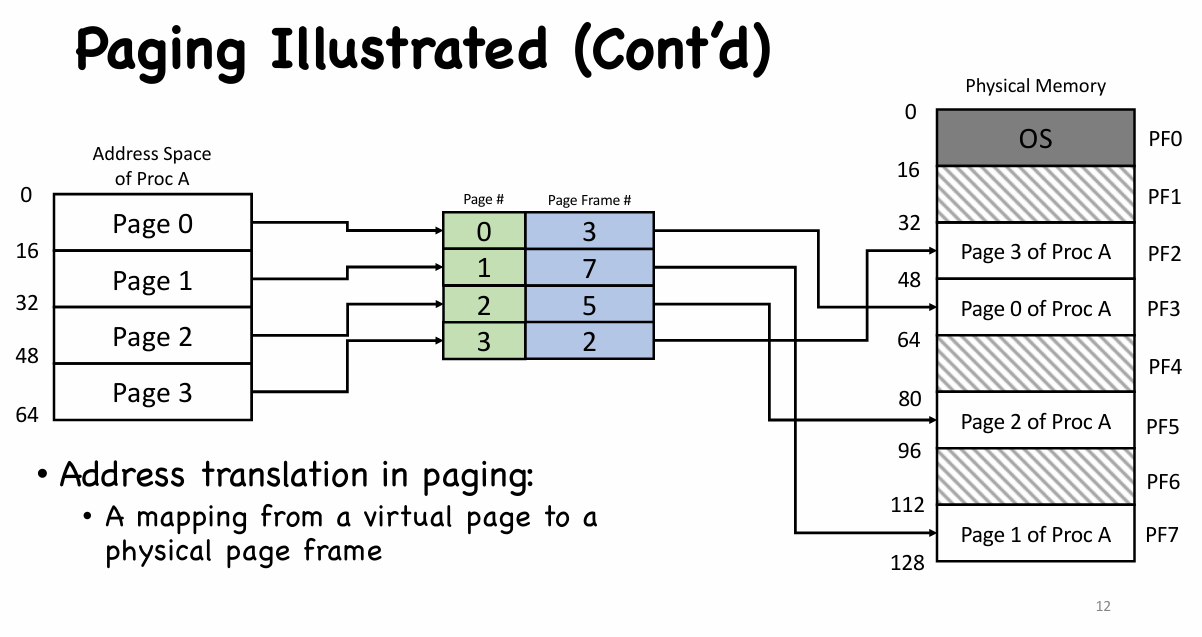

Recall: Solutions on segmentation

- Physical memory conceptually divided into fixed size

- Each is a page frame

- Too big → internal fragmentation

- Too small → page table too big

- Each is a page frame

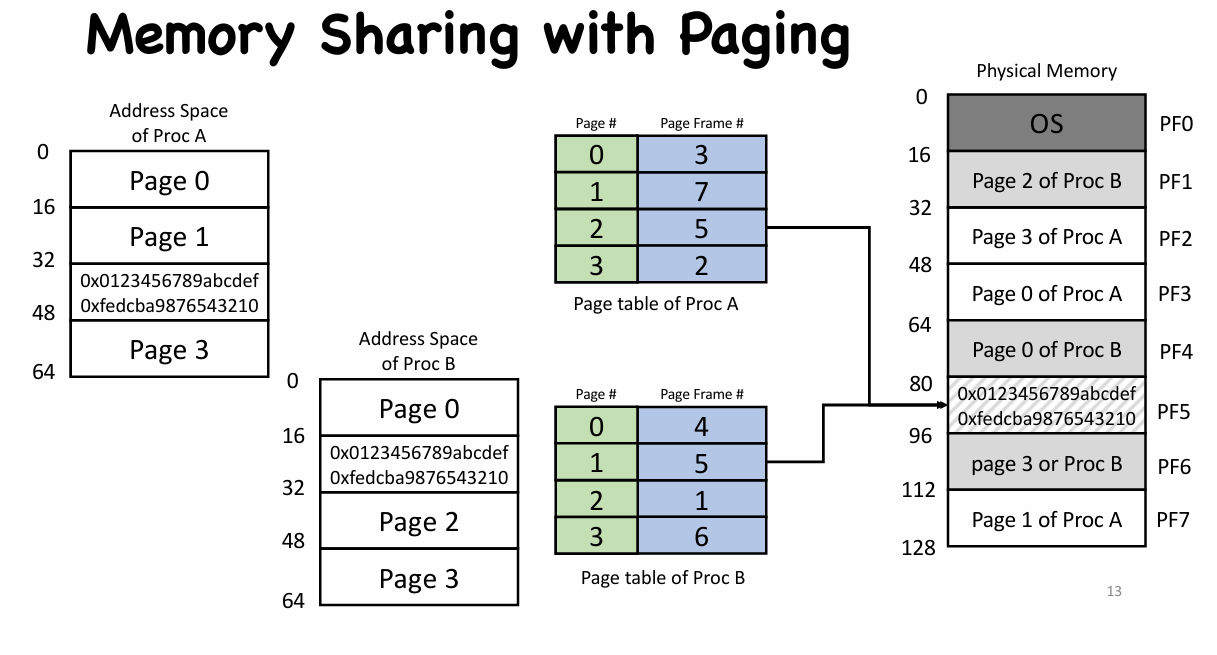

- Virtual address space conceptually divided into the same size

- Each is a page

- Page mapped to page frame

- One-to-one mapping

- Many-to-one mapping 👉 memory sharing

- One page table per process

- Resides in physical memory

- One entry for one virtual $\to$ physical translation

- Resides in physical memory

|

|

|

|

- Virtual Address and Paging

- Length of virtual address determines size of address space

- Length of offset determines size of a page / page frame

- In case of m-bit virtual address and k-bit offset

- Size of address space: $2^m$

- Size of a page: $2^k$

- e.g., 32-bit virtual address, 4KB page: $m = 32$, $k = 12$

- Page Table Entry

- An entry in the page table is called a page table entry (PTE).

- Besides PFN (Page Frame Number), PTE also contains a valid bit

- Virtual pages with no valid mapping: valid bit = 0

- Important for sparse address space (e.g., $2^{64}$ bytes)

- PTE also contains protection bits

- Permission to read from or write, or execute code on this page

- PTE also contains an access bit, a dirty bit, a present bit

- Present bit: whether this page is in physical memory or on disk

- Dirty bit: whether the page has been modified since it was brought into memory

- Access bit: whether a page has been accessed

|

|

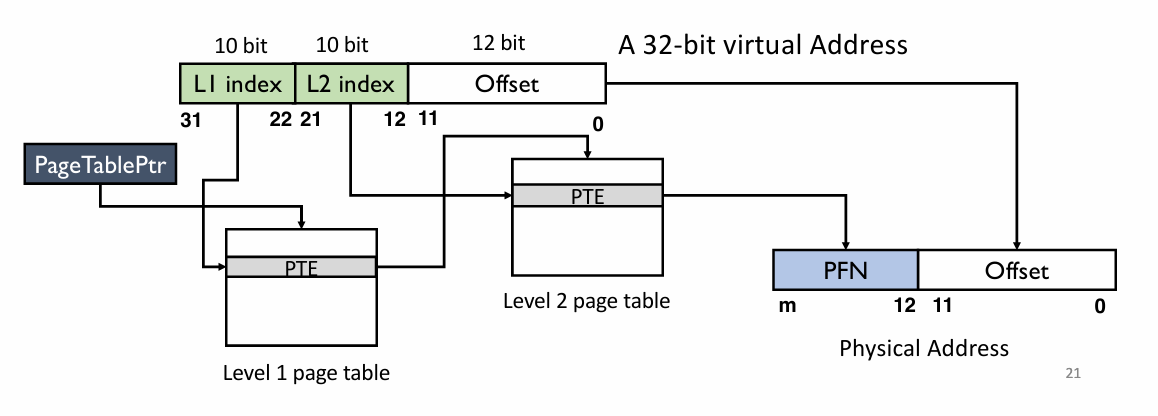

Multi-level page tables

- Two level Page Tables

- in order to save space

- using “Tree” instead of “List” to improve performance

More detail about …

Other Page Table Strctures

- Hierarchical page tables

- 2-level page tables

- 3-level page tables

- 4-level page tables

- Hashed Page Tables

- Inverted Page Tables

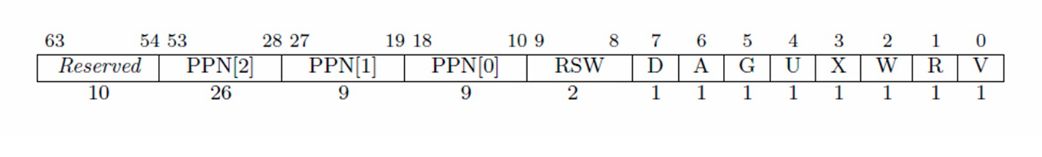

Real-world Paging Scheme

I. RISC-V support multiple MMU

RV32: SV32RV64: SV39 & SV48

II. IA-32 (Intel’s 32-bit CPU) uses two stage address translation: segmentation + paging

Issues of Paging

- Time Complexity

- Extra memory references during address translation

- Three-level page tables requires 3 additional memory reads

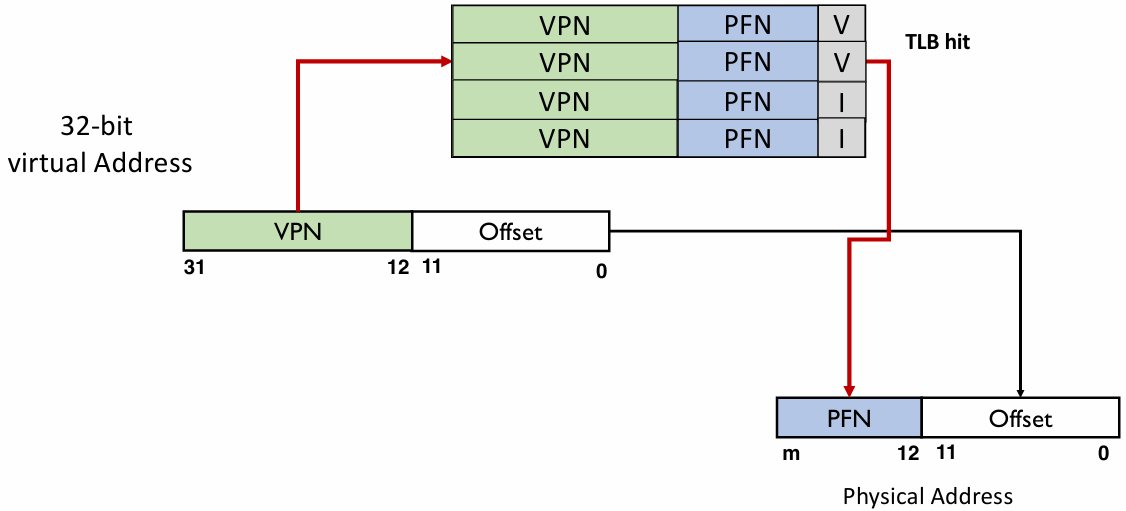

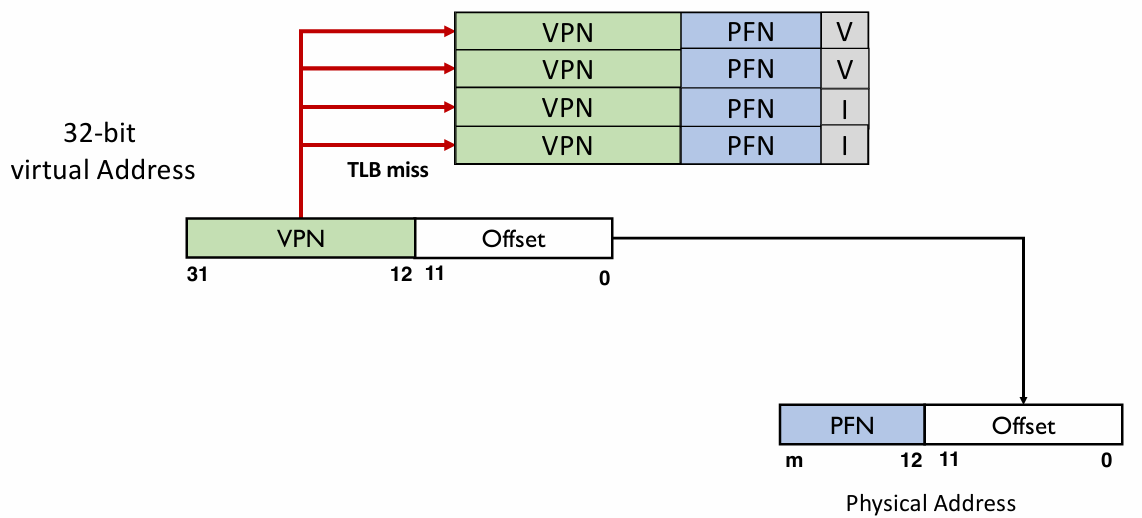

Translation Lookaside Buffer

- A translation lookaside buffer (TLB) is a hardware cache that is part of the MMU (Memory Management Unit)

- A cache for the PTEs: holding a translation likely to be re-used

- Replacement policy: LRU (Recall for “Computer Organization”), FIFO, random

- Each entry holds mapping of a virtual address to a physical address

- A cache for the PTEs: holding a translation likely to be re-used

- Before a virtual-to-physical address translation is to be performed, TLB is looked up using VPN

- TLB hit: VPN is found, and the PFN of the same entry used

- TLB miss: VPN not found, page table walk

Thought: can TLB be big?

No. If it’s too big, it cannot function as speed-up.

- Issues with Context Switch

- Two process may use the same virtual address

- e.g.

P1: 100->170,P2: 100->110

- e.g.

- Solutions:

- Flush TLB upon context switch (Invalidate all entries:

V->I) - Extending TLB with address space ID (No need to flush TLB)

- Flush TLB upon context switch (Invalidate all entries:

- Two process may use the same virtual address

Lec08. Demand Paging

Outline

- Demand Paging Mechanisms

- Page Replacement Policy

- Page Frame Allocation

Demand Paging Mechanisms

Who is responsible for moving data?

For applications, it’s memory overlay

- Application in charge of moving data between memory and disk

- e.g., calling a function needs to make sure the code is in memory!

For OS, it’s demand paging

- OS configures page table entries

- Virtual page maps to physical memory or files in disk

- Process sees an abstraction of address space

- OS determines where the data is stored

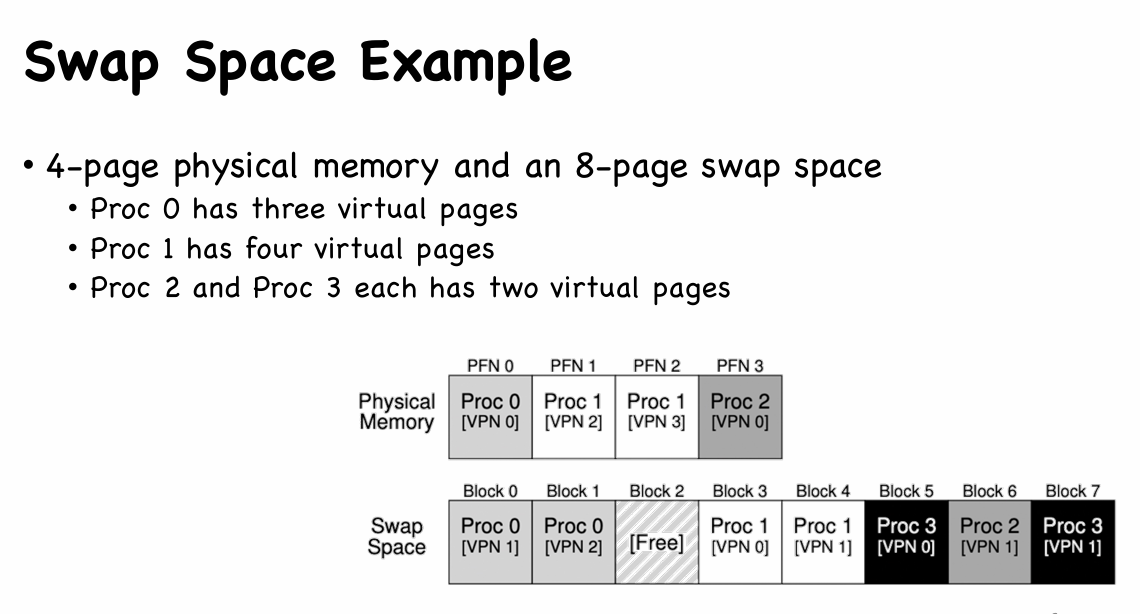

Swap Space

- Swap space is a partition or a file stored on the disk

- OS swaps pages out of memory to it

- OS swaps pages from it into memory

- Swap space conceptually divided into page-sized units

- OS maintains a disk address of each page-sized unit

Demand Paging

- Load pages from disk to memory only as they are needed

- Pages are loaded “on demand”

- Data transferred in the unit of pages

- Two possible on-disk locations

- Swap space:

- created by OS for temporary storage of pages on disk

- e.g., pages for stack and heap

- Program binary files:

- The code pages from this binary are only loaded into memory when they are executed

- Read-only, thus never write back

- Swap space:

Physical Memory as a Cache

- Physical memory can be regarded as a cache of on-disk swap space

- Block size of the cache?

- 1 page (4KB)

- Cache organization (direct-mapped, set-associative, fully-associative)?

- Fully associative: any disk page maps to any page frame

- What is page replacement policy?

- LRU, Random, FIFO

- What happens on a miss?

- Go to lower level to fill page (i.e. disk)

- What happens on a write, write-through or write back?

- write-back: changes are written back to disk when page is evicted (Recall for Computer Organization)

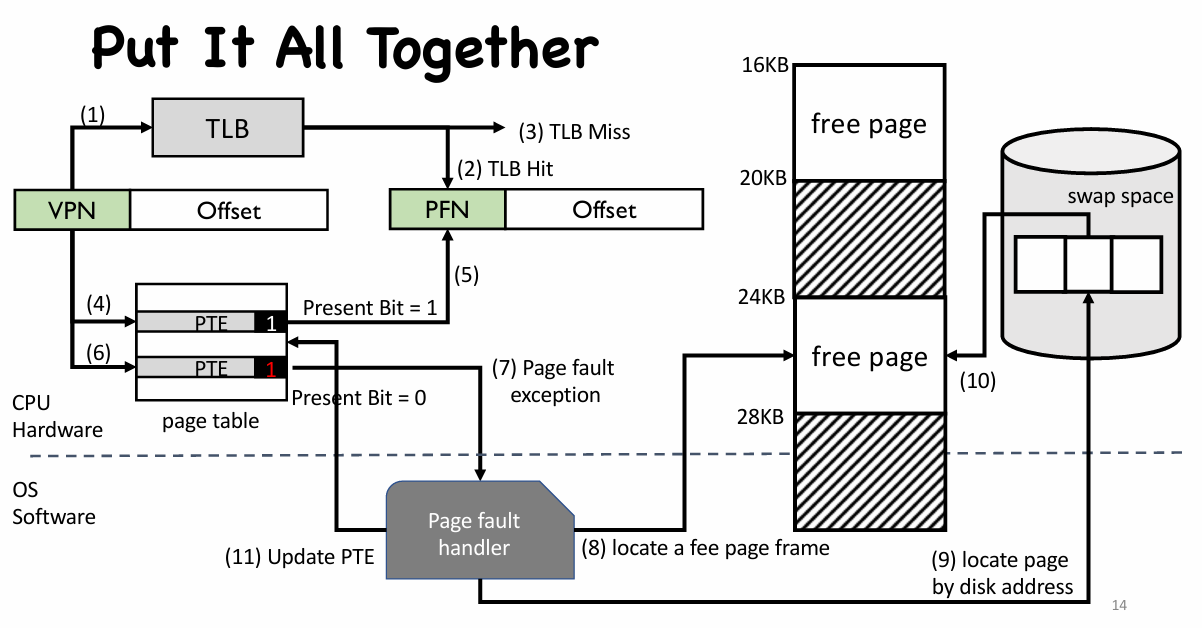

- Using a present bit to indicate whether a page is in physical memory

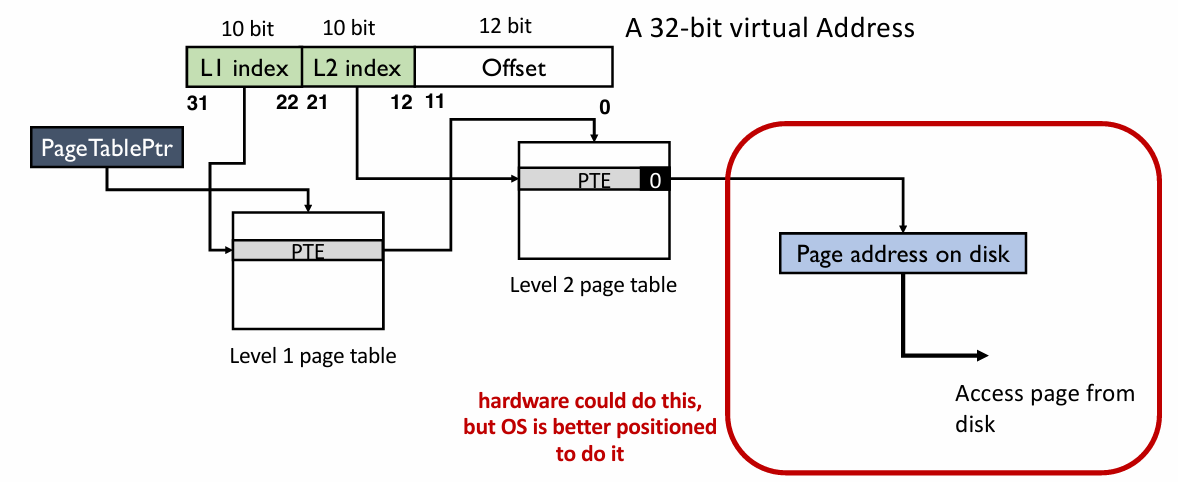

Page Fault

- Present bit = 0 raises a page fault

- OS gets involved in address translation

- Page fault handler

- (1) Find free page frame in physical memory

- (2) Fetch page from disk and store it in physical memory

- After page fault

- Return from page fault exception

- CPU re-execute the instruction that accesses the virtual memory

- No more page fault since present bit is set this time

- TLB entry loaded from PTE

(1) Find free page frame in physical memory

- Find one free page frame from a free-page list

- If no free page, trigger page replacement

- find a page frame to be replaced

- Page replacement policy decides which one to replace

- If page frame to be replaced is dirty, write it back to disk

- Update all PTEs pointing to the page frame

- Invalidate all TLB entries for these PTEs

- find a page frame to be replaced

(2) Fetch page from disk

- Determine the faulting virtual address from register

- Locate the disk address of the page in PTE (where PFN should be stored)

- It is a very natural choice to make use of the space in PTE

- Issues a request to disk to fetch the page into memory

- Wait …… (could be a very long time, context switch!)

- When I/O completes, update page table entry: PFN, present bit

Q: When to Trigger Page Replacement?

- Proactive page replacement usually leads to better performance

- Page replacement even though no one needs free page frames (yet)

- Always reserve some free page frames in the system

- Swap daemon

- background process for reclaiming page frames

- Low watermark: a threshold to trigger swap deamon

- High watermark: a threshold to stop reclaiming page frames

Page Replacement Policy

Effective Access Time (EAT)

$$

EAT=\text{ Hit Rate }\times \text{ Hit Time }+ \text{ Miss Rate }\times \text{ Miss Penalty }

$$

Three types of Cache Misses

- Compulsory Misses:

- Cold-start miss: pages that have never been fetched into memory before

- Prefetching: loading them into memory before needed

- Capacity Misses:

- Not enough memory: must somehow increase available memory size

- One option: Increase amount of DRAM (not quick fix!)

- Another option: If multiple processes in memory: adjust percentage of memory allocated to each one!

- Conflict Misses:

- fully-associative cache (OS page cache) does not have conflict misses

Page Replacement Policies

- Optimal (also called MIN):

- Replace page that will not be used for the longest time

- Lead to minimum page faults in theory

- But OS won’t know about the future.

- FIFO (First In, First Out)

- Throw out oldest page first

- May throw out heavily used pages instead of infrequently used

- RANDOM:

- Pick random page for every replacement

- Pretty unpredictable – makes it hard to make real-time guarantees

- Least Recently Used (LRU):

- Replace page that has not been used for the longest time

- Temporal locality of program

- If a page has not been used for a while, it is unlikely to be used in the near future

- Seem to be practical, huh?

- Least Frequently Used (LFU)

- Replace page that has not been accessed many times

- Spatial locality of program

- if a page has been accessed many times, perhaps it should not be replaced as it clearly has some value. (Like LRU)

Bélády’s Anomaly

When you add memory the miss rate drops in LRU and MIN, but not necessarily for FIFO !

LRU Impl

- Hardware support is necessary

- Update a data structure in OS upon every memory access

- E.g., a timestamp counter for each page frame

- Overhead (LRU 实现需要考虑以下负载)

- One additional memory write for each memory access

- TLB hit does not save the extra memory access

- Scan the entire memory to find the LRU one

- 4GB physical memory has 1 million page frames

- sorting is time consuming

- One additional memory write for each memory access

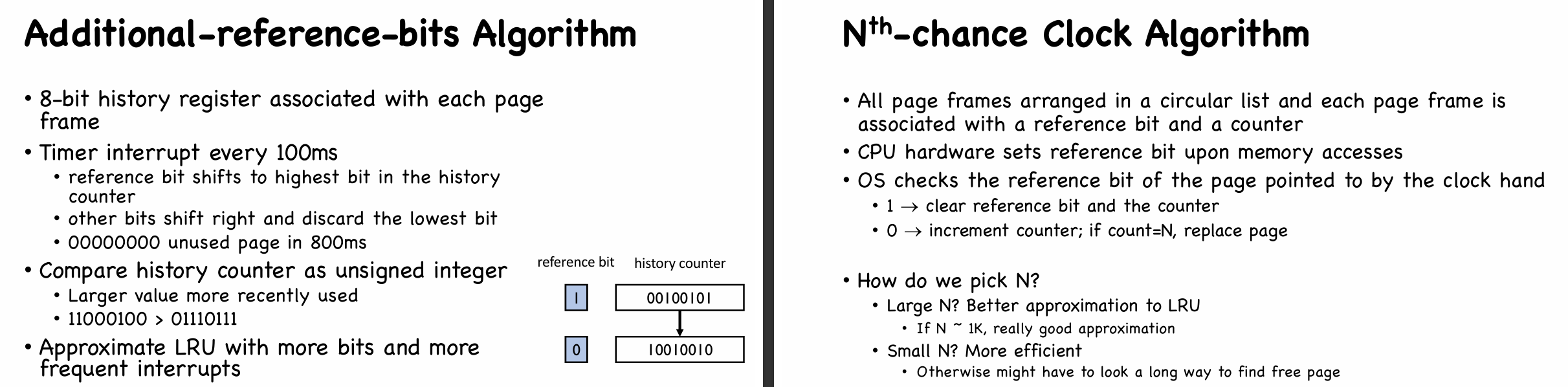

- LRU Approximation with Reference Bit:

- Reference bit

- One reference bit per page frame

- All bits are cleared to 0 initially

- The first time a page is referenced, the reference bit is set by CPU (Can be integrated with page table walk)

- The order of page accesses approximated by two clusters: used and unused pages

- E.g. Clock algorithm(second-chance algorithm), enhanced clock algorithm with dirty bits

- Reference bit

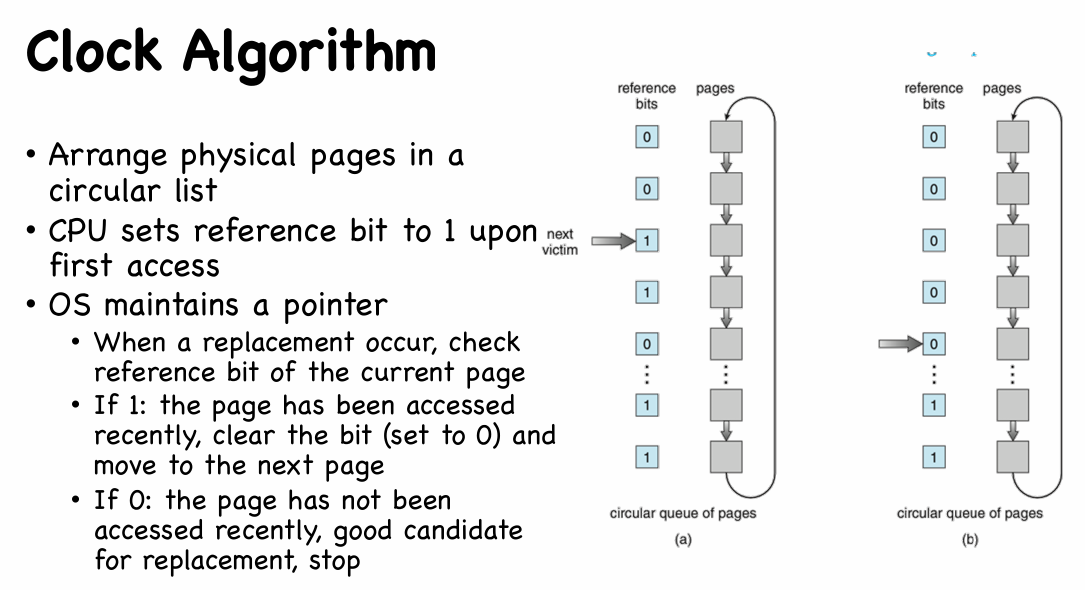

Clock Algorithm

提供了一次“避免被替换”的机会

- Clock Algorithm with Dirty Bit

- dirty bit = 1: the page has recently been modified

- CPU sets dirty bit to 1 upon write access

- When a replacement occurs, OS checks

(ref bit, dirty bit), and selects a candidate page in decreasing order(0, 0)neither recently used nor modified — best page to replace(0, 1)not recently used but modified — not quite as good, because the page will need to be written out before replacement(1, 0)recently used but clean — probably will be used again soon(1, 1)recently used and modified — probably will be used again soon, and the page will be need to be written out to secondary storage before it can be replaced

- Renew: LRU Approximation with Reference Bit and Counter

- Reference bit indicate recent access

- set by CPU hardware, cleared by OS.

- Counter records history of accesses

- Maintained by OS

- Two counter example 👇

- Reference bit indicate recent access

Page Frame Allocation

- How do we allocate memory among different processes?

- Does every process get the same fraction of memory? Different fractions?

- Should we completely swap some processes out of memory?

- Minimum number of pages per process

- Depends on the computer architecture

- How many pages would one instruction use at one time

- x86 only allows data movement between memory and register and no indirect reference

- needs at least one instruction page, one data page, and some page table pages

- Maximum number of pages per process

- Depends on available physical memory

Global vs. Local Allocation

- Global replacement: One process can take a frame from another process

- Local replacement: Each process selects from only its own set of allocated frames

Allocation Algorithms

- Equal allocation:

- Every process gets same amount of memory

- Example: 100 frames, 5 processes $\to$ each process gets 20 frames

- Proportional allocation

- Number of page frames proportional to the size of process

- $s_i =$ size of process $p_i$ and $m =$ total number of frame

- $a_i =$ allocation for $p_i =m\times \frac{s_i}{\sum{s_j}}$

- Priority Allocation:

- Number of page frames proportional to the priority of process

- Possible behavior: If process $p_i$ generates a page fault, select for replacement a frame from a process with lower priority number

Thrashing

The memory demands of the set of running processes simply exceeds the available physical memory

Early OS: pages used actively of a process, and reduce # of process

Modern OS: Out-of-memory killer when memory is oversubscribed (need reboot)

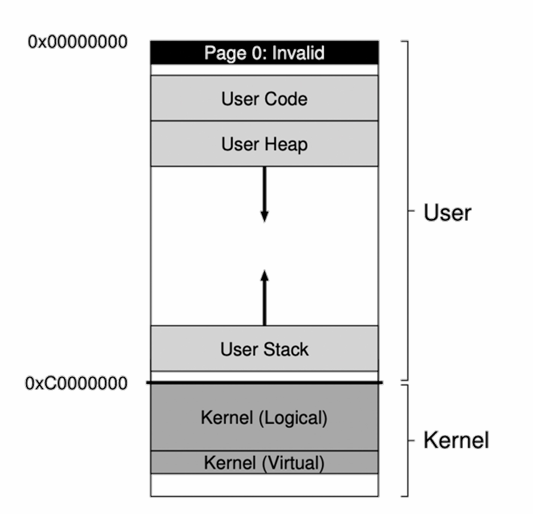

Lec09. Linux Memory Management

Outline

Address Space in Linux

- Each page split into 3:1 (alike) portions, e.g., 3/4 for user mode and 1/4 for kernel space.

Q: Why is kernel memory mapped into the address space of each process?

- No need to change page table (i.e., switch CR3) when trapped into the kernel (no TLB flush)

- Kernel code may access user memory when needed

Aware! —— The kernel memory in each address space is the same

- Linux adds supports to huge page (Linux term)

- Fewer TLB misses

- Applications may need physically continuous physical memory

- Leads to internal fragmentation

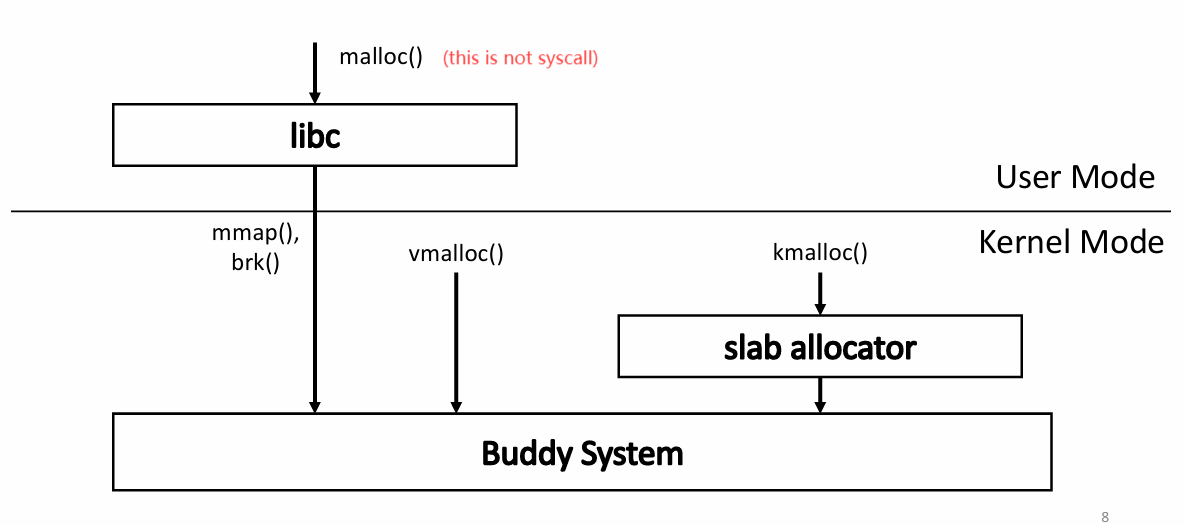

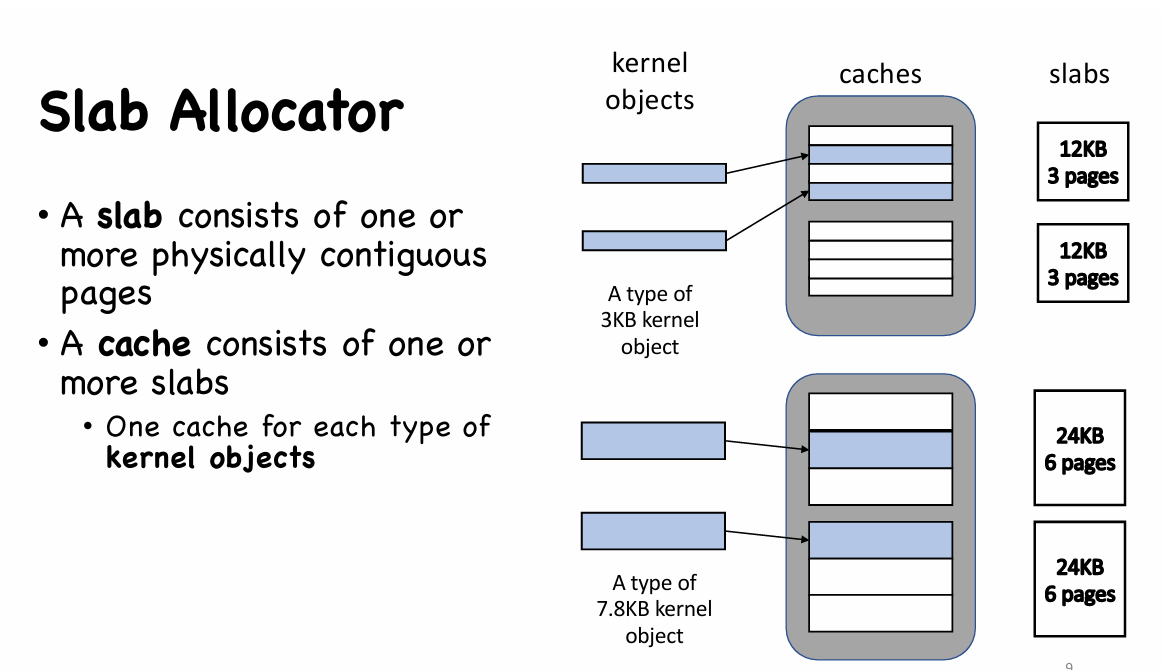

Slab Allocator

- When a slab is allocated to a cache, objects are initialized and marked as free

- A slab can be in one of the following states:

- empty: all objects are free

- partial: some objects are free

- full: all objects are used

- A request is first served by a partial slab, then empty slab, then a new slab can be allocated from buddy system (buddy system 会介绍如何被分配到一个全新的 slab 中)

- No memory is wasted due to fragmentation

- when an object is requested, the slab allocator returns the exact amount of memory required to represent the object

- Objects are packed tightly in the slab

- Memory requests can be satisfied quickly

- Objects are created and initiated in advance

- Freed object is marked as free and immediately available for subsequent requests

- Later Linux kernel also introduces Slub allocator and Slob allocators.

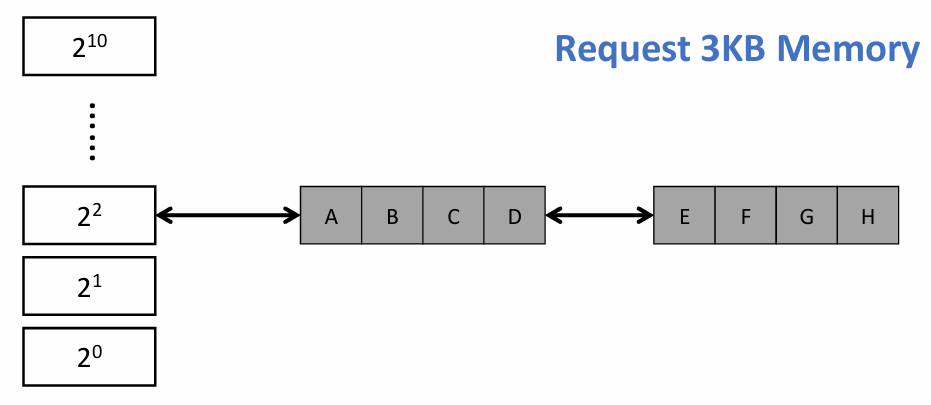

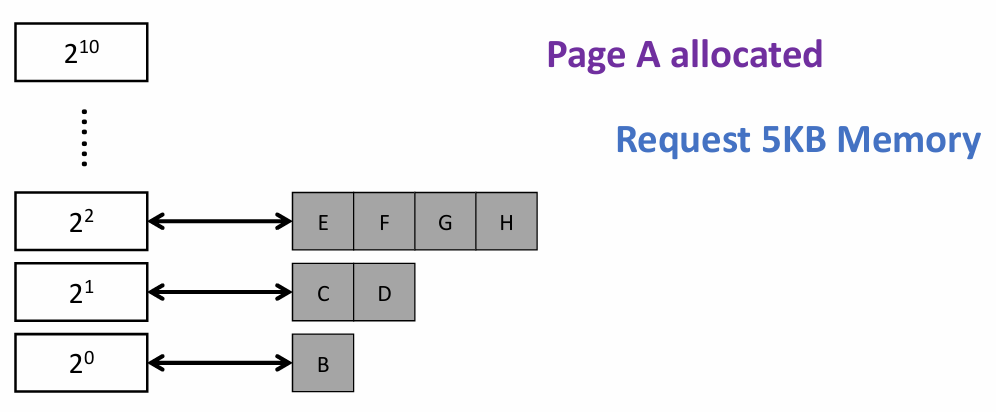

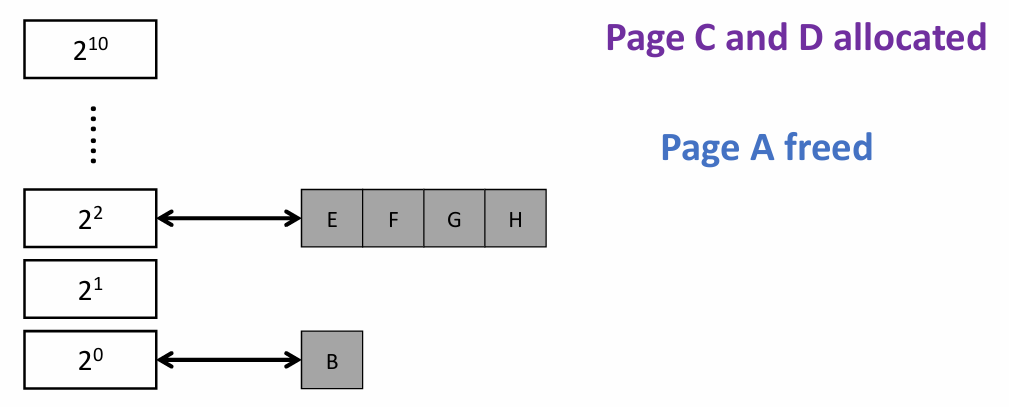

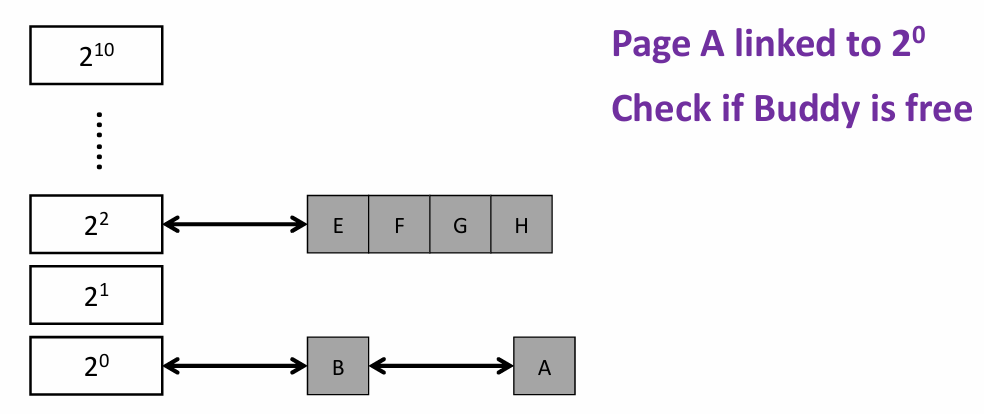

Buddy System

- Free physical memory is considered big space of size $2^N$ pages

- Allocation: the free space is divided by two until a block that is big enough to accommodate the request is found

- a further split would result in a space that is too small

- Free: the freed block is recursively merged with its buddy

- Two buddy blocks have physical addresses that differ only in 1 bit

- e.g. following example: page size = 4 KB

|

|

|

|

|

Note that two buddy system differ at bit i (where they separate, e.g., A and B at the lowest bit) on their PFN |

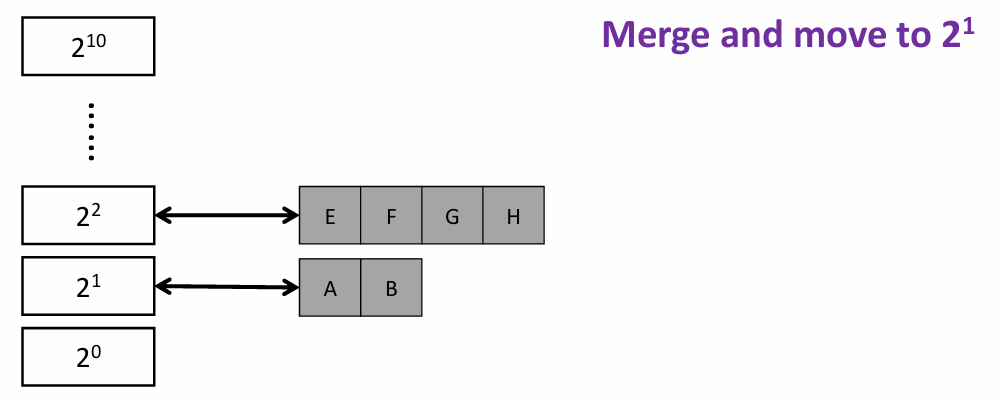

Lec10. I/O

Outline

- I/O Management & View of Device

- Basic I/O: Polling

- Efficient I/O: Interrupts

- Data Movement

- Device Driver

I/O Management & View of Device

- Challenges of I/O management

- Diverse devices: each device is slightly different

- How can we standardize the interfaces to these devices?

- Unreliable device: media failures and transmission errors

- How can we make them reliable?

- Unpredictable and slow devices

- How can we manage them if we do not know what they will do or how they will perform?

- Diverse devices: each device is slightly different

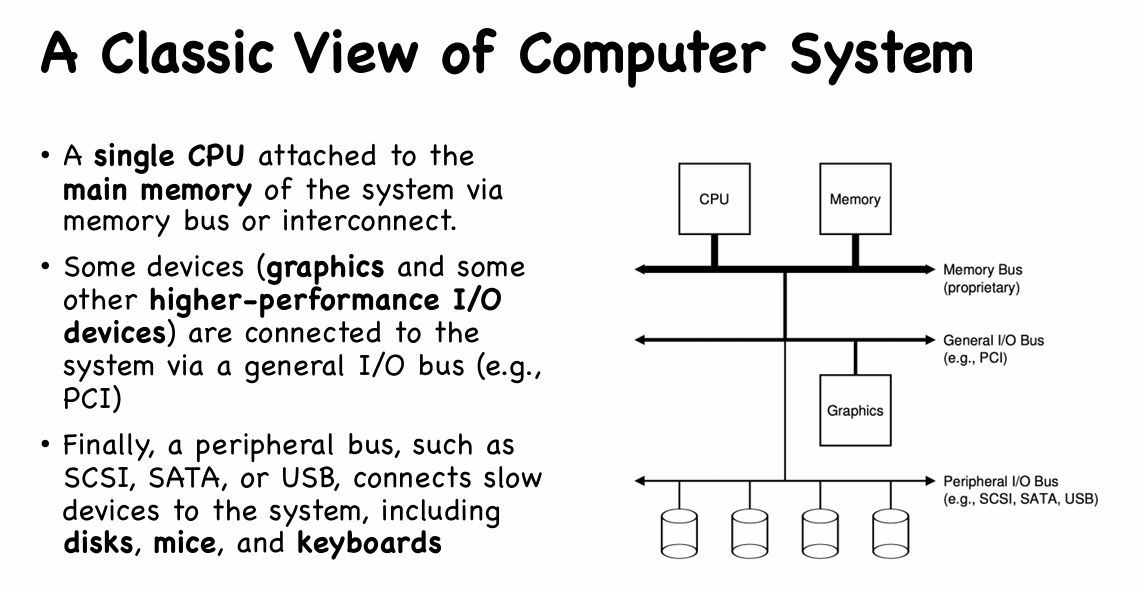

A Canonical View of Devices

- Interface

- The hardware interface a device present to the rest of the system

- Status registers: check the current status of the device

- Command register: tell the device to perform a certain task

- Data register: pass data to the device or get data from the device.

- Internal structures

- Implementation of the abstract of the device

Basic I/O: Polling

- OS waits until the device is ready to receive a command by repeatedly reading the status register;

- OS sends some data down to the data register;

- OS writes a command to the command register;

- OS waits for the device to finish by again polling it in a loop, waiting to see if it is finished.

- Issues

- frequent checking the status of I/O devices

- inefficient and inconvenient

- Polling wastes CPU time waiting for slow devices to complete its activity

- If CPU switches to other tasks, data may be overwritten (CPU 内数据改变,导致写入设备的数据出错)

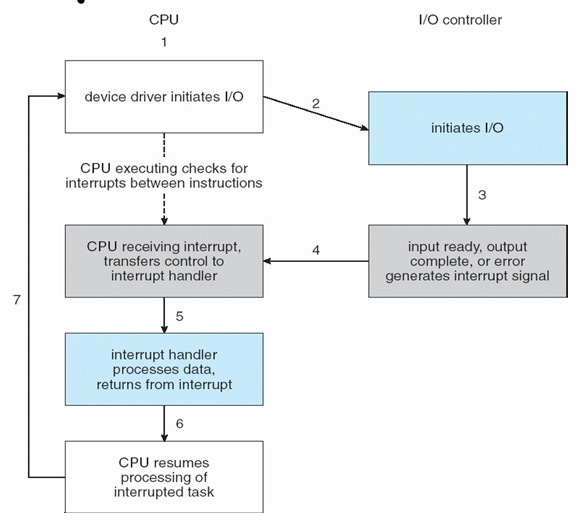

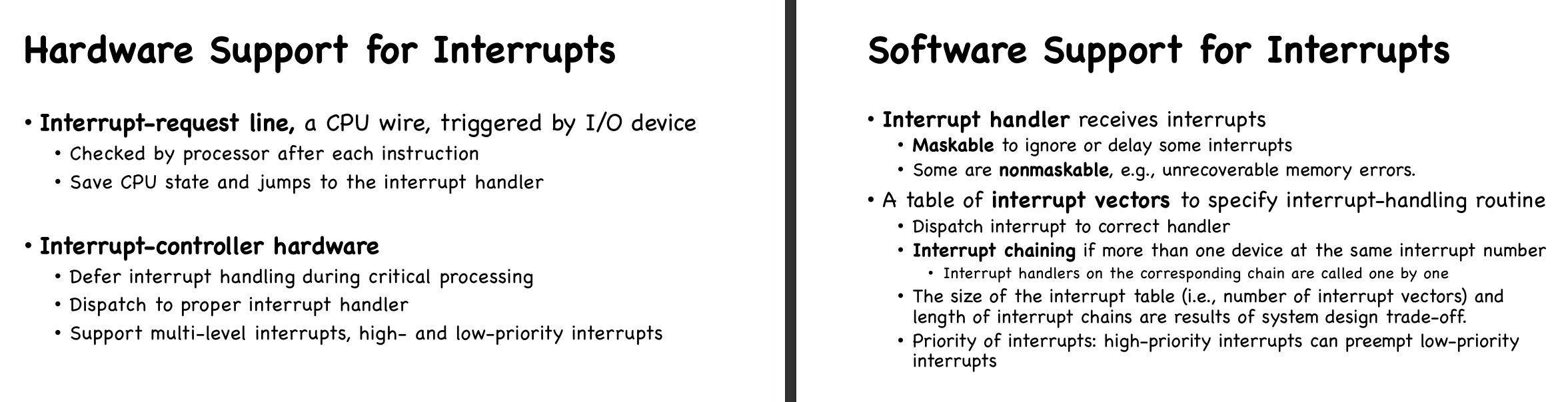

Efficient I/O: Interrupts

- Idea

- Put the calling process to sleep, and context switch to another task.

- When the device is finally finished with the operation, it will raise a hardware interrupt, causing the CPU to jump into the OS at a predetermined interrupt handler

- Comparison

- Polling works better for fast devices

- Data fetched with first poll

- Interrupt works better for slow devices

- Context switch is expensive

- Polling works better for fast devices

- Hybird approach if speed of the device is not known or unstable

- Polls for a while

- Then use interrupts

Others related to Interrupt:

System call is made by executing a special instruction called software interrupts to trigger kernel to execute request

Multi-CPU systems can process interrupts concurrently

Data Movement

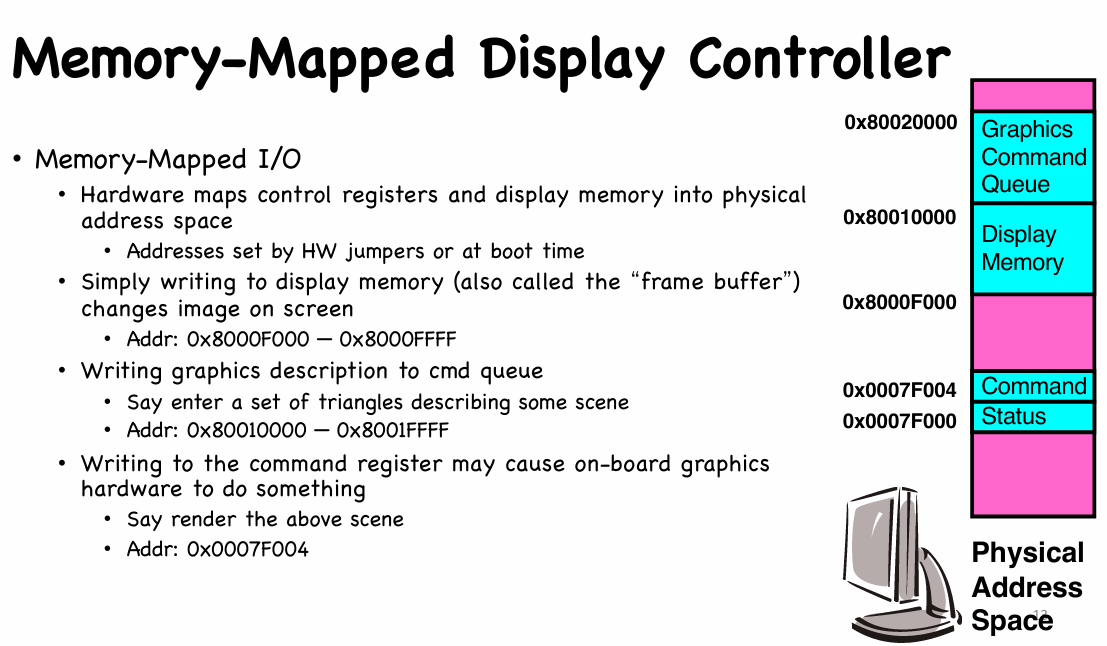

Programmed I/O

- Explicit I/O instructions

- in/out instructions on x86:

out 0x21,AL - I/O instructions are privileged instructions

- in/out instructions on x86:

- Memory-mapped I/O

- Registers/memory appear in physical address space

- I/O accomplished with load and store instructions

- I/O protection with address translation

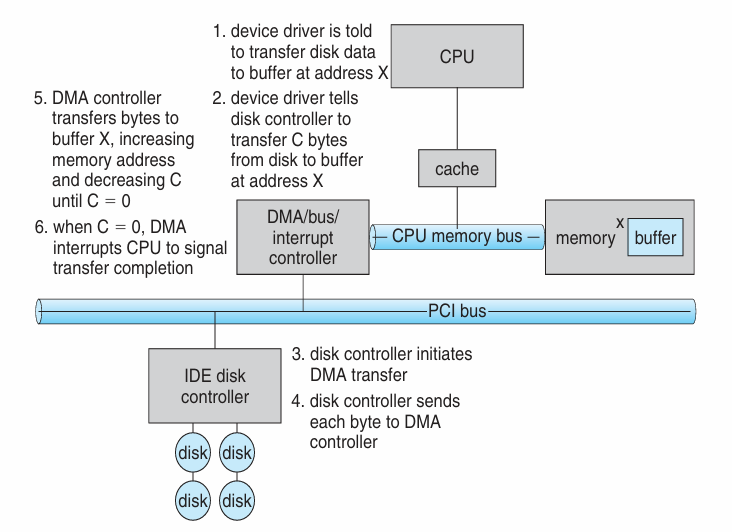

DMA

Def. Direct Memory Access

- DMA is used to avoid programmed I/O for large data movement

- Programmed I/O (PIO): when CPU is involved in data movement

- PIO consumes CPU time

- bypasses CPU to transfer data directly between I/O device and memory

- OS writes DMA command block into memory

- Source and destination addresses

- Read or write mode

- Count of bytes

- Writes location to DMA controller

- Bus mastering of DMA controller – grabs bus from CPU

- Cycle stealing from CPU but still much more efficient

- When done, interrupts to signal completion

Device Driver

Def. Device-specific code in the kernel that interacts directly with the device hardware, which support a standard, internal interface.

Special device-specific configuration supported with the ioctl() system call

- Two pieces of Device Driver:

- Top half: accessed in call path from system calls

- implements a set of standard, cross-device calls like

open(),close(),read(),write(),ioctl(),strategy(). - This is the kernel’s interface to the device driver

- Top half will start I/O to device, may put thread to sleep until finished

- implements a set of standard, cross-device calls like

- Bottom half: run as interrupt routine

- Gets input or transfers next block of output

- May wake sleeping threads if I/O now complete

- Top half: accessed in call path from system calls

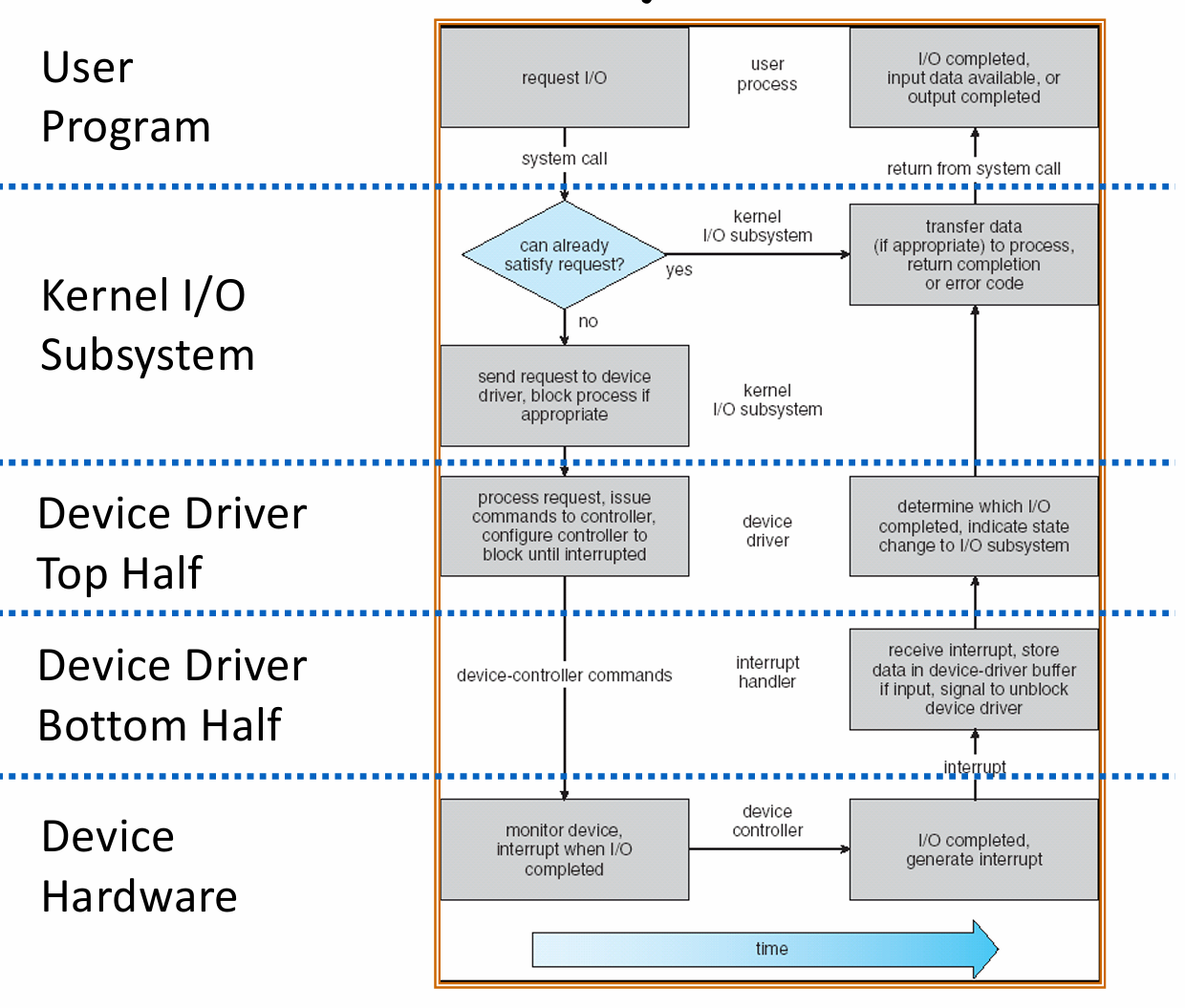

Life Cycle of an I/O Request

Different types of device

|

|

Lec11. Storage

Outline

- Storage Devices

- Disk Scheduling

Storage Devices

- Magnetic disks

- Storage that rarely becomes corrupted

- Large capacity at low cost

- Block level random access

- Poor performance for random access

- Better performance for sequential access

- Flash memory

- Storage that rarely becomes corrupted

- Capacity at intermediate cost (5-20x disk)

- Block level random access

- Good performance for reads; worse for random writes

Concepts for Magnetic Disk

- Sector: Unit of Transfer

- Ring of sectors form a track

- Stack of tracks form a cylinder (disk)

- Heads (磁头) position on cylinders (to read data)

- Disk Tracks $\approx 1\mu m$ wide

- Separated by unused guard regions

- avoid corrupted in writes

Calculation: Time of read/write

Three types of delay

-

Seek time: position the head/arm over the proper track

-

Rotational latency: wait for desired sector to rotate under r/w head

-

Transfer time: transfer a block of bits (sector) under r/w head

-

Assumptions:

- Ignoring queuing and controller times for now

- Avg seek time of 5ms,

- 7200RPM $\Rightarrow$ Time for rotation: 60000 (ms/minute) / 7200(rev/min) $\cong$ 8ms

- Transfer rate 4MByte/s, sector size 1 Kbyte $\Rightarrow$ 1024 bytes / 4 $\times 10^{6}$(bytes/s) $=$256 $\times 10^{-6}$ sec $=$ 0.256 ms

-

Read from random place of disk: use avg rot. latency:

- Seek (5ms) + Rot. Delay (4ms) + Transfer (0.26ms) $\approx 10ms$ for a sector

Now Magnetic Disks are gradually replaced by SSDs(Solid State Disks)

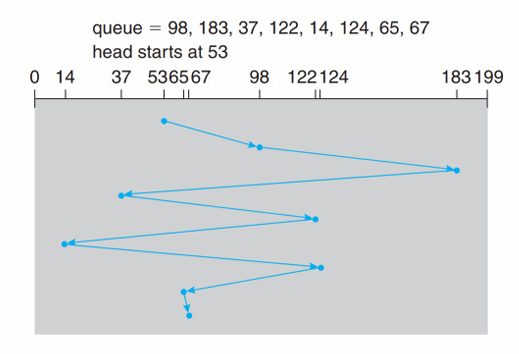

Disk Scheduling

OS should think how to use hardware efficiently?

Try to reduce seek time !

How to minimize the total head movement distance?

- Given a sequence of access cylinders in the HDD

- 98, 183, 37, 122, 14, 124, 65, 67

- Head point: 53

- Pages: 0 ~ 199

See how different scheduling algorithms work.

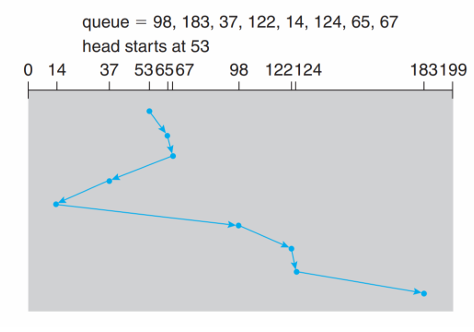

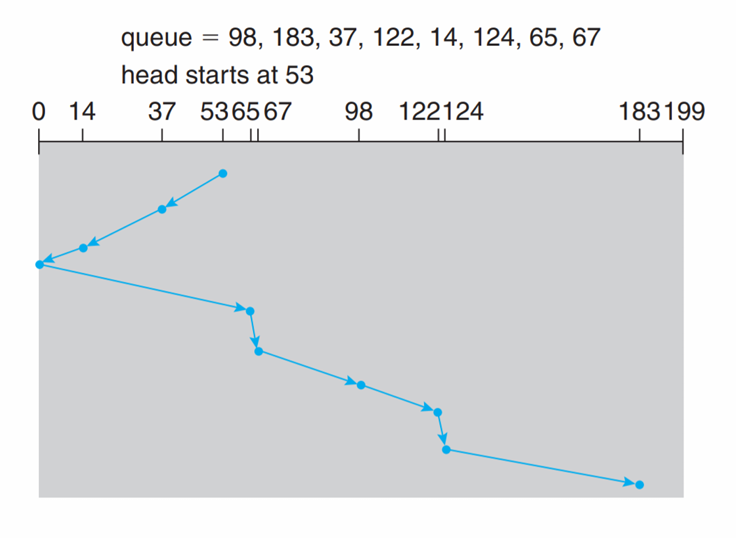

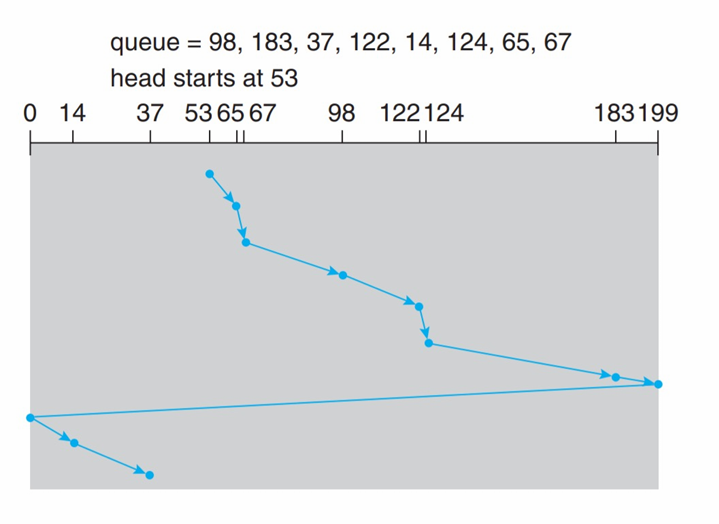

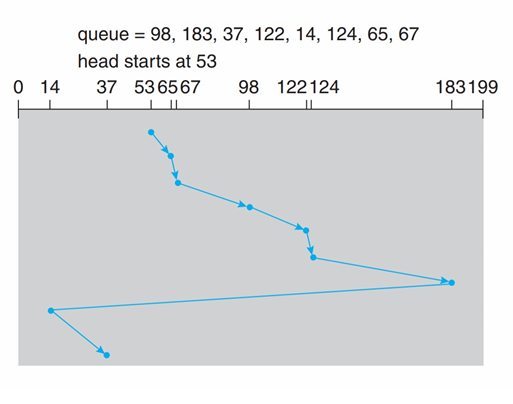

FIFO (First in First out) |

SSTF (Shortest Seek Time First) |

SCAN (elevator algo') |

C-SCAN |

LOOK, C-LOOK |

- Explanations

- In C-SCAN, when the head move to one end (e.g. 199), it immediately turn to another end (e.g. 0), and won’t cost the seek time (no 199 - 0)

- The LOOK scheduling is improvement based on SCAN, and C-LOOK based on LOOK and C-SCAN. Both of the LOOK scheduling cost extra “look” time, but they have better performance (the head no need to go to the end)

- C-LOOK only have one-direction service request, but it have best performance among these schedulings.

Lec12. File System

Outline

- File System Basic

- Contiguous Allocation

- Linked Allocation

- iNode Allocation

- Ext 2/3/4

File System Basic

Def. Layer of OS that transforms block interface of disks (or other block devices) into Files, Directories, etc.

- File System Components

- Naming: Interface to find files by name, not by blocks

- Disk Management: collecting disk blocks into files

- Protection: Layers to keep data secure

- Reliability/Durability: Keeping of files durable despite crashes, media failures, attacks, etc.

- Directory

- A hierarchical structure.

- Each DIR’ entry is a collection of

- Files

- Directories

- a link to another entry

- Each has a name and attributes

- files have data

- Links (hard links, 类似快捷方式) make it a DAG (有向无环图), not just a tree

- Softlinks (类似副本) are another name for an entry

- File

- Named permanent storage.

- Contains

- Data

- Metadata (Attributes)

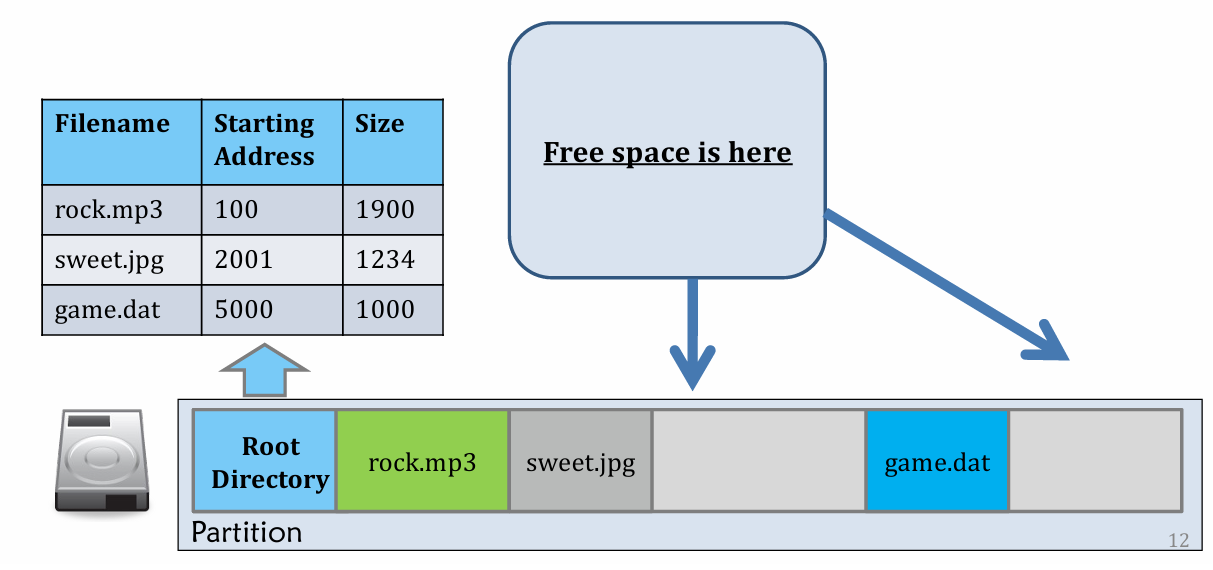

Contiguous Allocation

Easy to understand.

- Good for locate file and delete file

- Bad for create!

- External Fragmentation take response for it.

- Defragmentation process may help, but it’s expensive (data movement on disk)!

Before |

After |

- Usage today

- ISO 9660 (光盘映射文件)

- CV-ROM (no writing)

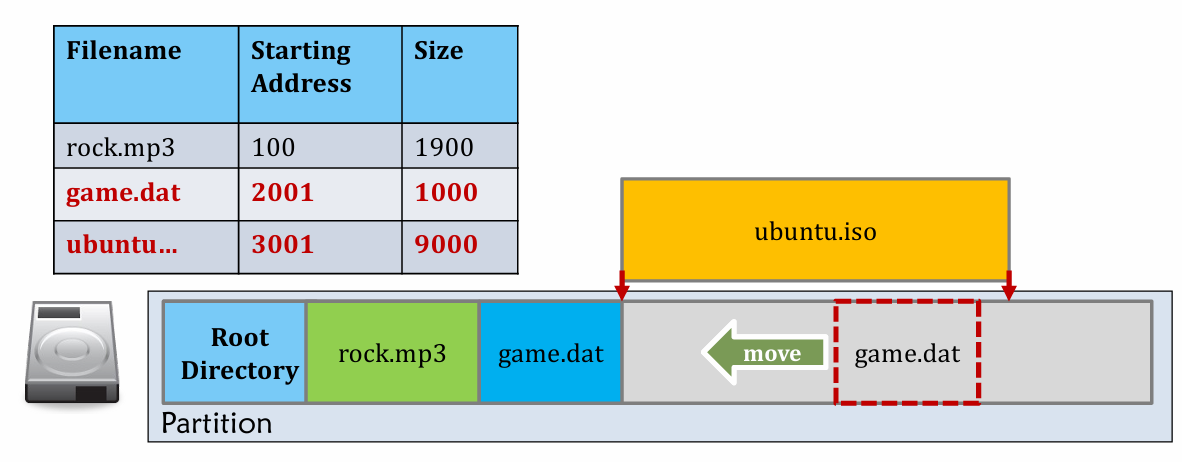

Linked Allocation

Step (1). Chop the storage device and data into equal sized blocks.

Step (2). Fill the empty space in a block-by-block manner.

Step (3). Leave 4 bytes from each block as “pointer” to next block of the same file. But still keep the file size in root directory table (facilitates ls -l etc. which lists file size)

Comparison to contiguous allocation

| Contiguous alloc | Linekd alloc | |

|---|---|---|

| Fragmentation | External Fragmentation | Internal Fragmentation (not all files are multiple of block size) |

| Random access | good performance | Bad performance(e.g. if I want 900th block, I have to go through previous 899.) |

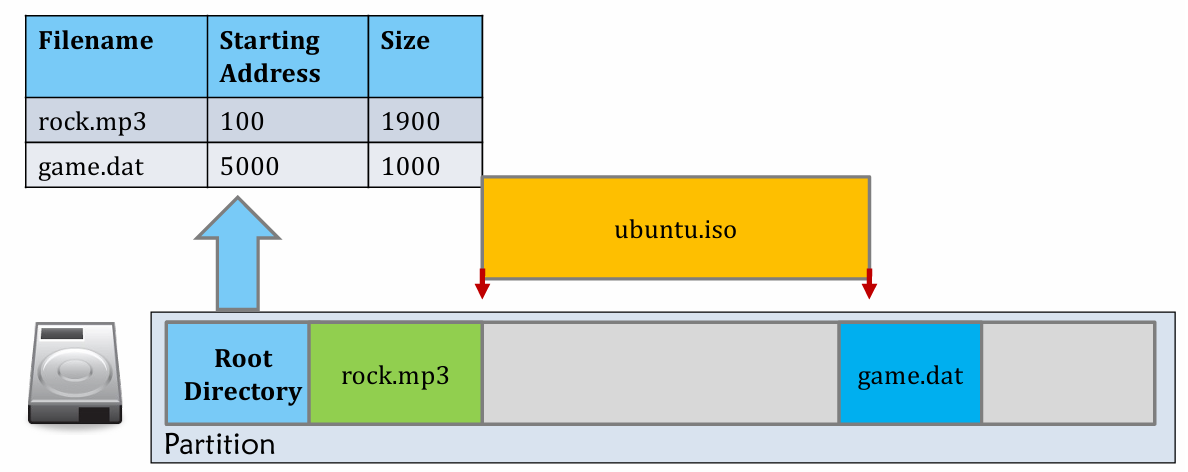

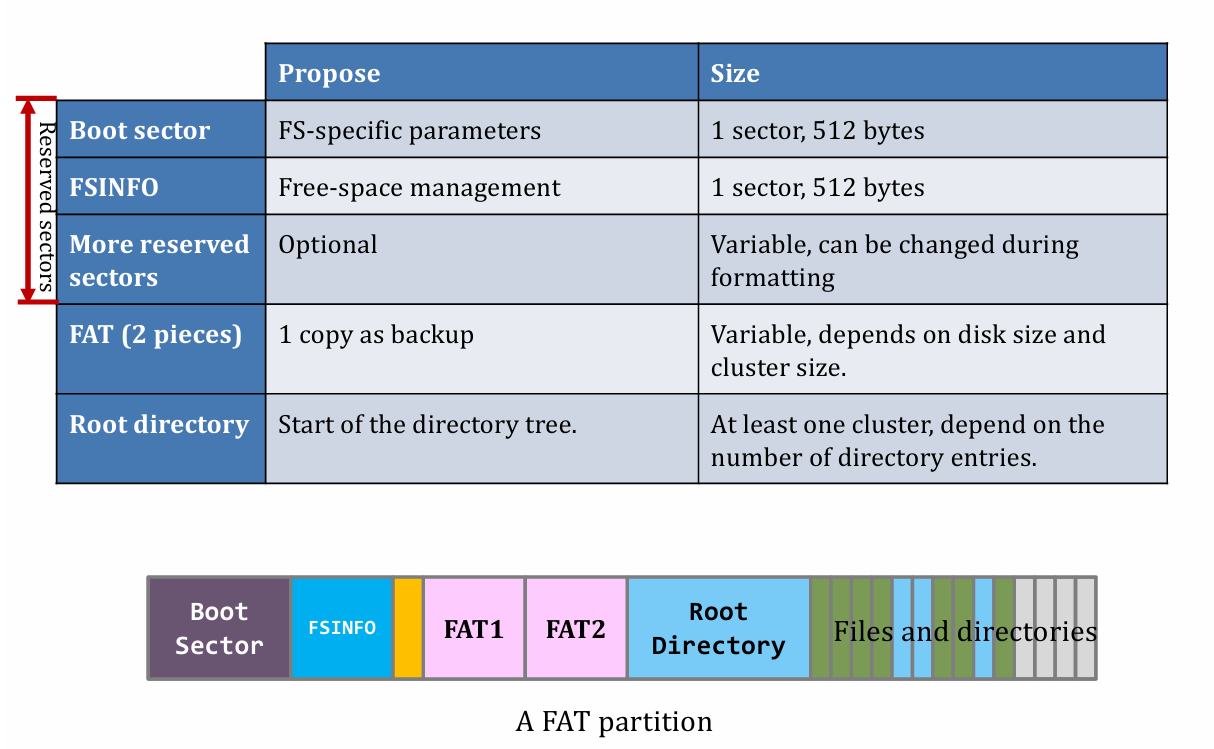

FAT

- Solution to the Poor performance of random access:

- File Allocation Table (FAT)

- Turning the 4 bytes at the head of each block to a table besides Root Directory

- can only search for the table to get random access.

- In DOS, a block is called a “cluster”.

- The cluster address length equals to the block address

- Calculation: Given block size (e.g. 32 KB) and block address (e.g. 28 bits), we can know about the File System size

- $fss=32\times 2^{10} \times 2^{28}=2^{43}\text{ Bytes}=8\text{ TB}$

- What is more complex 👇

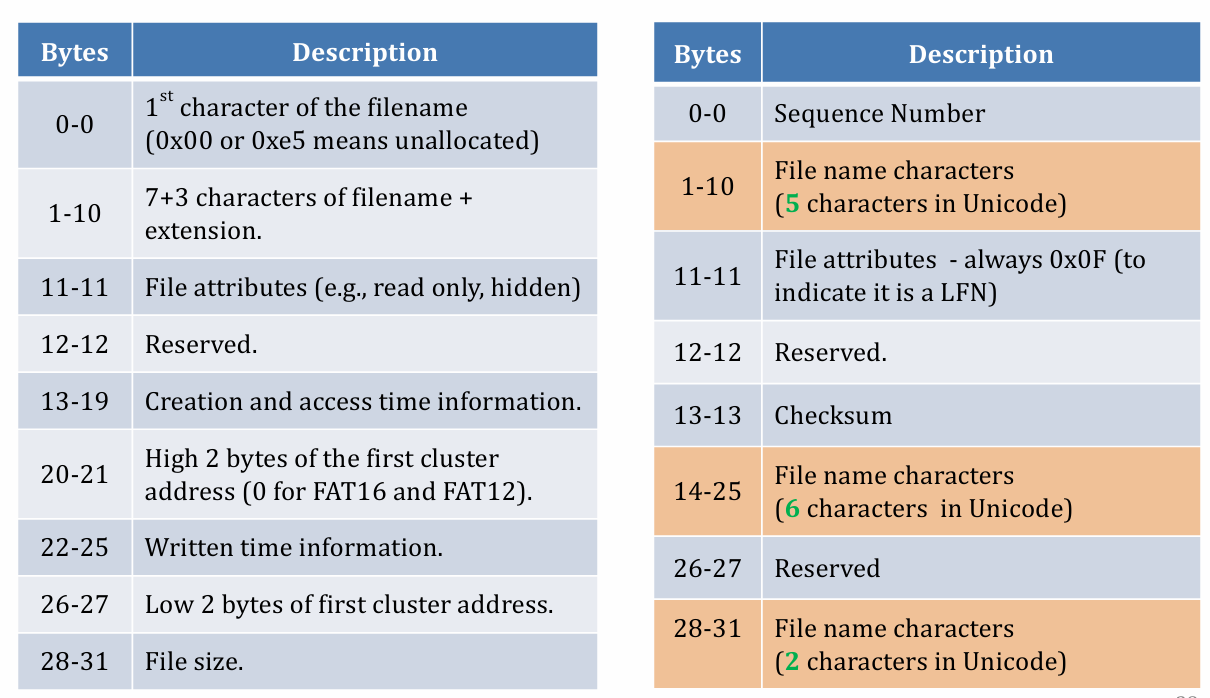

Header of file name

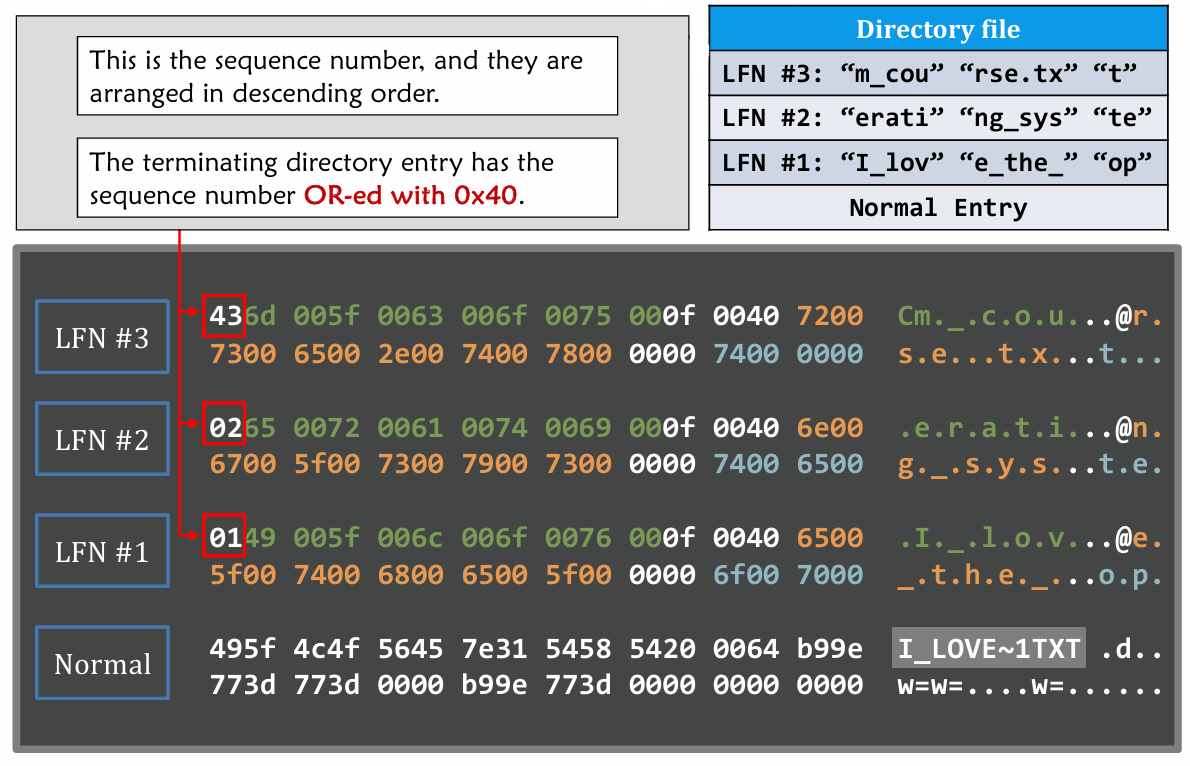

- Compare format difference from Normal DIR entry and LFN (Long File Name) entry

How does LFN really work when a long file name occur ? 👇

About FAT reading, appending and deleting files

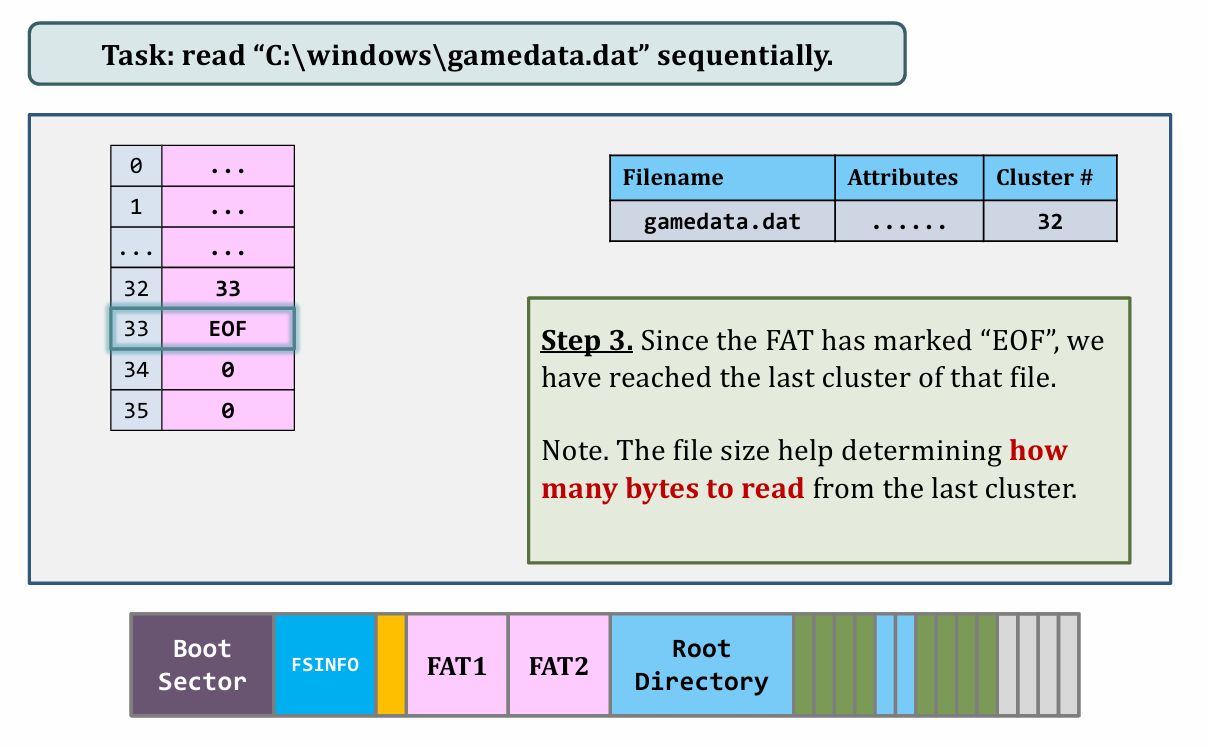

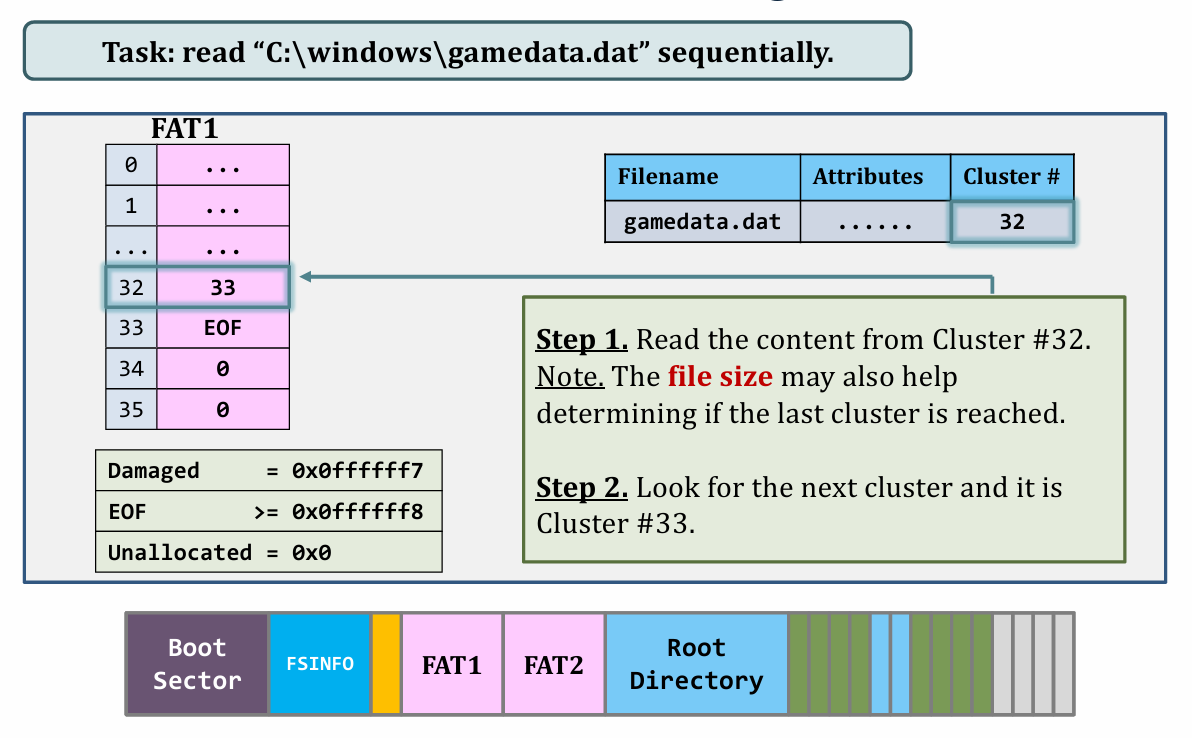

I. Reading

|

|

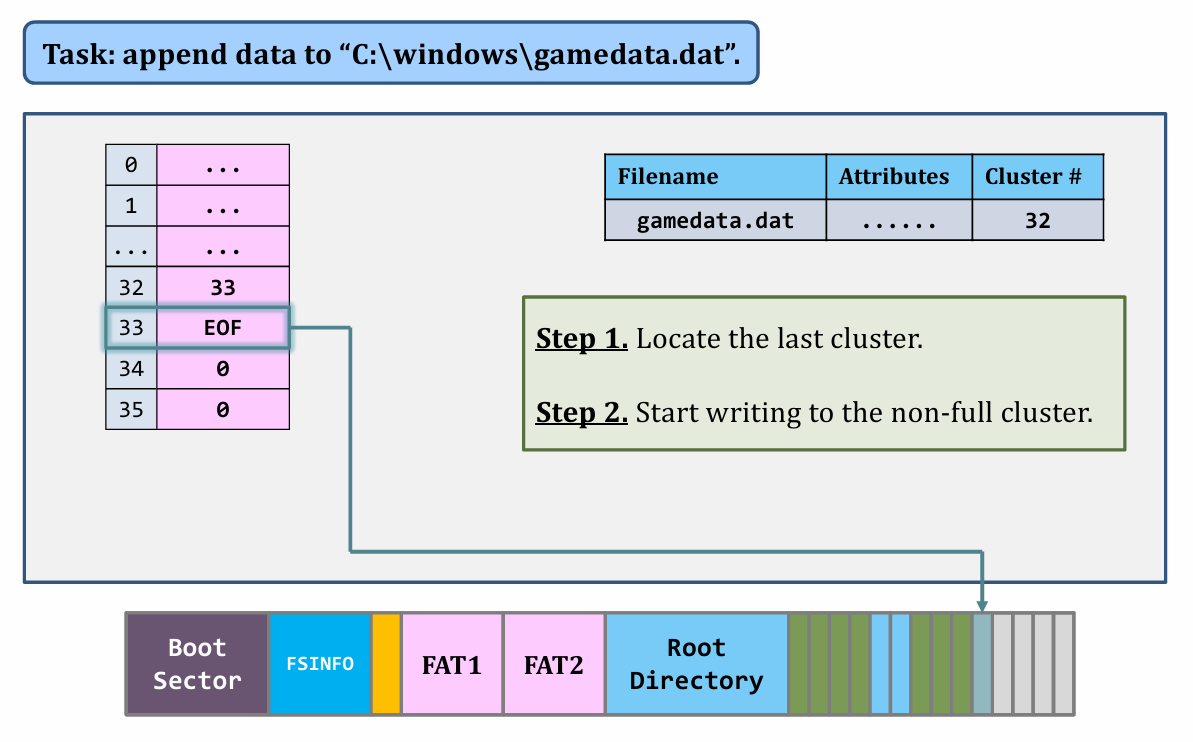

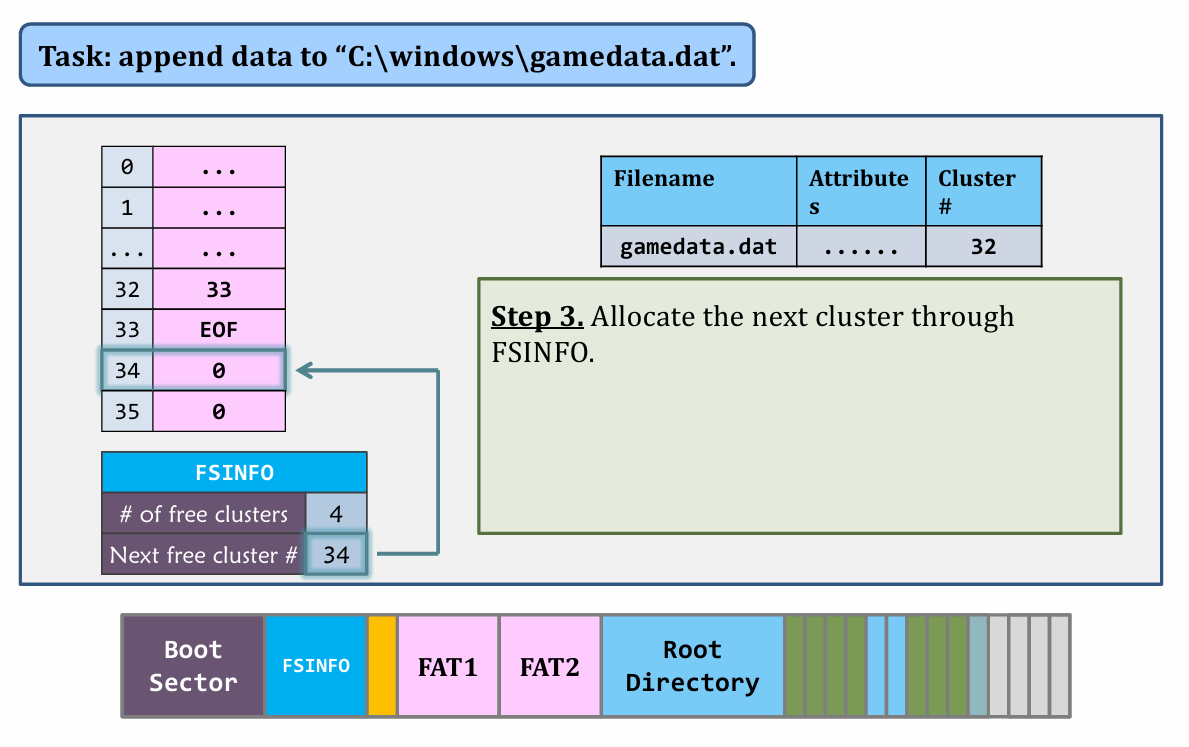

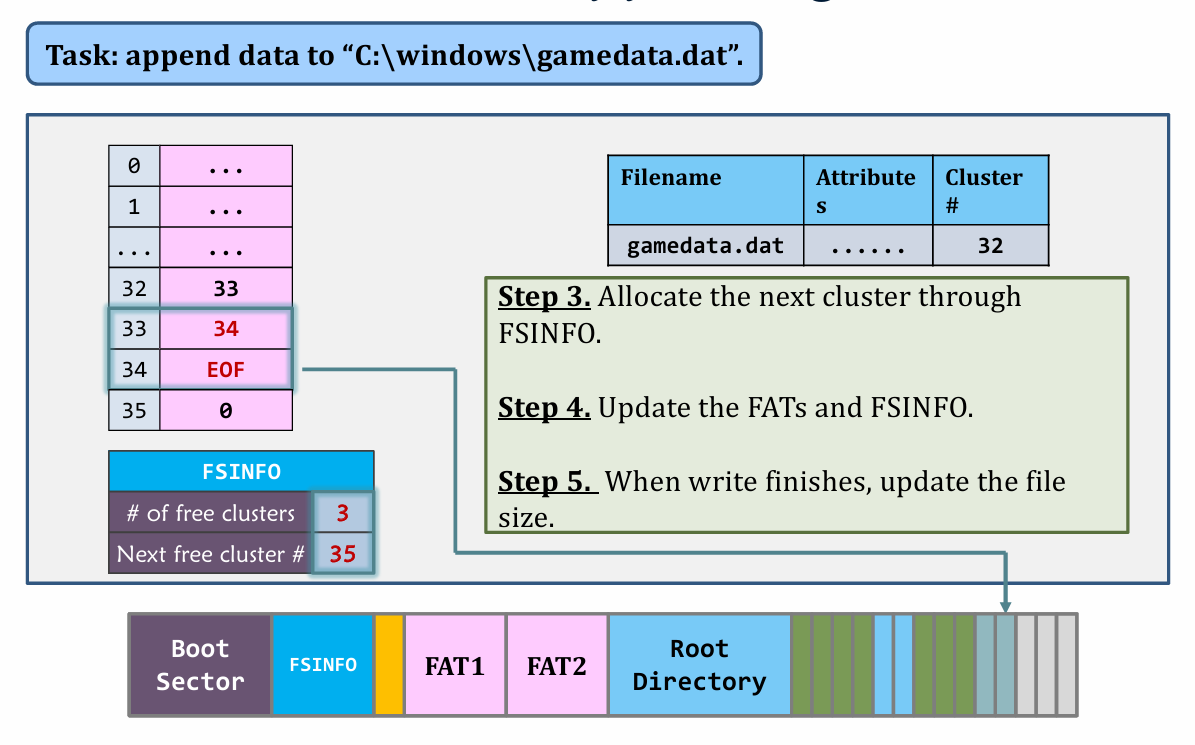

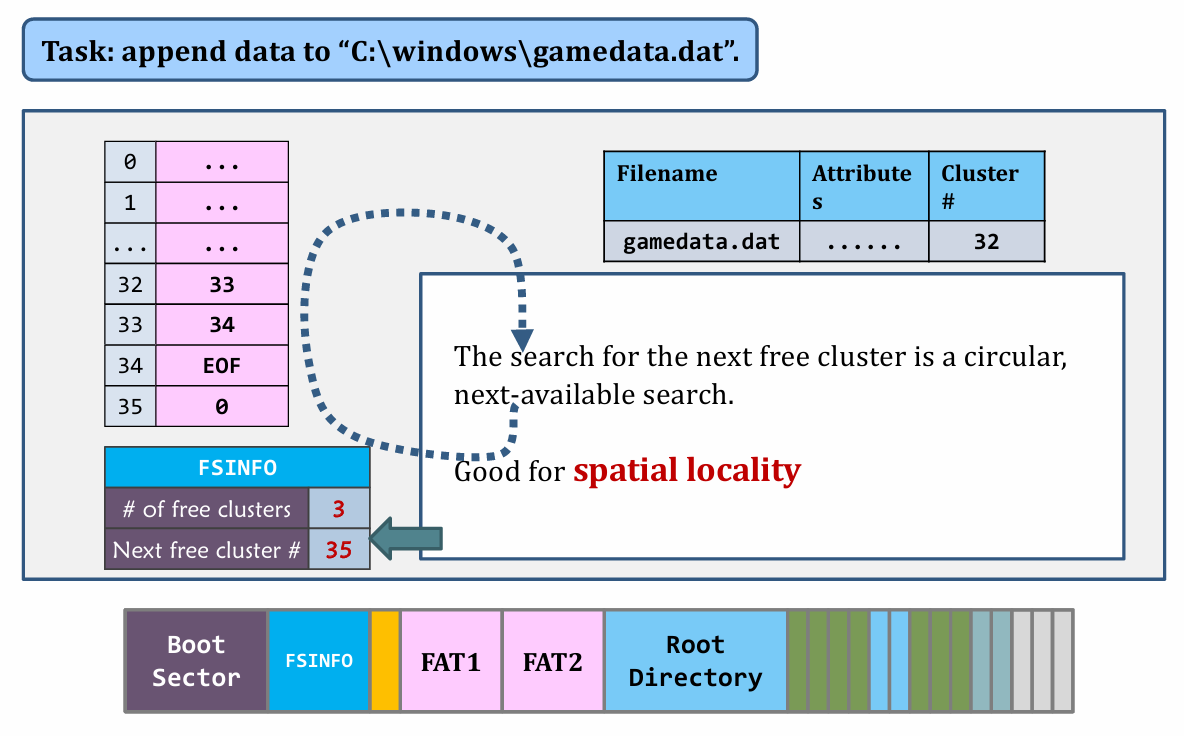

II. Appending data

|

|

|

|

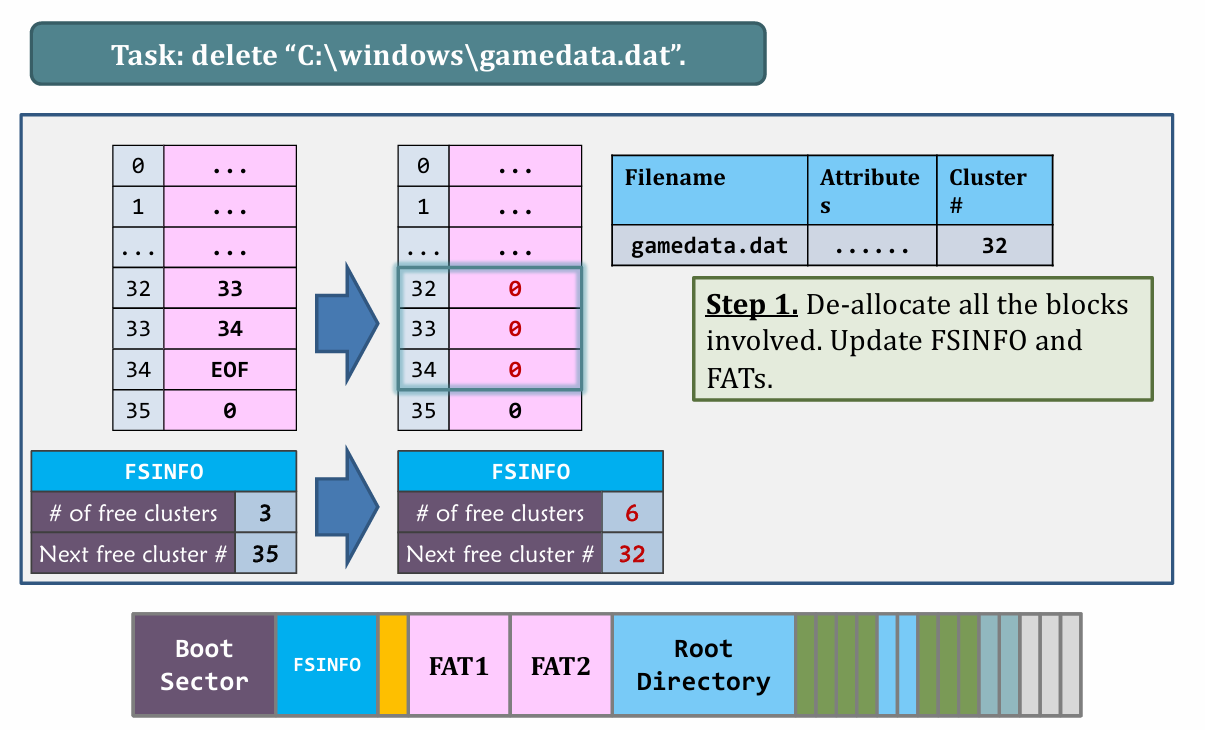

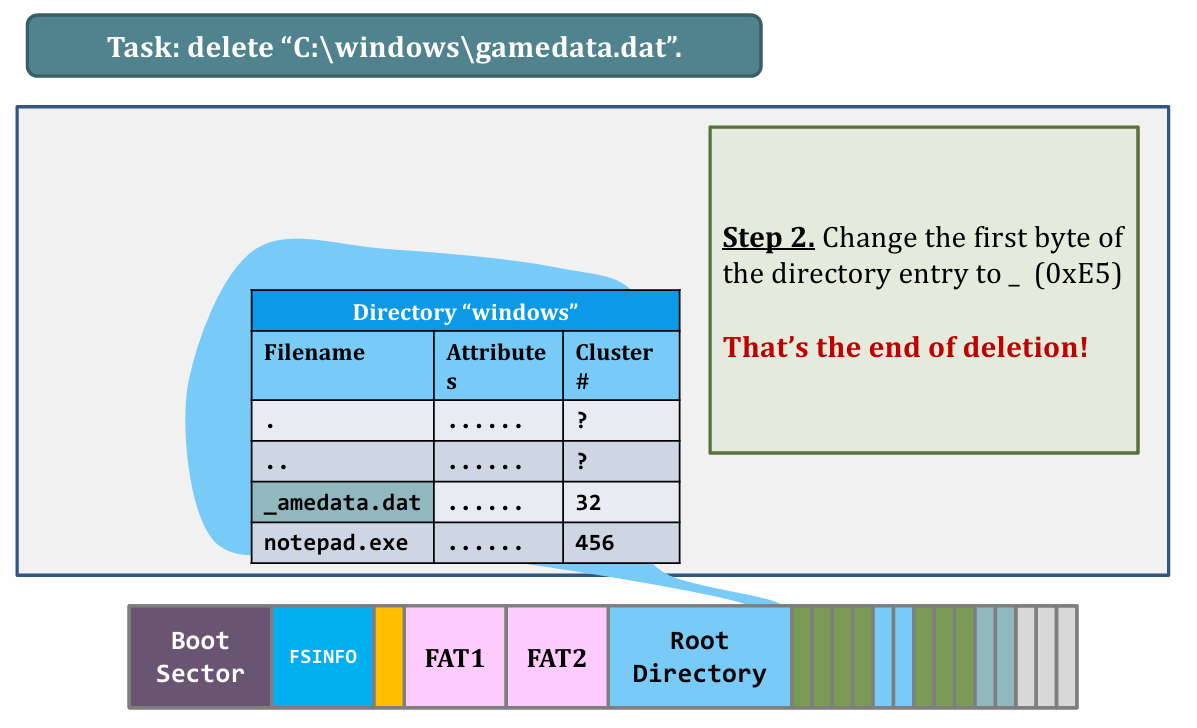

III. Deleting files

|

|

- Lazy delete

- “Deleted data” persists until the de-allocated clusters are reused.

- Efficient but insecure (in multi-user system).

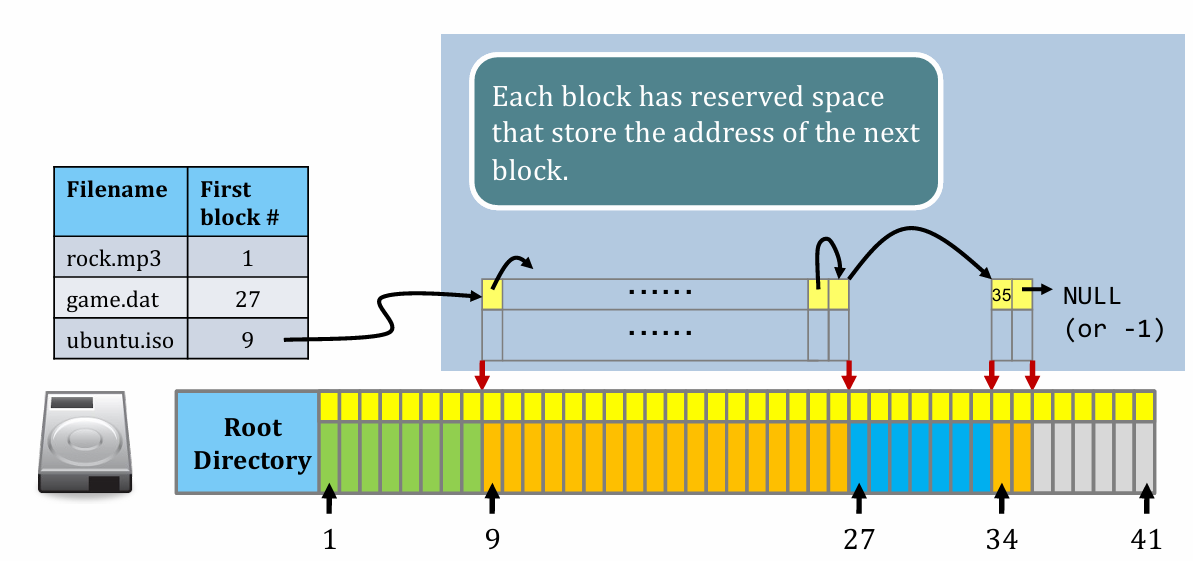

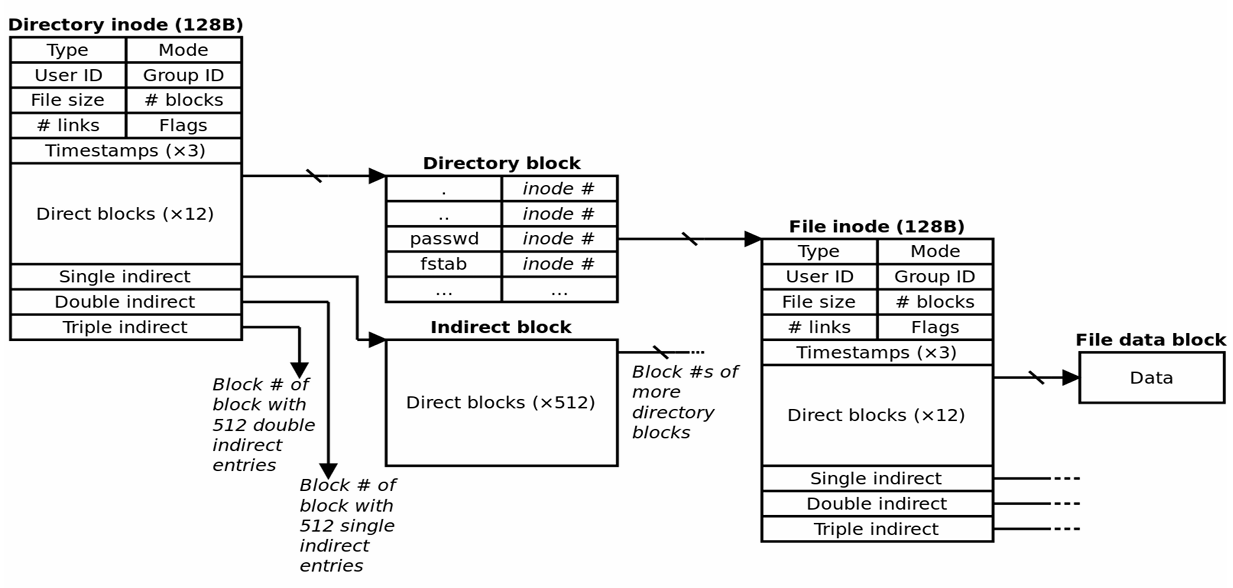

iNode

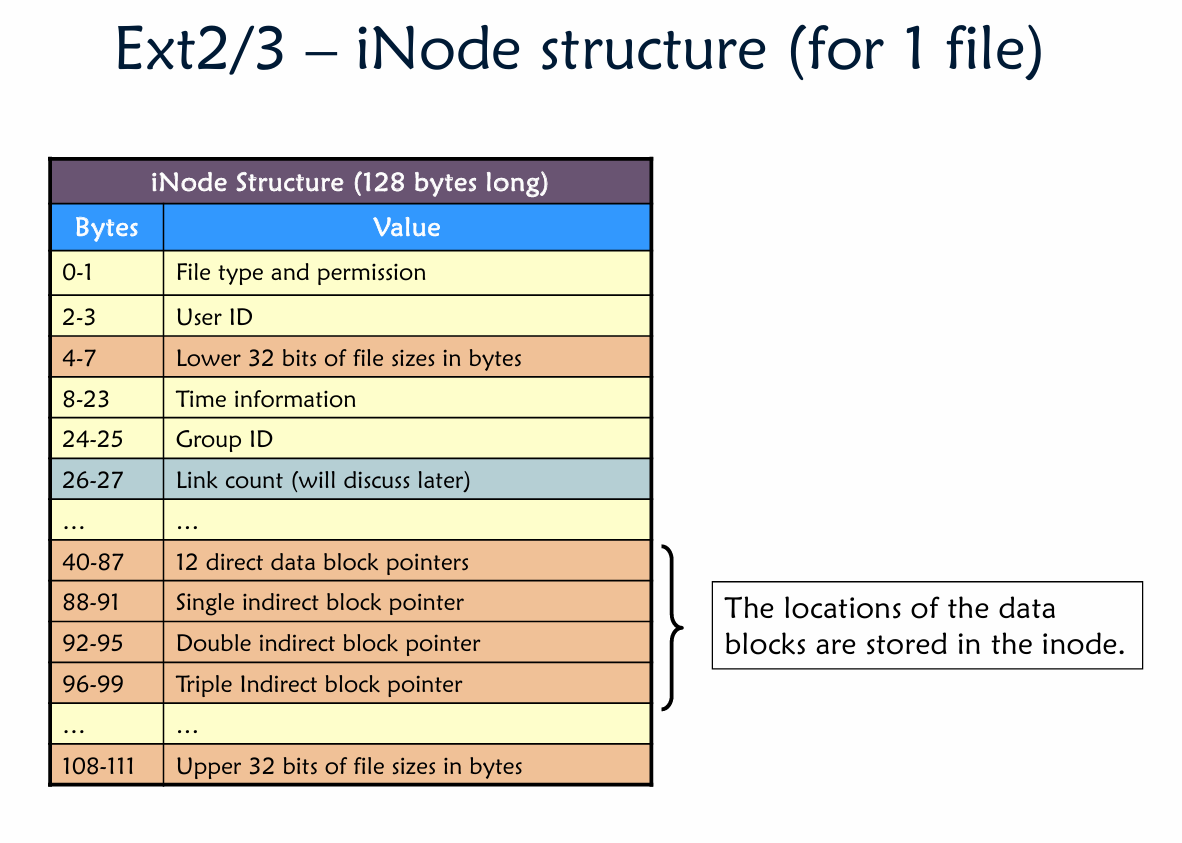

- Original iNode format appeared in BSD 4.1

- Berkeley Standard Distribution Unix

- Similar structure for Linux Ext2/3

- File Number is index of iNode arrays

- Multi-level index structure

- Great for little and large files

- Unbalanced tree with fixed sized blocks

- Metadata associated with the file

- Rather than in the directory that points to it

- Scalable directory structure

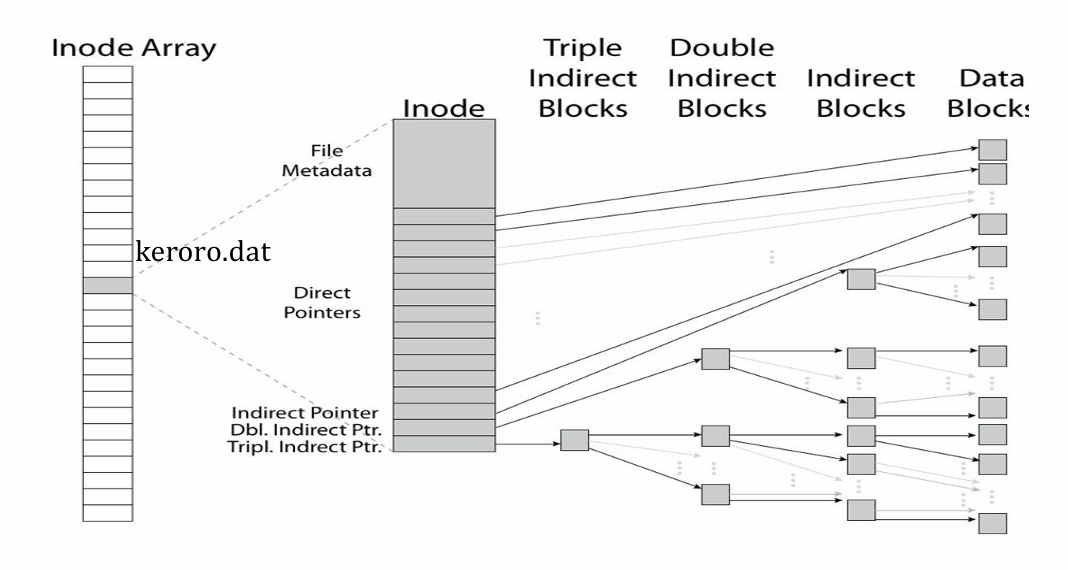

不同于 FAT 将所有文件指针放在一起,iNode 的单位是文件/文件夹。每个文件(夹)对应一个 iNode。(格式见下图)

而索引(存储)方式则是用一个 iNode array 进行存储

而指针采用非平衡树状数据结构(如下图)

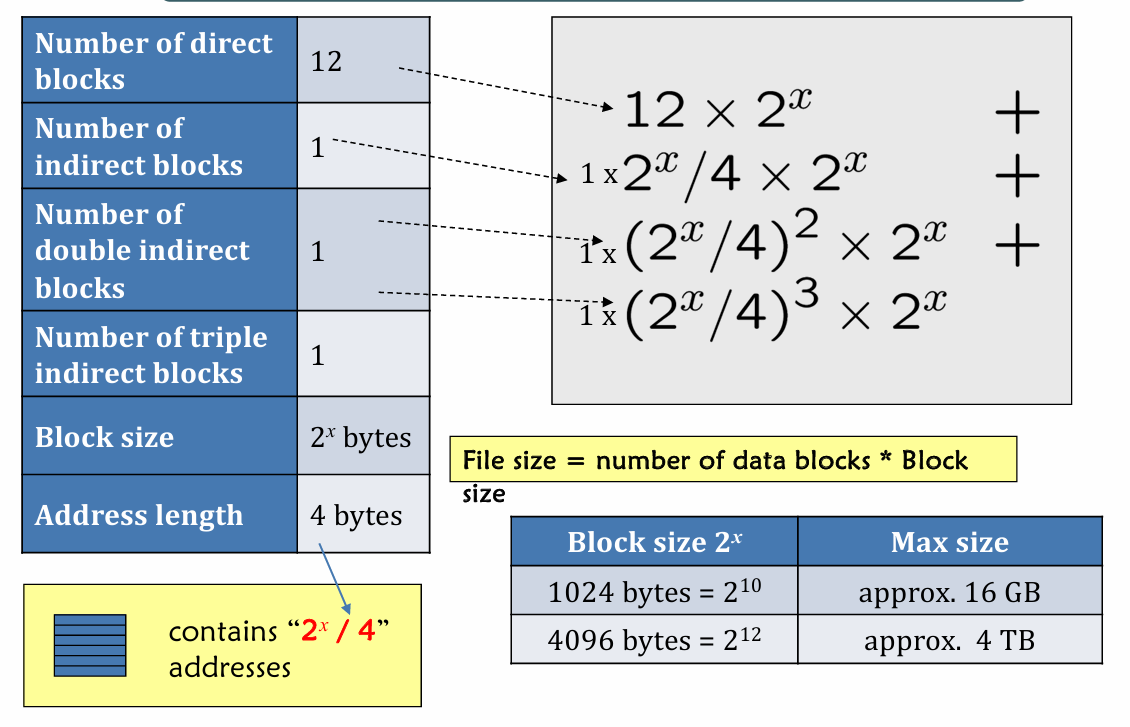

Also see how to calculate File size based on given info.

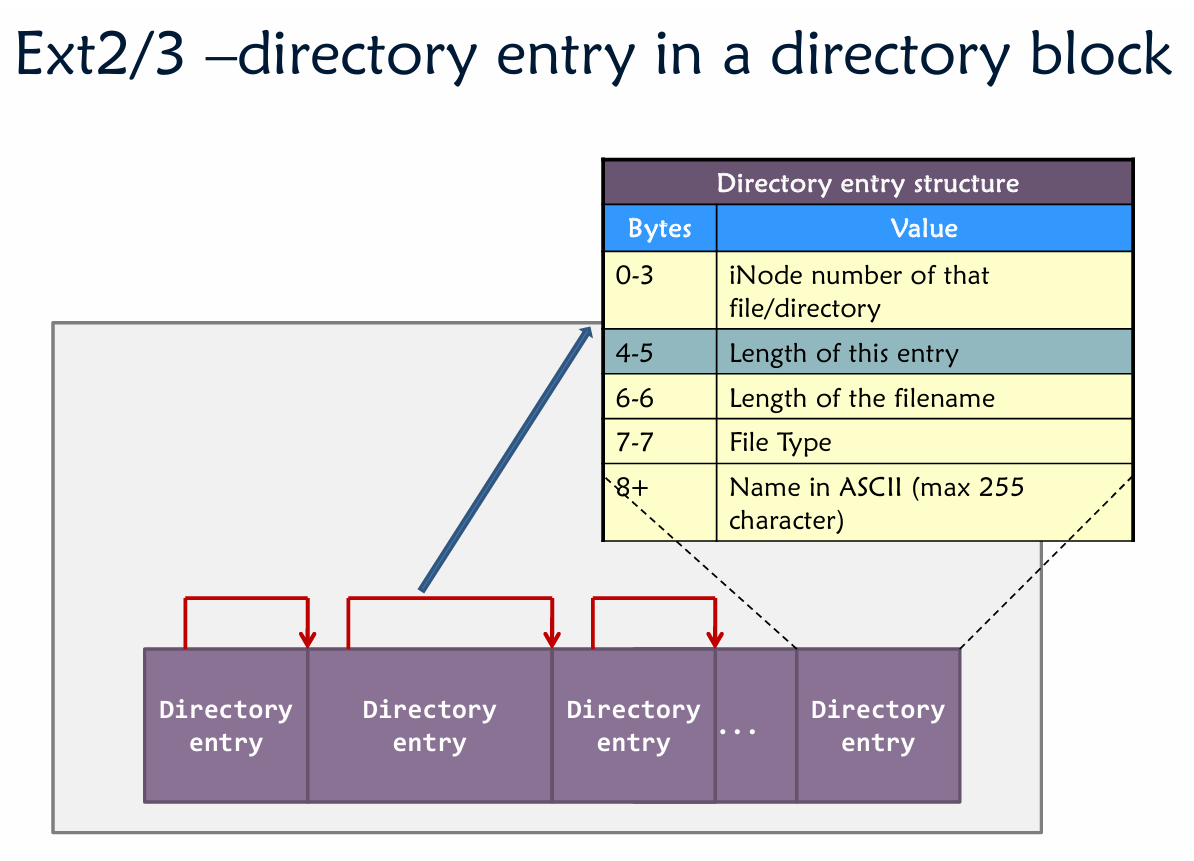

Ext 2 / 3 / 4

The latest default FS for Linux distribution is the Fourth Extended File System, Ext4 for short.

Ext 2/3

- For Ext 2/3:

- Block size: 1024, 2048, 4096 bytes

- Block address size: 4 bytes $\Rightarrow$ # of block addresses $=2^{32}$

- So their File System Size = 4 TB, 8 TB and 16 TB

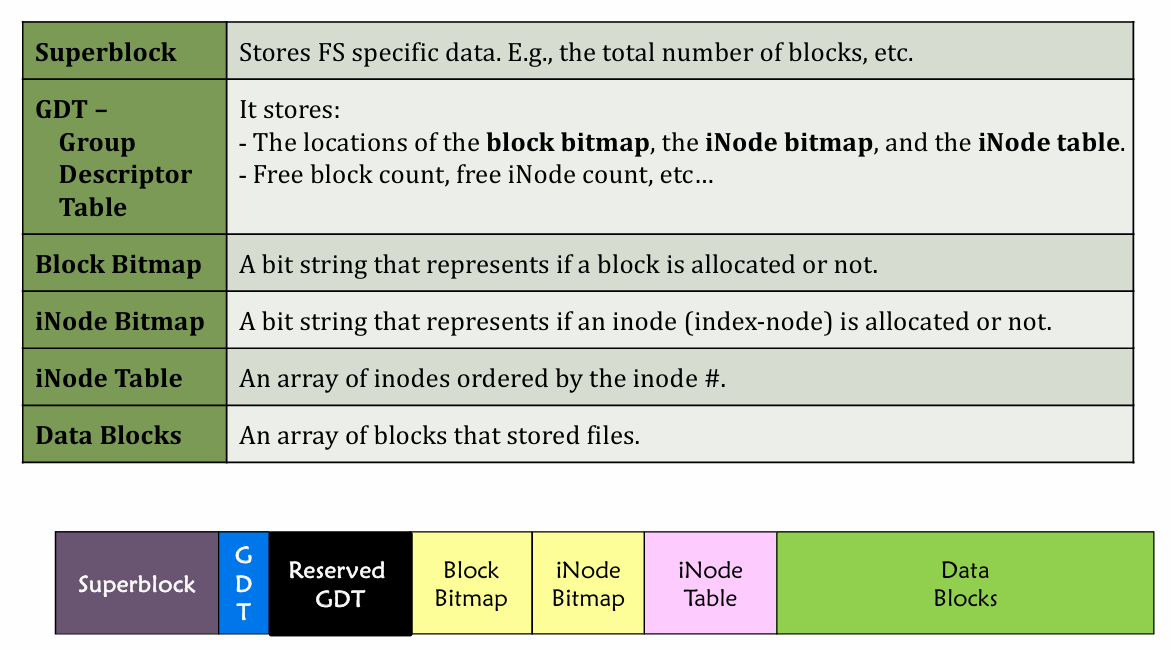

- Structure

- divided into block groups (each block group like this 👇)

- Block Bitmap tells which data block is allocated

- iNode Bitmap tells if an iNode is allocated

|

|

File deletion is just an update of the “entry length” of the previous entry.

Hard & Soft link

| Properties | Hard Link | Symbolic Link |

|---|---|---|

| Creation | Link to the same iNode (may have different file name) | create a new iNode |

| when link is deleted | Reference counter decrease(target delete at 0) | Target unchanged |

| when target is moved | remain valid | link invalid |

| Relative path | N/A | less than 60 characters(12 direct block and 3 indirect) is allowed |

| Crossing filesystem boundaries | Not supported(target must be on same filesystem) | Supported |

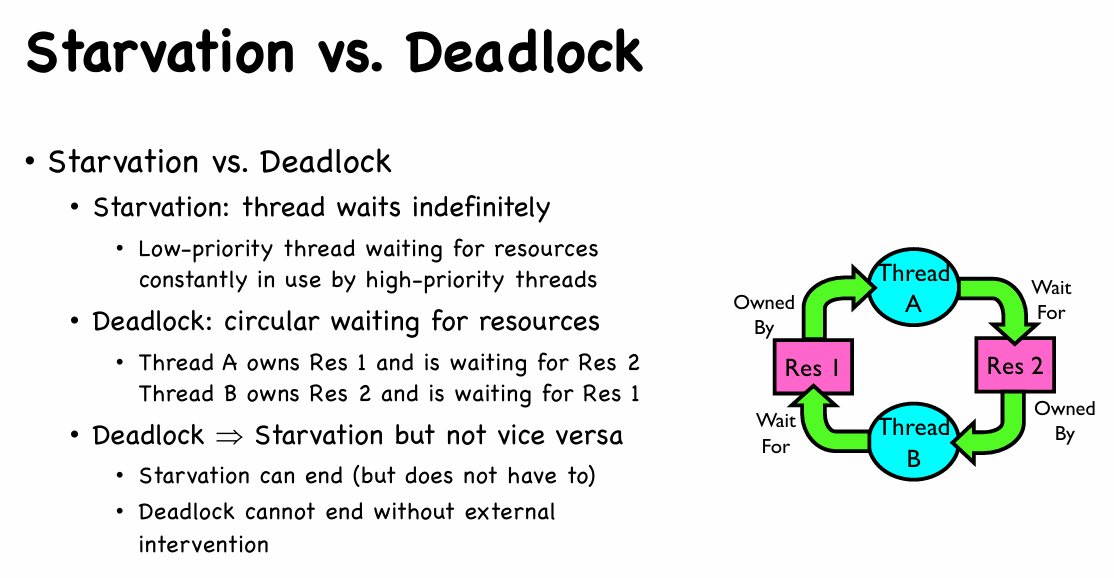

Lec13. Deadlock

Outline

Deadlock Basic

- 4 Requirements for Deadlock

- Mutual exclusion

- Only one thread at a time can use a resource.

- Hold and wait

- Thread holding at least one resource is waiting to acquire additional resources held by other threads

- No preemption

- Resources are released only voluntarily by the thread holding the resource, after thread is finished with it

- Circular wait

- There exists a set ${T_1, …, T_n }$ of waiting threads

- $T_1$ is waiting for a resource that is held by $T_2$

- $T_2$ is waiting for a resource that is held by $T_3$

- …

- $T_n$ is waiting for a resource that is held by $T_1$

- Mutual exclusion

Two ways to handle deadlock

Of course you can directly ignore it (like UNIX), but we are going to talk about 2 methods which truly handle it.

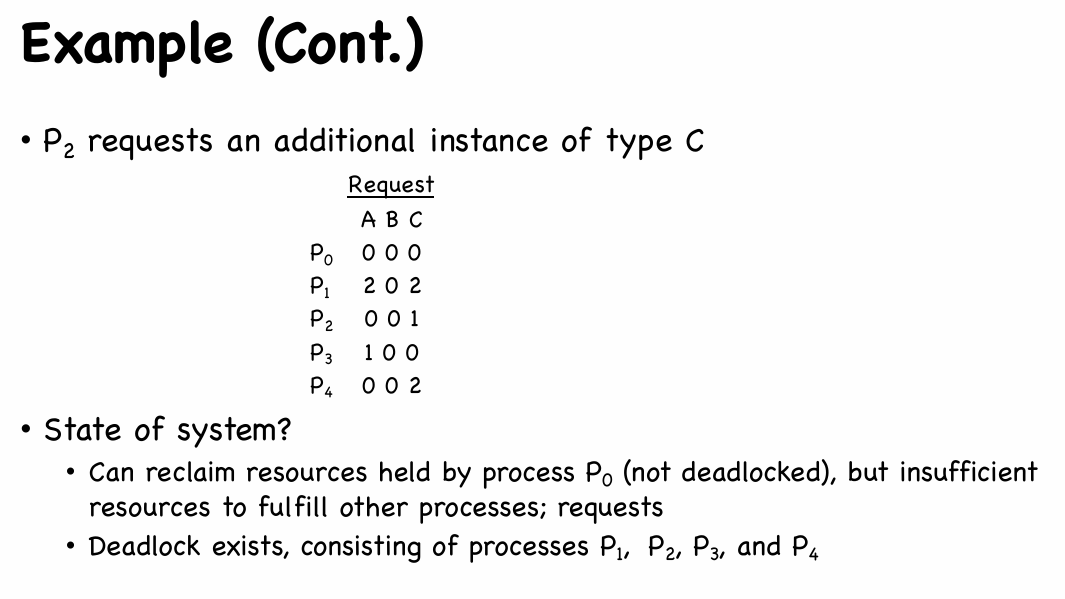

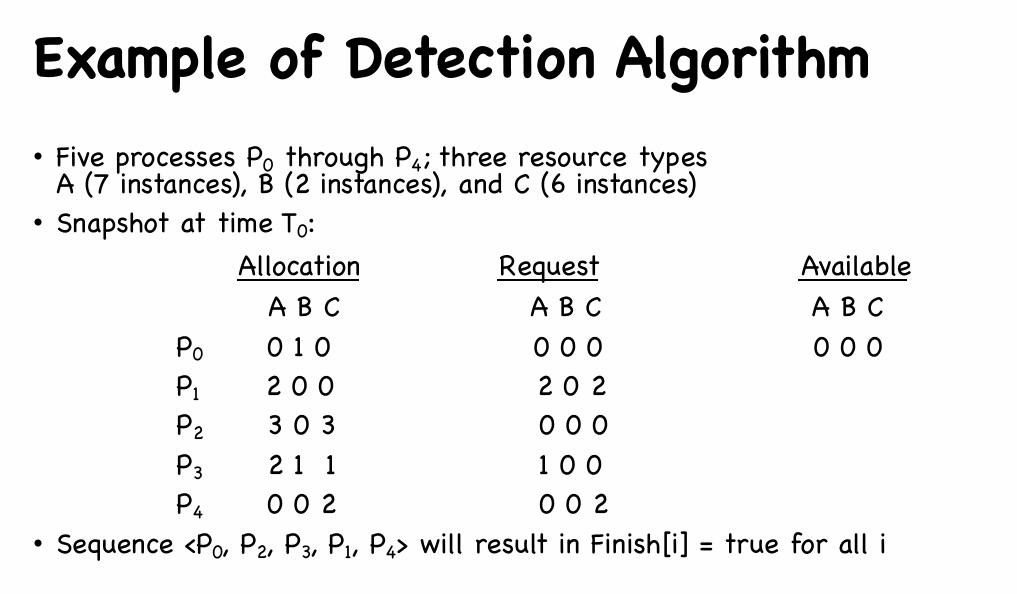

Deadlock detection with Resource Allocation Graphs

- If there is only one type of resource, go searching for cycle.

- If there are multiple types of resource, we have to firstly represent the resource:

- Available: A vector of length $m$ indicates the number of available resources of each type.

- Allocation: An $n \times m$ matrix defines the number of resources of each type currently allocated to each process.

- Request: An $n \times m$ matrix indicates the current request of each process. If Request $[i_j] = k$, then process $P_i$ is requesting $k$ more instances of resource type $R_j$. (Request-based)

Suppose m and n are number of resources and processes

1 | /* Step 1 */ |

|

|

Explanation: 经过进程 0,0 完成并释放一个资源 B,然而其他进程都无法得到相应资源,进入死锁

What if Deadlock Detected?

- Terminate process, force it to give up resources

- Shoot a dining philosopher !?

- But, not always possible

- Preempt resources without killing off process

- Take away resources from process temporarily

- Does not always fit with semantics of computation

- Roll back actions of deadlocked process

- Common technique in databases (transactions)

- Of course, deadlock may happen once again

Deadlock Prevention

Try to ensure at least one of the requirements of deadlock cannot hold

- Remove “Mutual Exclusion” ? impossible for non-sharable resource.

- Remove “Hold and Wait” ? low resource utilization or starvation

- Remove “Preemption” ?

- If a process that is holding some resources requests another resource that cannot be immediately allocated to it, then all resources currently being held are released 👉 may cause starvation

- Process will be restarted only when it can regain its old resources, as well as the new ones that it is requesting

- Remove “Circular Wait”

- impose a total ordering of all resource types, and require that each process requests resources in an increasing order of enumeration: $R= { R_1, R_2, \cdots , R_m }$

- One to one function $F:R\to N$

- If a process request a resource $R_i$, it can request another resource $R_j$ if and only if $F(R_i) \lt F(R_j)$

- Or, it must first release all resource $R_i$ such that $F(R_i) \ge F(R_j)$

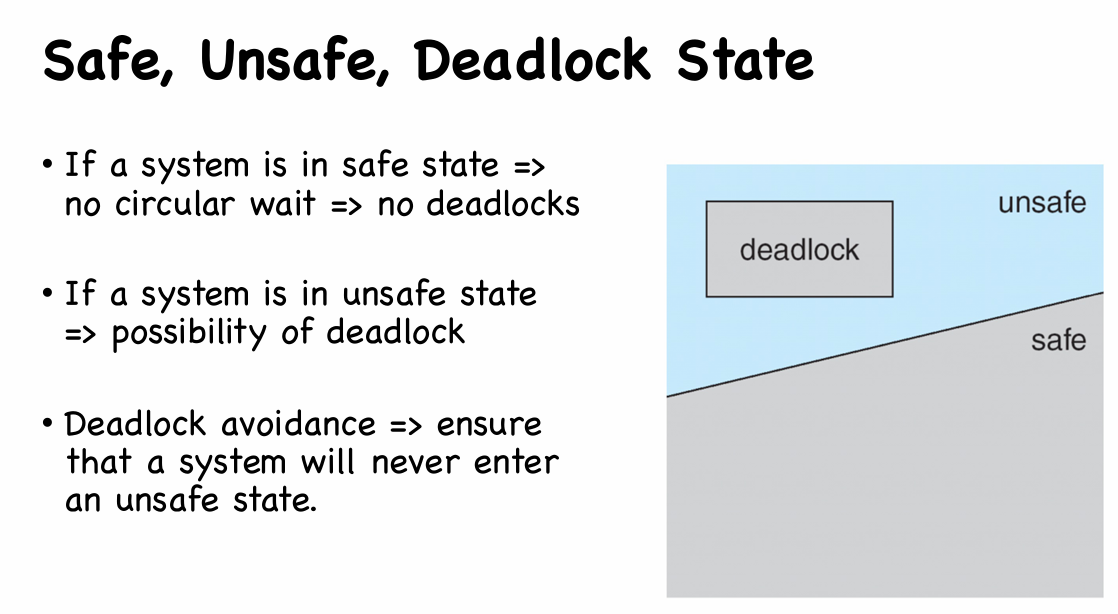

Some concept go first

- Deadlock Avoidance

- The deadlock-avoidance algorithm dynamically examines the resource-allocation state to ensure that there can never be a circular-wait condition

- Resource-allocation state is defined by the number of available and allocated resources, and the maximum demands of the processes

- Safe State

- System is in safe state if there exists a sequence $<P_1, P_2, \cdots , P_n>$ of ALL the processes in the systems such that for each $P_i$, the resources that $P_i$ can still request can be satisfied by currently available resources + resources held by all the $P_j$, with $j < i$

Bankerʼs Algorithm

Idea

- Multiple instances of each resource type

- Each process must a priori claim maximum use

- When a process requests a resource it may have to wait

- When a process gets all its resources it must return them in a finite amount of time

Setting

- Available: Vector of length m.

- Max: $n \times m$ matrix. (

Max[i, j] = krepresent process i can request at most k instances of resource j) - Allocation: $n \times m$ matrix.

- Need: $n \times m$ matrix.

Need[i,j] = Max[i,j] - Alloc[i,j]

Pseudo code

1 | /* Check safe function */ |

Resource-Request Algorithm

1 | /* Request Resource of Process[i] */ |

Lec14. Security and Protection

Outline

- Access Matrix

- Security

- Cryptography

Access Matrix

Principles of Protection

- Programs, users and systems should be given just enough privileges to perform their tasks

- Limits damage if entity has a bug, gets abused

- Can be static (during life of system, during life of process)

- Or dynamic (changed by process as needed)

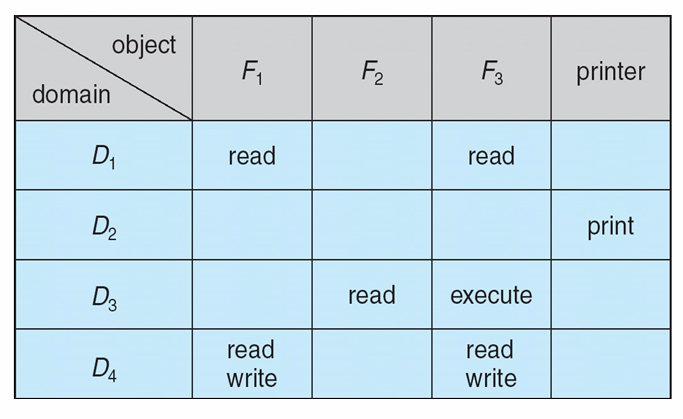

Access Matrix

- View protection as a matrix (access matrix)

- Rows represent domains (e.g. users or processes)

- Columns represent objects

Access(i, j)is the set of operations that a process executing in Domain i can invoke on Object j (as the following pic shown)

- Access matrix design separates mechanism from policy

- Mechanism

- Operating system provides access-matrix + rules

- It ensures that the matrix is only manipulated by authorized agents and that rules are strictly enforced

- Policy

- User dictates policy

- Who can access what object and in what mode

- User who creates object can define access column for that object.

- Mechanism

Implementation of Access Matrix

Option 1 —— Global table

- Store ordered triples

<domain, object, rights-set>in table - Problems

- too large to fit in main memory

- difficult to group objects (consider an object that all domains can read)

Option 2 —— Access-control lists for objects

- per-object list consists of ordered pairs

<domain, rights-set>defining all domains with non-empty set of access rights for the object

Option 3 —— Capability list for domains

- Domain based lists

- Capability list for domain is list of objects together with operations allows on them

- Object represented by its name or address, called a capability.

Last Solution: Combine Access-control lists and Capability lists.

Security

- Concept

- Threat is potential security violation

- Breach of confidentiality: Unauthorized reading of data